Come see the birthplace of Georgia’s largest family-run textile empire!

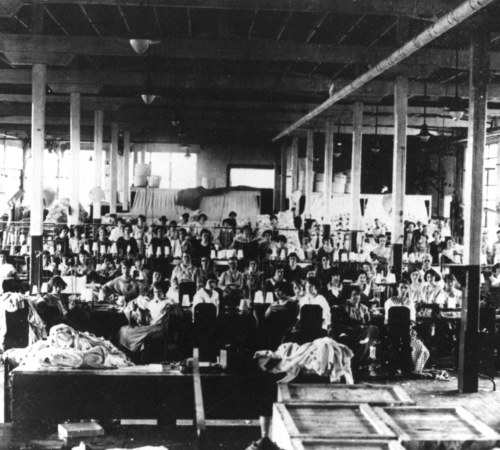

West Point was home to one of the largest locally-owned companies to come out of West Georgia. Formed in the aftermath of the Civil War, the mills which became West Point Manufacturing provided jobs through the hard years of Reconstruction. West Point Manufacturing was formed circa 1881 and expanded steadily under the leadership of the Lanier family over the next 100 years, consolidating their stakes in the Chattahoochee River valley, the west Georgian, southeastern, and national markets in succession. The company collapsed after a hostile takeover shook it to its core in 1989, leading to an exodus of top executives. Today, many of the West Point Manufacturing’s brands are produced by a successor company, WestPoint Homes.

Visit

Things To Do

- West Point Depot, 500 3rd Avenue: The building dates back to 1887, and was at one time the freight transfer building for Alabama and Georgia railroads. Now, it is a visitor center and museum. Their hours of operation are Monday through Friday 9:00 am – 4:00 pm and Saturday 10:00 am – 2:00 pm.

- Riverview Dam, 105 Lower Street, Valley Alabama: This site is a public area where the original dam which provided power for the Riverdale Cotton Mill is located. Visitors can wade into the Chattahoochee River to examine the dam and view the site of the Riverdale mill.

Places To See

- Fairfax Mill and Mill Village, 436 Boulevard: The village is centered on a main street that loops from Highway 29 towards the site of the mill before turning back to Highway 29. This was the final village built and designed by West Point Manufacturing. 200 homes were built here between 1915 and 1919, with a further 200 or so built by 1936 across Highway 29 in an area called New Town. A handful of the remaining homes on Johnson and Peterson streets were part of the “colored village” which housed African American employees during the segregation period. These employees worked mostly in construction, at the West Point Utilization plant, or as menial laborers. Their homes are notably smaller and farther away from the mill than homes built for white employees. The company built several amenities during this time including a swimming pool, tennis courts, gym, boarding house, and a baseball field, Crestview Ballpark, which still stands. Crestview Field, as it is now known, can be found at 198 W. Sears Street.

- Shawmut Mill and Mill Village, 2302 34th Street: The majority of the mill has been demolished, but the foundation, a small portion of the original facade, and the central tower can all be viewed at 2302 34th Street in Valley, Alabama. However, the mill village is intact. This was the first comprehensively planned mill village built by West Point Manufacturing. Shawmut was designed as part of the City Beautiful movement of the 1900s which included professional planning, coordination of architecture and landscaping, and the prominent placement of public buildings. The layout of the village is centered on a North-South axis and spreads out of a circle situated directly in front of the mill. 8 residential streets radiate out from the central circle to the boundary of the formal plan, which forms a rough hexagon. The Chattahoochee Valley Railroad forms the eastern edge of the hexagon. Public buildings along the central circle included a school, three churches, a library, an auditorium, a movie theater, and the “Lower Stores” shopping center. The “Upper Stores” shopping center was located near the superintendent’s house further up the main boulevard. The village also boasted a modern hotel, cafeteria, and sporting facilities such as tennis courts and a baseball park.

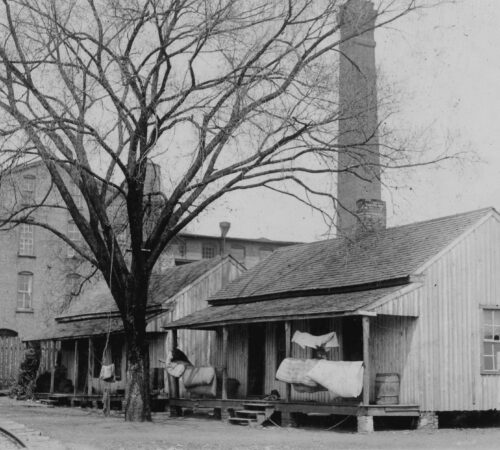

- Riverdale Mill Site and Riverview Mill Village, 53 Middle Street: The site of the former Alabama-Georgia Manufacturing Company is still partially intact, although demolition has been in process since before 2017. Visitors can drive through the mill village, which is a good example of earlier unplanned “mill hill” developments that sprung up around textile factories.

- Langdale Mill and Mill Village, 6000 20th Avenue: The earliest portions of Langdale Mill date back to the 1880s and the beginning of West Point Manufacturing. While much of the mill has been demolished, the original main mill still stands as of May 2020. Langdale’s mill village is a good example of early textile “mill hill” villages, which were rather disorganized clusters of duplex houses constructed near the mill. These early homes were gradually upgraded by the company and were joined by the addition of 150 single-family frame bungalows between 1920-1936. Village life was augmented by company-owned schools, churches, gymnasiums, a baseball field, pools, and a masonic lodge.

- Lanett Mill and Mill Village, 600 US-29: This is the site of the former Lanett Cotton Mills. While the mill itself has been demolished, the barracks-style mill village still stands. Much of the original houses still exist in the area bounded by 1st street, 10th Street, 4th Street, and Highway 29. This area was directly across from the mill.

History

Explore this community’s history via the drop-down sections below!

Charter Trail Members

Resources to Explore

Click on the following links to learn more about this region.

- Facts for Kids

- Digital Library of Georgia

- Georgia Archives Virtual Vault

- Georgia Historical Society

- Troup County, New Georgia Encyclopedia

Back to Community List

Email the Trail at wgtht@westga.edu or visit our Contact Us page for more information.