Author: Jarrett Craft

Introduction

Dellinger Inc. was a chenille bedspread and custom carpet producer in Rome, Georgia. Founded by Walter Edwin Dellinger and his wife Callie in the mid-1930s, the company was passed down from generation to generation for 60 years until it finally went out of business in the early 1990s. The company had a plant which took up roughly a whole block on the outskirts of town. The plant became a sophisticated operation with highly skilled technicians and designers working alongside highly proficient employees who filled more traditional roles along the production line. During Walter’s lifetime, the company made chenille bedspreads and tufted carpets from cotton. His successor and son-in-law, Edward Dowd, switched to the wool and nylon custom carpets that the company produced until it closed.

Those are the bare facts. But there is a lot more to Dellinger Inc. than meets the eye. The company possessed a community and culture that was entirely its own, a culture which was defined by close relationships between the Dellinger family and their employees. To shed light on this culture, the truest legacy of Dellinger Inc., we must start at the beginning with Walter Edwin Dellinger.

Humble Beginnings: Walter and Callie Dellinger’s Early Lives

Walter Edwin Dellinger was born into a large family in Bartow County, Georgia, in either 1885, or 1887 depending on the source. His father, Washington Dellinger, appears to have been a sharecropper, meaning that he shared the profits from the harvest (usually cotton) with the landowner in lieu of rent. Sharecroppers were almost always trapped in a brutal debt cycle designed to keep them poor. These families often moved from farm to farm working as a family; in some cases they would swap back and forth between the farm and a cotton mill.

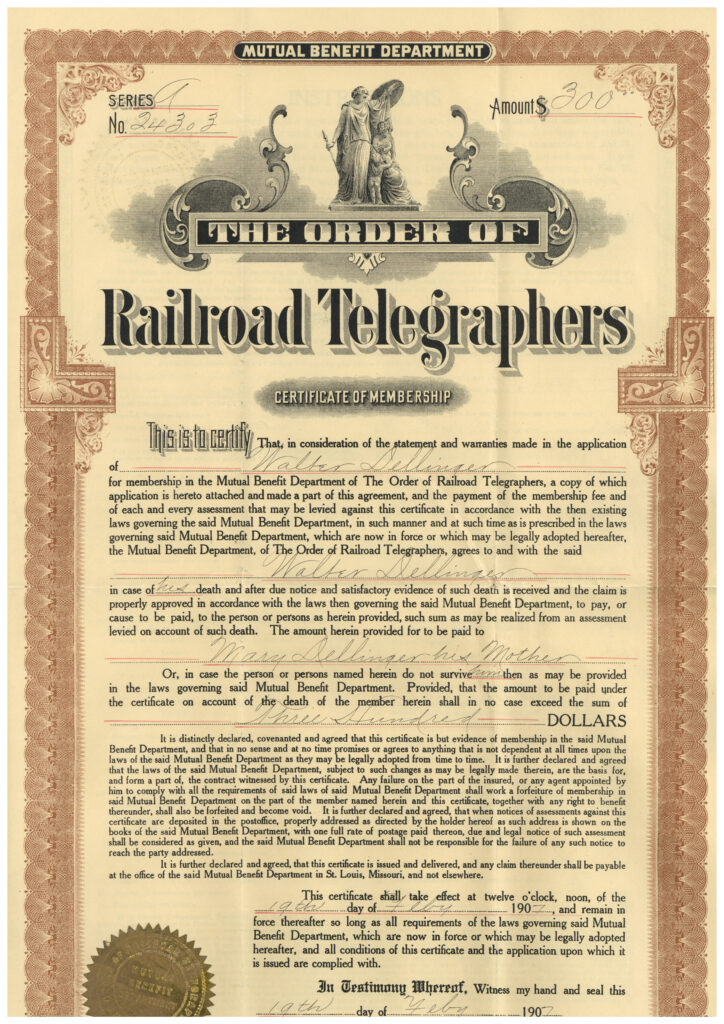

With that in mind, Walter’s family appears to have been fortunate because they did not move too often; they lived at the same address in Sonoraville in Gordon County between 1900 and 1910. Walter managed to attend school through the 7th grade while working on the farm. In 1904, just before his 20th birthday, Walter received certification from the Gordon County Schools to teach 3rd grade. This was a fitting career for a man who would often write poetry for family members and eventually served as a correspondent for the Atlanta Journal Constitution on occasion. However, it did not last. By 1907, he had begun a fairly lucrative career as a railroad telegrapher and depot agent.

While working for the railroad, Walter met and married Callie Echols. Family tradition holds that Walter was an “entrepreneur,” meaning that he was always finding odd ways to make money on the side. Between those various side jobs and his career with the railroad, Walter provided a comfortable life for Callie as they built their family. Callie gave birth to their oldest daughter Doris in 1915. Three years later Doris became a big sister to Madge. Doris claimed that Madge was Callie’s favorite, while she herself commanded Walter’s affection. With that said, both daughters were doted upon by their parents and had comfortable childhoods, especially compared to that of their father.

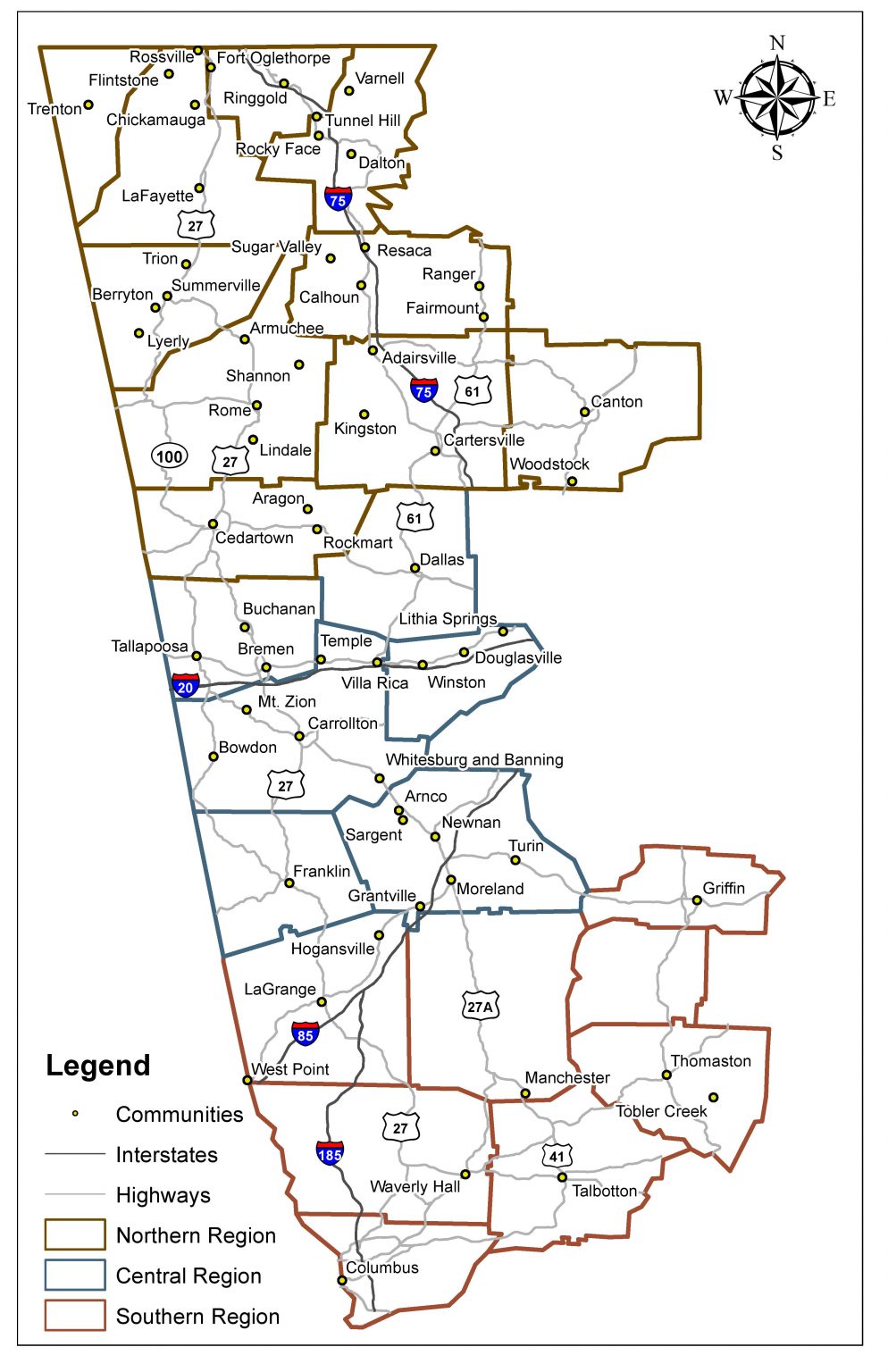

A New Chapter: Dellinger Spread Company

By 1930 Walter had moved the family to Dalton, Georgia. Walter, now aged 44, had done well for himself. He had a stable job, still working as a freight agent for the railroad, during the worst years of the Great Depression. The family owned their own home valued at $10,000 ($165,622.16 in 2021), and even had their own radio set. Their daughters had educational opportunities that were never available to Walter or Callie. Despite the dire circumstances being experienced by the nation, things were going well for the Dellingers.

Dalton was the epicenter of the chenille tufted bedspread, robe, and rug industry. What started as a cottage industry selling bedspreads to tourists driving down Old Highway 41 to the beaches of Florida had become a fully-industrialized commercial enterprise for many entrepreneurs by the 1930s. These local businesses took advantage of the international fad of chenille products to sell beyond their local markets and meet demand in the great northeastern cities, with many close ties to New York in particular. There was also plenty of demand across the Midwest and as far away as Europe.

Chenille in the 1930s was a pioneering business within the textile industry. It was high risk, but it did provide a chance for small businesses to take a piece of the pie. In an industry that had been dominated by large textile corporations for years, many rightly predicted that chenille production would be a way to grab a foothold in the textile market. Walter Dellinger, always the entrepreneur, must have realized this historic opportunity while living in Dalton, the chenille capital of the world. However, Dalton was already saturated with the chenille industry, so it would be tough to prise employees away from established companies. If Walter and Callie were to start a chenille business, they needed a place relatively untouched by the chenille boom in Dalton and Calhoun. With that in mind, in 1934 Walter retired from the railroad, sold his home in Dalton, and moved to Rome, Georgia to start the next chapter of his life: Dellinger Spread Company.

An Old Fashioned Startup

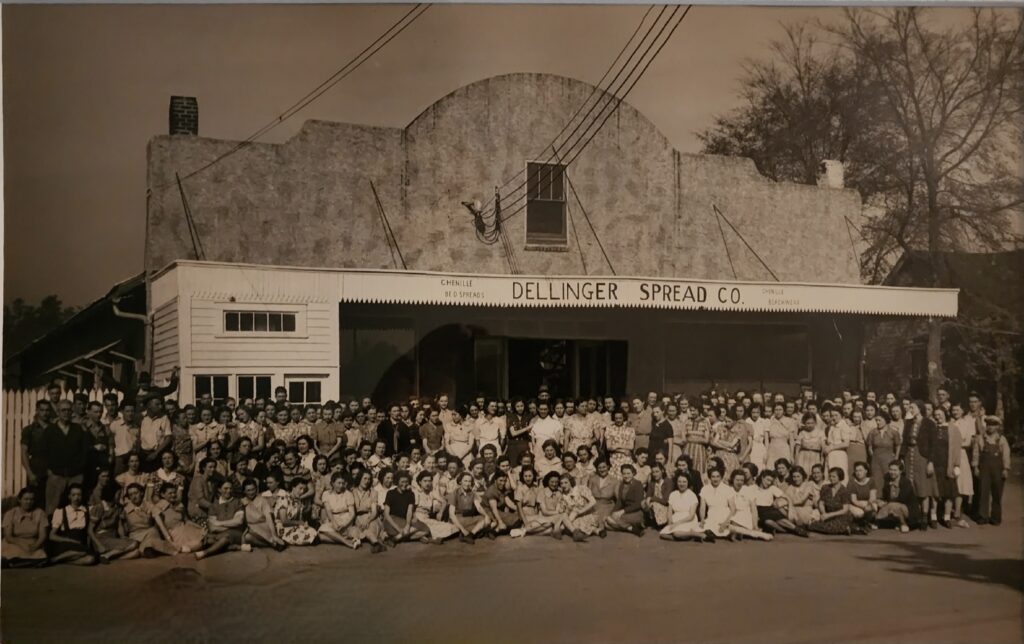

Walter and Callie Dellinger started Dellinger Spread Company with little if any experience in the chenille business. They purchased second-hand equipment and hired a largely female workforce from the surrounding countryside and town. It is unclear how much experience these employees had. Many of these women would not have been familiar or comfortable with work on an assembly line. Bedspread manufacturers in Dalton and Calhoun tackled this issue by providing the raw materials for tufters to work in their homes. When the tufter finished the bedspread, the manufacturers would collect the bedspread and bring it back to their plant to apply the final touches and designs. This allowed women to work from their homes where they could still assist in farm labor, chores, and child rearing while also supplementing the family’s income.

Walter Dellinger used a similar method in the early days of Dellinger Spread Company. He started off with a converted garage as his collection and distribution center. The Dellingers had local women tuft the bedspreads in their homes, and paid them by each completed item rather than an hourly wage. The Dellingers would pick up the bedspreads and apply the finishing touches in their plant, before packaging and shipping them to clients across the United States. Walter and Callie quickly built a network of sales agents in the major cities of the North and Midwest. Before long, it became prudent to have employees work on site in the plant.

Company tradition tells that the first addition to the original plant was a dye house built in the 1940s, used for dyeing skeins of yarn purchased from suppliers. Payroll records from September 1938 to February 1939 indicate that at least some employees worked on site. When they missed their shift, the bookkeeper scribbled “not here” next to the employee’s name. The payrolls show that there was a corps of regular employees who worked day in and day out. They were supplemented by irregular employees when demand picked up or a regular employee missed a shift. It is unclear if these employees worked in shifts, and if so, how many worked on a shift. What can be said for certain is that Dellinger Spread Company had quickly built a workforce to rival established cotton mills in the area.

Dixie-Dell on the National Market

The Dellingers were able to expand their company with incredible rapidity. This growth was based on their ability to fill orders placed in major commercial centers across the nation. In New York, Walter’s friend Norman Roemer served as a great marketing agent. Earl Barton traveled the Midwest gathering orders for the company as well. But to truly establish themselves, it became clear that Dellinger Spread Company would need a signature product. But finding that trademark item was easier said than done.

Indeed, much of the company’s early days seems to have been based on trial and error. One Dellinger granddaughter remembers “Smokey the Bear” bath mats as one of Dellinger Spread Company’s earlier product lines from the 1940s. According to her, they must not have sold well because dozens of them remained in the family’s basement well into the following decade. But the Dellingers struck gold when they trademarked the Dixie-Dell brand. By the early 1940s it had become their calling card in the textile industry, a brand that they proudly emblazoned on company letterheads. In 1942 the company had selling agencies in New York, Pittsburgh, Boston, Chicago, and Kansas City.

Part of the national appeal of the tufted bedspread industry came from the fact that the employees who made it were of “pure Anglo-Saxon stock.” The 1930s saw bigotry, xenophobia, and racism reach a high in many western countries, the United States included. The previous decades had seen waves of Chinese, Eastern European, Italian, Irish, and German immigrants flood into the United States, and many were concerned about the dilution of Anglo-Saxon culture in the country. Georgia-based manufacturers of chenille bedspreads took advantage of this wave of anti-immigrant sentiment to emphasize that their employees were “untainted” by the influx of new cultures. The Dellingers were no exception, as the top of their 1940s company letterhead read “Home-made, Rome-made by the Highlanders of Georgia.” The message was clear to Dellinger Spread Company’s customers: Dellinger products were not made by Asians, Eastern Europeans, Jews, or African Americans.

Separate and Unequal: African Americans at Dellinger Inc.

Dellinger Spread Company prided itself on the opportunity for upward social mobility and financial independence that it provided for its employees. The company employed many single mothers over the years, empowering women to leave and avoid abusive relationships on which they may have been otherwise financially dependent. As indicated by the company letterhead mentioned above, the Dellingers employed white women primarily. Dellinger Spread Company, as a general rule, did not hire African Americans; who therefore missed out on the social and economic benefits that the company provided.

This, of course, could be chalked up in part to Jim Crow segregation laws and industry-wide labor practices which were pervasive at the time. Southern textile industrialists had been claiming since the 1880s that African Americans were mentally unfit to work any of the machinery in their factories. Many believed Their racist views held that African Americans were only capable of doing the most menial, dirty, and backbreaking jobs in the mill. There are dozens of accounts of white employees walking off the job when management tried to promote an African American to a position that they felt should be reserved for white people. The Dellingers may not have felt strongly about enforcing these racist industry standards, but they certainly did little to challenge them.

The result was that, whether intentional or not, Dellinger Spread Company was a segregated workplace. If African Americans worked at the plant at all, they only did the most unpleasant or lowest paying jobs that the company had to offer, as would have happened at other textile industries in the region. At various points over the course of Dellinger’s 50 plus years of history, African Americans may have worked in more menial positions in the shipping department or as janitors. At any rate, there was no place for them in the company potlucks and parties. They missed out on the Christmas gifts from management. They were not allowed to make an impact or even take part in the company’s culture that shaped the lives of so many. More importantly, African Americans did not have the opportunity to use Dellinger Spread Company as a means for financial mobility and independence. At Dellinger Spread Company, and the wider textile industry, African Americans did not receive the benefits of industrialization.

A Company Family: Paternalism and Company Culture under Walter Dellinger

The Dellinger family worked hard to create a close knit environment amongst their employees. Towards that end, they often hired several members of the same family. Dellinger family members made sure to send notes to employees who had fallen ill or who had a death in the family. They threw company Christmas parties and asked their grandchildren to distribute gifts to the employees. Taking a cue from more established textile companies, such as Callaway Mills, the Dellingers distributed turkeys or hams to the employees to serve as the mainstays of their Christmas dinners.

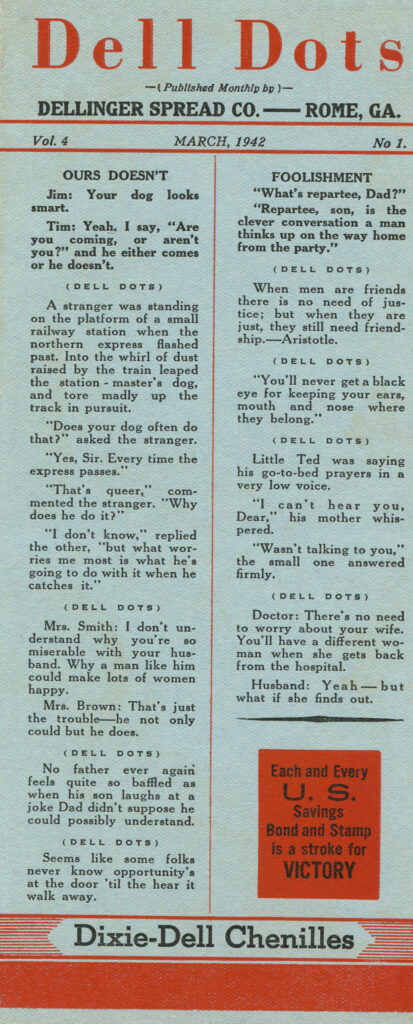

The Dellingers saw their company not only as a way to make money, but also to help improve the lives of their employees. As part of that mission, Walter hoped to provide recreation for his employees. He created a series of company publications known as “Dell Dots”, which offered casual reading material to his employees. It seems that Walter started the Dell Dots as early as 1942, perhaps in an attempt to lift spirits during the war years. He gathered what must have been his favorite jokes from the various publications to which he subscribed. The result was a compilation of corny quips and exhortations to buy war bonds. He continued to produce Dell Dots into the 1960s.

Regardless of whether the Dell Dots were well received or not, the Dellinger family managed to create a strong bond with their employees and earn their employees’ loyalty. The countless company potluck dinners, Christmas gifts, and personal touches had done the trick. Although injuries were not common, it was not unheard of for employees to suffer broken toes from being crushed by loads of heavy carpet, for needles and punch guns to create puncture wounds, and for cuts and sore heads to result from collisions with the machinery. One woman even lost an arm to the out-dated machinery, but refused to sue. Despite the occasional carnage, union organizers made no headway with the employees of Dellinger Inc.

The New Generation: Edward Dowd Enters the Fold

Doris Dellinger married Edward Dowd during World War II. Edward and Doris settled in Rome after the war and Edward took on a responsible position in the company. Walter often sent Edward to make visits to the company’s representatives in the west and Midwest so that Edward and Doris’ family vacations could be covered by the company. Edward joined Dellinger Spread Company during a period of change. Walter got advice from his long time sales agent, Earl Barton, to switch from tufted bedspreads to carpet manufacturing, a change occurring throughout the industry at the time. This transition resulted in the company rebranding as Dellinger Inc.

Although the company continued to produce tufted bedspreads, chenille robes, and bathmats throughout the 1950s, they began to invest more and more in carpet production. At the beginning of the decade, the company advertised their traditional chenille products in textile sales directories. By the end of the decade, they had invested heavily in a brand new carpet production facility. This gave Dellinger Inc. the ability to manufacture custom carpets made not only of cotton, but also of wool, nylon, and viscose (a synthetically produced silk substitute). The company’s 1957 sales directory entry duly advertised the company’s ability to produce custom carpets.

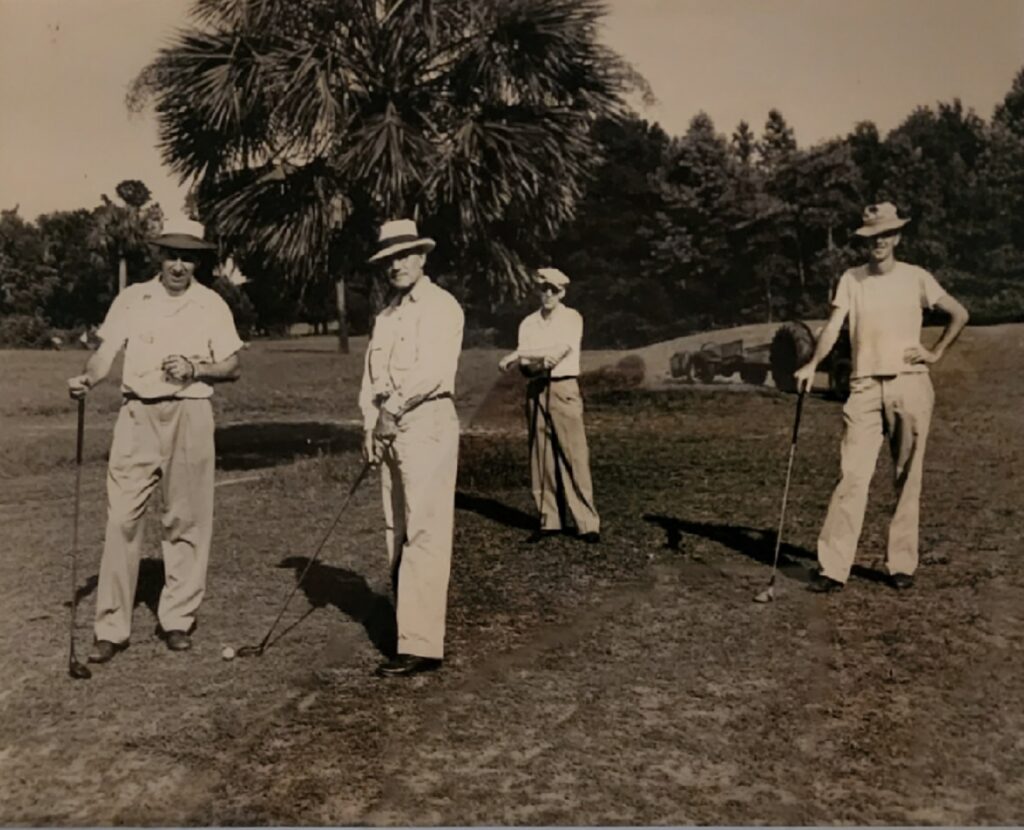

Edward Dowd cut his teeth and learned the industry during this time of transition at Dellinger Inc. During this period, the company employed some 200 operatives, making the company a driving force in the community. Dellinger Inc. was at its pinnacle, but the transition into custom carpet brought uncertainty. Edward undoubtedly drew his own conclusions on how to keep the plant viable for years to come and surely was excited to have the opportunity to implement them. After many years as the understudy during the company’s golden years, Edward got his chance in 1964 when Walter Dellinger passed away.

A New Era: Edward Dowd’s Tenure at Dellinger Inc.

After Walter’s death in 1964, Edward Dowd took control of the company’s day-to-day operations. While all major changes had to be approved by his wife, mother-in-law, and sister-in-law, Edward moved the company in the direction that he saw fit. His legacy would be a continued specialization in custom carpets. However, certain patterns never altered as power changed hands. Walter and Callie had drilled their values well into their family. As far as the Dellinger family was concerned, the company was a means to support the community and lift employees out of poverty just as much as it was a livelihood for themselves. Employees were to be treated with gratitude and respect by the whole family. Edward could be more stern than Walter, as he tolerated zero “gossip or back talk,” but his goal was always to ensure that the Dellinger grandchildren treated Dellinger Inc.’s employees well. When Edward converted to the Baptist faith in 1973, he began leading a morning Bible study at the plant before work. True to form, he worried that his employees would feel pressured to attend because he was the boss.

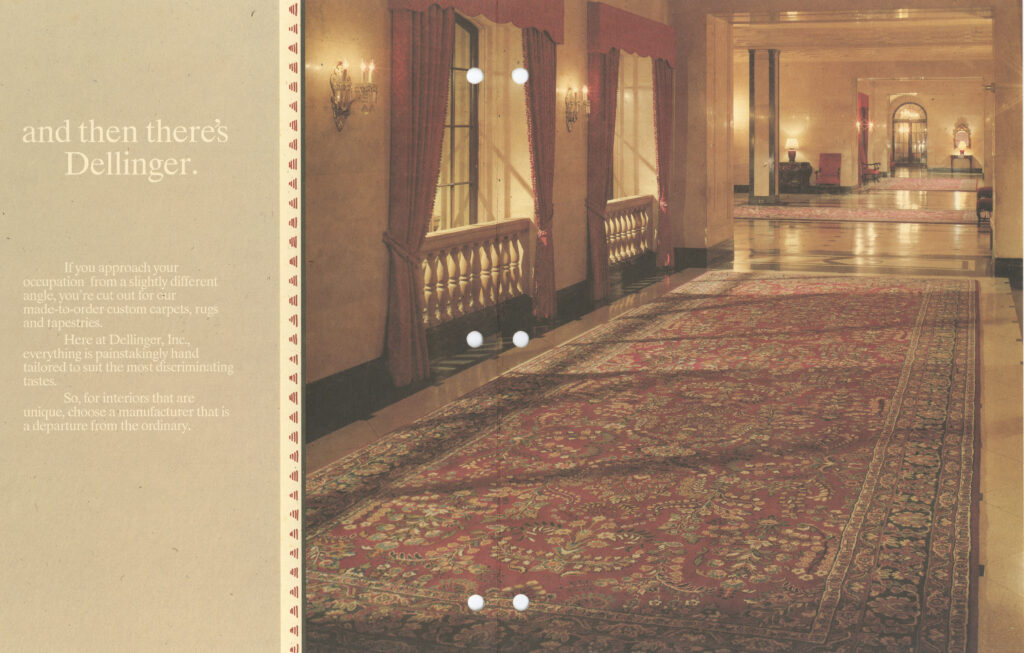

Under Edward, the company began to manufacture carpet using high-quality wool imported from New Zealand. He supervised the construction of a larger and more modern dye house as well as a filtration and softening room. Together this allowed for the company to establish a color lab to precisely match swaths of cloth or color samples sent in by customers. As the company began to lean further into the high-end custom designed carpet sector, it seemed that they had finally found a niche to dominate within the textile industry.

From the 1960s to the 1980s, Dellinger Inc. did some impressive business. Their workers, already skilled, came to be masters of their craft. Employees from the design team and color lab to the tufters and the twisting department all reached exceptional levels of skill. Dellinger great-grandson David Mitchell recalls the production process.

“A carpet was first laid out by using a spur like device to use a purple dye to imprint the design of the carpet. Depending on the level of complexity – it would go to the punch gun and have the design – followed by the colors – and then laid out with the design. This took weeks as you had intricate pieces in the carpet. It would then go back downstairs and be hand carved to the specifications. These were artisans that did this work. The precision was unparalleled and it was always women – never men that did that work. Next it would go to have rubber put on the back of the carpet – again this is a process and took weeks. Finally, it would be wound face out and placed in a tube for shipping.”

David Mitchell, Dellinger Descendent and Employee

Their custom carpets and rugs could be found in corporate offices, ornate hotels, and the homes and estates of wealthy individuals. Dellinger Inc. began dealing with more and more impressive clients, who often required not only increased levels of quality but also larger sizes. Management and employees alike were particularly proud of a massive carpet mural for the Frito-Lay Company’s research center in Texas. Carpets of this size forced the company to invest in a larger finishing and shipping room, where they could lay out the massive carpets for quality control trimmings, final inspections, and packaging. Before this, they had to use the warehouse floor space of a local lumber dealer in order to accommodate larger carpets, such as for hotel dining rooms.

Papering over the Cracks: The Decay of Dellinger Inc.

Dellinger Inc. was not without its problems. Under Edward Dowd, the company had flourished, coming to dominate a niche in the textile industry. The employees had reached the pinnacle of their craft. However, much of the Dellinger family pursued their own lives and interests, rarely taking part in events or management of the company. The equipment did not always meet safety codes, and by the 1980s was not only dangerous but also unreliable. Despite the additions to the plant in the 1960s and 1970s, the majority of the equipment in older portions of the plant had not been updated. Even so, clients demanded higher and higher quality for the prices that Dellinger Inc. offered. As the years passed and the pressure began to bear down, Edward’s often stern demeanor seemed to feel more and more harsh, ultimately creating a brutal cycle.

Edward’s irritation could be taken out on the employees or the clients; threatening the fragile social system at Dellinger Inc.. In order to produce the quality levels desired by their clients at a profit, the company would have to lower or cease dividend payments on their stock, which would certainly raise issues from the extended Dellinger family. Cutting wages would upset the employees, who could already undoubtedly feel the company’s close knit environment straining under the pressure. There must have seemed to not be any way forward without offending one group or another, and potentially bringing the whole company crashing down around them. There was but one person who had all the qualities to keep the Dellinger Inc. machine running: Martin H. “Buddy” Mitchell.

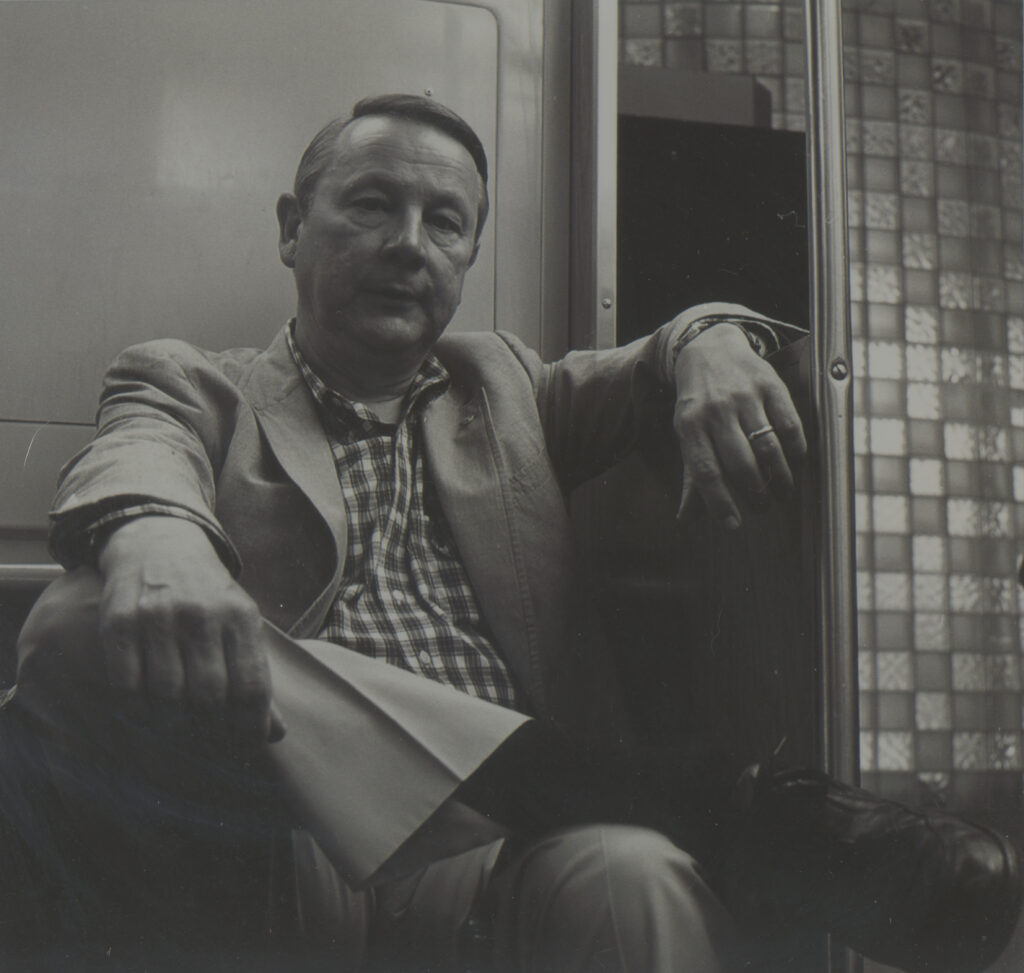

Buddy Mitchell (b.1940) was a native of Rome, Georgia. He met and married Madge’s daughter, Penney Yoakley; so he was a member of the Dellinger family by marriage and his children were Walter and Callie’s great-grandchildren. He could serve as one of the family’s ambassadors at company parties and events. Moreover, he represented the branch of the Dellinger family that had been geographically distant for years, as Madge reared her family in Florida. He was part of the management team at Dellinger Inc., so he was able to help meet the needs of clients that other family members may not have been willing to meet.

Buddy was a bit of a scholar, constantly reading on a variety of topics. He was an active community leader in Rome, serving as a city council member from 1974 to 1991. He was regarded as incredibly polite and considered a gentleman by all who had the chance to work with him. He followed in the footsteps of Walter Dellinger in many ways; even briefly working as a teacher before joining Dellinger Inc, just as Walter had worked as a teacher before working for the railroad. Buddy Mitchell understood the value of the relationship that Dellinger Inc. had built with both their employees and their customers, and he was committed to preserving it. Given the power of the forces at play, maintaining the company became an uphill battle to say the least.

The Silencing and Demise of Dellinger Inc.

The company culture established by Walter and Callie was largely intact when Buddy Mitchell joined in the early 70s. Since the Dellingers had modeled their company culture on the principles of other regional textile companies, Dellinger Inc. was a time capsule with roots as far back as the 1880s. Many employees had worked at Dellinger Inc. for decades, and expected that culture to continue. Therefore, when employees fell ill or had a death in the family, Buddy Mitchell became the Dellinger family ambassador who paid a visit to offer support or condolences.

He attended company potlucks and parties, bringing his children along with him whether they wanted to go or not. If they complained, he simply told them that it was their duty; he was the “management” presence at the event, but they were the “blood” presence that represented the whole Dellinger family. Patterns of respect which had been in place for decades persisted under Buddy’s watch. His son David recalls that one longtime employee prepared a horrendous carrot and raisin salad for the company potlucks, time and time again. As dreadful as the dish was, everybody ate it to respect that employee and her effort. Even though it made David gag, he took one look at his father and knew that he had to eat it, yet again. Although this is a somewhat extreme example, it shows how Buddy Mitchell tended the family-style relationship that Callie and Walter had cultivated with their employees. He made sure that the employees continued to feel valued by the family.

The antiquated company culture was matched by the dilapidated machinery. Buddy’s son David began working at the plant over the summers during his high school and college years, and was a witness to the last years of Dellinger Inc. Of the plant’s machinery during the late 80s and early 90s, he recalls,

“We had a dye house that was literally like a laboratory and the other various departments were all driven by labor – but the equipment was generally tools – that only worked when in the hands of skilled personnel… Eddie Amos was the “Plant Manager” that would fix anything that was broken – and if parts were needed – they could be taken from other equipment and repaired on site. Everything was driven by the hands of the one that helped the equipment and the talent they brought to the piece. Making spools of yarn for the carpet/rugs was LOUD and fast paced. Clipped/Chipped fingers were common until you developed timing and the understanding of the device. You had to cross train to understand this…”

David Mitchell, Dellinger Descendent and Employee

When clients complained about quality issues, complaints that Edward would have considered “picky,” Buddy handled them personally. On one occasion he traveled all the way to an expensive lake house by the shores of Lake Michigan to make corrections on a carpet that the client found unsatisfactory. When machinery broke in the plant, Buddy and Eddie Amos tinkered with them until they worked again. Although he undoubtedly knew that Dellinger Inc. could not carry on indefinitely without serious changes, he made it work. Whether he was conscious of it or not, he poured his heart and soul into preserving Dellinger Inc.’s profitability, company culture, and pay structure.

As the 1980s gave way to the 1990s it became clear that the system was at a breaking point. No longer could Buddy Mitchell alone paper over the cracks. The world was moving forward from the traditional company culture and business structure on which Dellinger Inc. operated. For example, African Americans had become common in most workplaces by this point, but Dellinger continued to hire mostly white women and remained largely unintegrated after the end of segregation. The world was leaving Dellinger Inc. behind, and something had to give. Ultimately, the company lost profitability. Low cost imports from developing countries had closed the gap in terms of quality because much of the plant’s machinery had not been updated in years. Those companies usurped Dellinger Inc.’s position in the custom carpet market, as clients abandoned them in pursuit of lower costs. Dellinger Inc. became unviable and began to collapse.

The Legacy of Buddy Mitchell

For Buddy Mitchell, it must have seemed as if the whole world was ending, and he undoubtedly blamed himself. After all, when the company closed, around 100 people were thrown into unemployment. Without the company, the Dellinger family no longer received dividend checks. Without the company, the community founded by Walter and Callie Dellinger dissolved. A new world was in the process of taking hold; with race relations being a key dividing line between the new world of equality and democracy and the old world of Dellinger Inc.

Buddy Mitchell was a part of that new world. As a city councilman he oversaw the establishment of Martin Luther King Jr. Day as a paid holiday for city employees. He stood at the crossroads between the progressive business culture of the 1970s and 1980s and a company that was stuck in the segregation era with no intention of changing. For the man who had spent the majority of his adult life giving his all to prop up the ailing company, its collapse was too much to bear. The plant’s closure in the mid 1990s broke Buddy Mitchell’s heart. Amongst the abandoned machinery, between the walls of the old Dellinger plant that he loved so dear, Buddy Mitchell took his own life in 1997; ultimately a victim of the company, culture, and family that he had striven to save. With Buddy’s death, the plant, which had been still for years, fell silent. No longer could one hear the break whistles, the creak of the floorboards, or the whir of the machinery. Those who spent their lives in the plant, who could tell which room they were in by the smell and temperature of the room alone, never returned. A world vanished.

Although Buddy Mitchell gave his life to preserve Dellinger Inc, it faded and disappeared. Buddy’s struggle inspired others though, namely his son David. To this day, David follows in his father’s footsteps, working for the Atlanta Preservation Center. Even though Buddy failed to save Dellinger Inc by bringing it into the new world, his son continues to preserve Atlanta’s history and pull it forward into a new age focused on democracy, equality, and progress. Buddy instilled the value of history in his son, and through him, continues to preserve southern history to this day.