Author: Jamie Bynum

Waterpower was crucial to the development of the textile industry in the southern United States, especially to communities at or above the fall line. Georgia Public Broadcasting defines the fall line as “a geologic boundary marking the prehistoric shoreline of the Atlantic Ocean as well as the division between the Piedmont and Coastal Plain regions of the state.” Aptly named, the fall line is known for its creation of waterfalls due to dropping elevation. This boundary was used to the extreme by textile mills, as early on all of their machinery was operated using exclusively waterpower. The southern United States had this advantage over the North since waterpower was not as efficient there. However, a major problem came along with the utilization of the waterfall for power: it was impossible for boats to travel directly from one point to another if there was a waterfall between the two points. Roads were not very reliable, especially in times of bad weather, which would cause some roads to become completely impassable. After the Civil War, waterpower and water transportation were relied on less and less as the implementation of railroads, steam engines, and electricity made its way into textile mills.

The main use of water for power came in the form of water wheels and turbines. Early textile mills relied on the types of water wheels that had been in use for centuries, but only had an efficiency of about 30-40%. Of course, with the early textile mills of the region opening at the peak of the Industrial Revolution, a more efficient manner of power production was sought out. By the end of the nineteenth century, water wheels had been upgraded to an efficiency rate of 80-90%. Alongside the development of more efficient water wheels was the implementation of water turbines. The main difference between traditional water wheels and water turbines was that water turbines were smaller and were placed horizontally, completely submerged in water. Soon, water wheels were replaced by water turbines that took up less space and were able to spin much faster. Some southern mill owners found these turbines to be so efficient that they continued to use them into the 1930s. The use of water turbines not only generated waterpower but electricity; by the 1880s, some mills used electricity from water turbines to operate all or part of their mill, light their mill, or light nearby cities.

Before the introduction of steamboats and levies to this region, transportation via water was more difficult than in other parts of the southeastern United States. Due to the location of these communities relative to the fall line, all types of boats had a hard time navigating the waterways of west Georgia. Small boats known as flatboats and keelboats dominated waterways above the fall line before the advent of the steamboat. Flatboats were generally eight- to ten -feet wide and between thirty- to forty-feet long and transported both freight and passengers downstream. The keelboat, on the other hand, was designed to go upstream using manpower via poles, rowing, or dragging. Water transportation upstream without any assistance was costly and time-consuming, so the solution was to apply the power of steam to boats. After their introduction in the early 1800s, steamboats quickly replaced keelboats in most parts of the South; however, flatboats remained competitive in downstream transportation until the 1860s due to their cost and improvements made to the construction and operation of flatboats. The initial impact of steamboats on inland rivers was not significant due to their inability to travel north past the fall line but became irreplaceable once levies came along.

Troup Factory, one of the first textile mills in Georgia having opened in 1843, relied exclusively on waterpower. However, the rushing water used for waterwheels came not from natural waterfalls but a man-made log dam constructed in 1829 for the grist mill that eventually became this textile mill. With the construction of a cotton mill to accompany the original mill that operated wool carding machines, the owners of the mill had a second dam made of rocks constructed below the log dam. These dams used raceway flumes to guide the water down a narrow path where it would fall from the side of the dam, creating more turbulent waters to push the waterwheels. Water was not always beneficial to the mills; Troup Factory flooded several times over the years, which would have made the wagon road shown in the below map impassable.

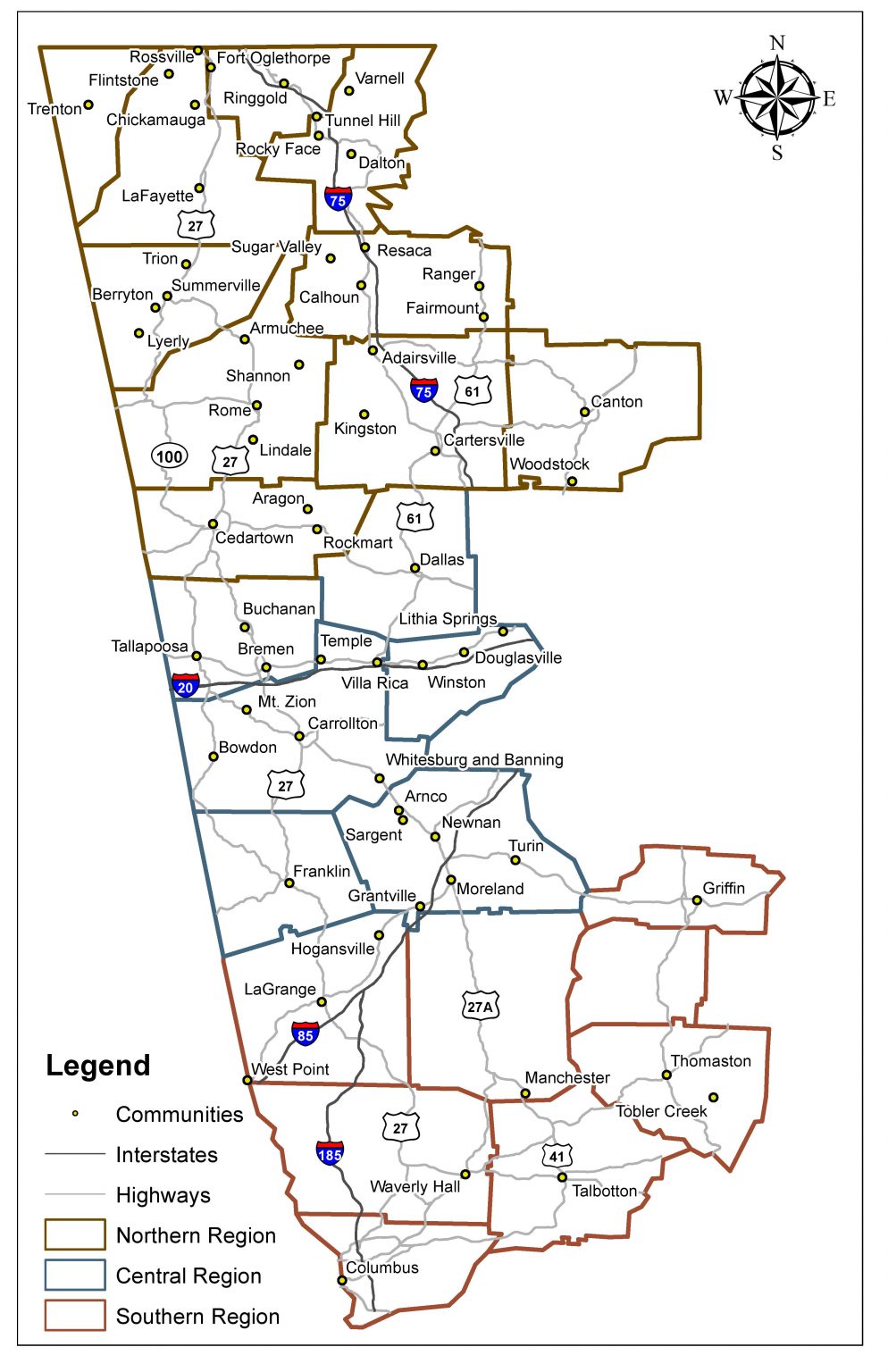

West Point, another early textile community in the West Georgia Textile Heritage Trail, also relied on waterpower and water as transportation. The Chattahoochee Manufacturing Company and the Alabama-Georgia Manufacturing Company, both located along the Chattahoochee River, began operations on the same day in 1866. In 1888, after the Chattahoochee Manufacturing Company had become the Langdale Mill of the West Point Manufacturing Company, the family that owned and operated the mill established the Chattahoochee Navigation Company. The goal of this company was to operate barges for the transportation of goods to and from the mill. The only alternative at this time was to attempt the five-and-a-half-mile wagon ride to the West Point depot. The fate of this company shows why water transportation was difficult in this region: when the water was too low, the shoals would be exposed and stop barges in their tracks, while high water levels would cause extreme rapids that were too difficult to navigate.

Columbus’ textile industry utilized water the most out of any community throughout the West Georgia Textile Heritage Trail. Several of the early textile mills in this town relied heavily on the powerful Chattahoochee River, just as the mills near West Point did. Two notable mills here were the Eagle and Phenix Mills and Bibb Manufacturing Company. Eagle Mills opened in the mid-1800s and was re-established after the Civil War. Once reestablished, it absorbed a nearby mill, making it one of the largest mills in the state; this achievement was accomplished using waterpower and transportation to produce goods and rapidly grow the company. The other prominent mill along the river, Columbus Mill owned by Bibb Manufacturing Company, was established in 1900 around a dam site that could be used to power the mill. As seen in the below image of Bibb Manufacturing, the surrounding area was not suitable for boats to pull right up to the mill.

Water was an incredibly important resource for early textile mills in the West Georgia Textile Heritage Trail, as it was used for both power and transportation. Early roads were often unsuitable for anything more than small freight loads going short distances. The use of water in many places allowed larger deliveries to be made to and from textile mills and was the best mode of transportation until the implementation of railroads throughout the state. Waterwheels were used to power the various mills throughout the region until steam engines and turbines were introduced. Steam, in the end, replaced water for both transportation and power.