Author: Jamie Bynum

On September 01, 1934, a massive strike that would last only three weeks would begin in the southern United States. Officially known as The General Textile Strike of 1934, and unofficially as The Uprising of ‘34, this strike led to textile mills shutting down for a brief period, arrests, fights, and unfortunate deaths. This strike would be the largest conflict of the National Recovery Administration (NRA) of the Great Depression.

Unrest within the textile industry came from several places. A major factor that played a hand in all of this was the Great Depression, which caused wages to fall. Mill managers and owners would stretch a few employees to cover the work of many while working only 30 hours a week. The reduction in weekly hours from 40 to 30 came from the passage of the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933 (NIRA). A Textile Industry Committee was set up to regulate the textile industry across the United States in favor of the workers, consumers, and business owners; however, it was quickly realized that only the interests of the business owners were taken into consideration.

Even before the Great Depression, the textile industry still faced “a period of declining prices, management cost-cutting, and frequent and largely unsuccessful strikes by workers.” The cotton textile industry faced especially significant issues with the decline of the cotton boom of World War I. When the war ended, the demand for cotton for wartime materials nosedived, leading agriculturalists out of their line of work. Textile mills moved now more than ever to the southeastern United States, where employees could be paid significantly less due to the large labor force of previous agricultural workers. Wages had already begun to take a turn for the worse, but the onset of the Great Depression caused even lower wages.

Due to these difficult working conditions, mill workers began getting more and more restless. One year before the strike occurred, mill workers began organizing unions, such as the United Textile Workers of America (UTWA). In September of 1933, the member count of this union was at 40,000; it quickly rose to 270,000. In August of 1934, a special convention was called from the UTWA membership; their demands were a $12 minimum wage for a 30-hour workweek. When mill owners didn’t take these demands seriously, mill operatives began striking and walking out of their jobs.

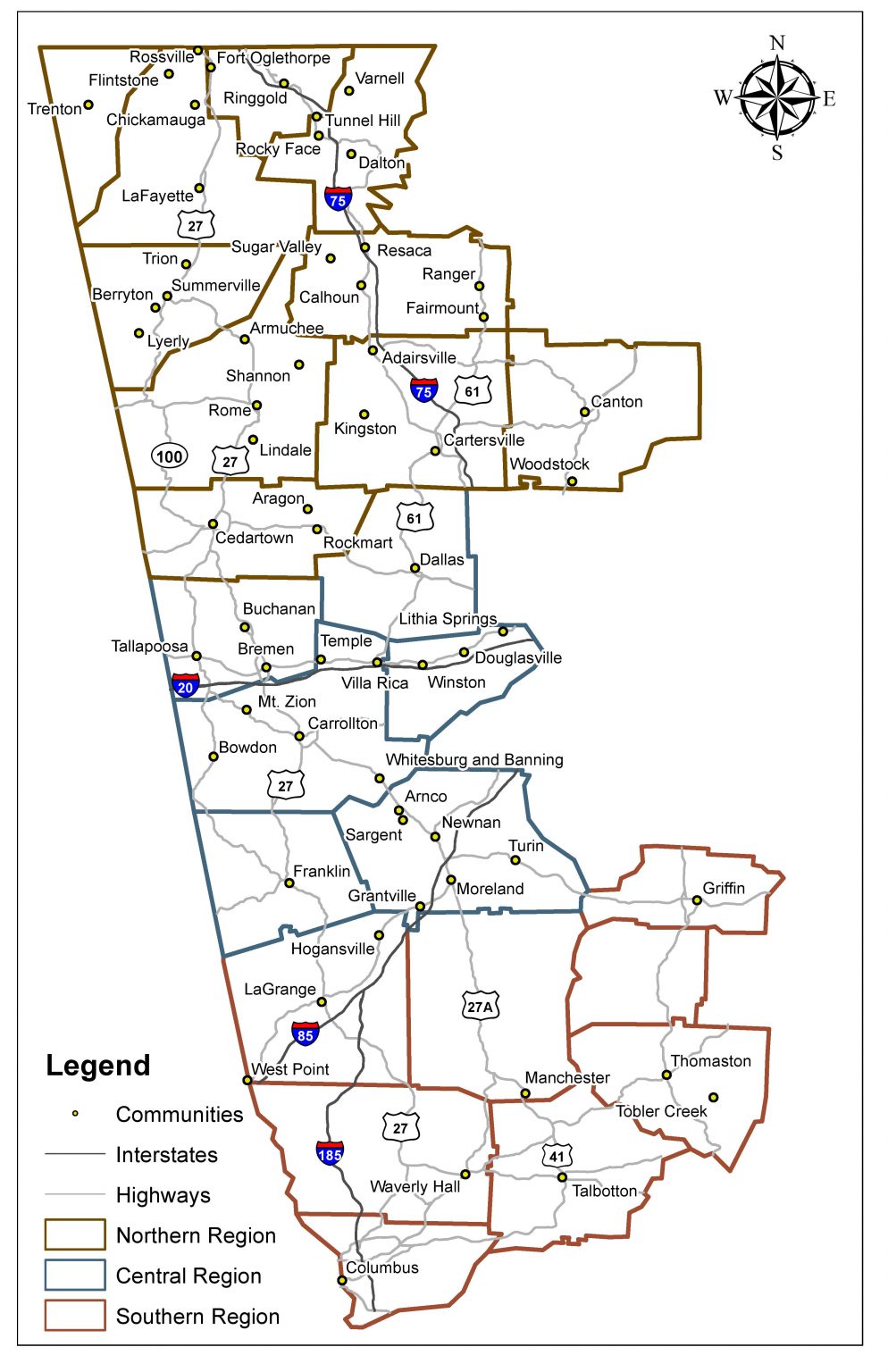

Cars organized as “flying squadrons” drove throughout southern Piedmont in an attempt to get other workers to go on strike with them. In Georgia, 44,480 of the state’s 60,000 textile workers had left their jobs by September 14. The National Guard was quickly called upon by governors to help quell strikes. Governor Eugene Talmadge declared martial law and had 4,000 National Guard members come to the state, who then began arresting thousands of people thought to be associated with the walkouts.

One of the first communities within the West Georgia Textile Heritage Trail region to see evidence of this strike was Trion. The vice president of Trion Mills, who also happened to be the mayor of the town, asked Governor Talmadge to send the National Guard, Talmadge refused. For the entire year before the strike began, employees held complaints of code violations, mostly relating to the extremely low pay they were receiving. Not only were the violations amended, but anyone associated with a union was harshly punished with eviction from the mill village. On September 05, the mill exploded in violence, so much so that local authorities had to swear in almost fifty special deputies to help protect the mill. Gunfire ensued, leaving two men dead and at least twenty men wounded.

Aragon Mills saw the death of a mill guard on September 15. A flying squadron of three cars drove past and shot at the mill, killing guard Matt Brown. A total of twelve suspects were rounded up and jailed. Before state troops could make it to Aragon, Rockmart’s deputy sheriff took it upon himself to deputize “loyal mill workers” and arm them with weapons to find where the squadron was believed to be camped. He claimed that he “intended to run every striker out of the county.”

In Newnan, no deaths occurred; however, 112 men and 16 women were taken into custody from East Newnan and transported to a detention facility at Fort McPherson. Flying squadrons set out on September 17 from Hogansville, Rockmart, and LaGrange to Newnan, where the mill workers were not for the strike. At Newnan Cotton Mills Number 1 plant, a group of picketers, sympathizers, and curious onlookers gathered around. Some of the picketers included heavily armed guardsmen and two planes circling overhead. A brief scuffle ensued, and the picketers were subdued. Those from Newnan were told to go home, while those from outside of Newnan were taken to Fort McPherson. Work quickly began in the mills of Newnan after the strikers were taken away.

In LaGrange, the uprising still took hold despite Callaway Mills ensuring every family had at least one full-time employee. Much of the trouble faced in LaGrange was hyped up by out-of-town flying squadrons. Strikers from this community began to travel with these squadrons to other communities to promote the strike. The National Guard detained picketers in this community. Unrest in this community did not stop with the General Textile Strike of 1934; they faced a second strike in 1935 in which martial law was again declared.

Columbus faced a completely different series of events. While there had been some violence in August, by the time the strike officially kicked off, there was none to be reported. This peacefulness was most likely due to the mills within the city closing their doors before things could get worse. Workers picketed outside of the mills, but they were generally good-natured. Dalton experienced no violence as well, even whilst keeping their mill in operation.

In Carrollton, no evidence of the strike was present until September 11, when a flying squadron rumored to have originated in LaGrange arrived at the Mandeville Cotton Mills. This squadron forced the mill to close down, and it remained closed most likely due to more squadrons passing through. Talmadge called in the National Guard to help arrest strikers at the mill several times. This call for help was when Mandeville was able to resume operations.

By the middle of the month, it was clear that no progress was being made to better the conditions of working within textile mills. The strike ended on September 23 when President Roosevelt intervened, asking the workers to return to the mills. The workers, however, were afraid to return to the mills and face retribution from the owners and managers. Many workers were fired from their jobs, forced out of the mill villages that housed mill workers, and “blacklisted” from working in any textile mills ever again. As for those held at Fort McPherson and county and city jails, they were quietly released, most of them never to face the charges of the strike.

Graduate student Allison McClure worked with ArcGIS Story Maps to create the map below outlining the impact of the General Textile Strike of 1934 throughout the rest of the United States.

“The Industrial Revolution in the United States of America bred multiple successful businesses and industries across the country. Investors and business owners saw great financial and commercial success from their factories and plants, but the people working hard manual labor suffered physically, mentally, and financially. The textile industry on the East coast boomed throughout the early twentieth century. The poor, working-class Americans who staffed these factories endured harsh working conditions for very little pay, but during the interwar period and the Great Depression, workers began to demand better treatment from their employers.

The General Textile Strike of 1934, also called the Uprising of ’34, occurred as a result of workers organizing against their employers to demand better wages and work environments. Through the influence of unions, like the Textile Workers’ Association, employees of large textile conglomerates went on strike and faced police brutality and elitist government officials in days-long strikes that resulted in workers being injured and even killed. In Georgia, factory workers in Trion, Augusta, and LaGrange participated in movements that shaped the textile industry in the state forever. While individual strikes in some states ended in death and sadness, the strike led many factories to implement wage increases, safety measures, and even allowed workers to organize in some cases. Overall, the General Textile Strike is important to study and present in a format like ArcGIS StoryMaps because it shows how a major labor movement moved from Northern states to Southern states, and it shows how different states treated strikers and met their demands.”

Leave a Reply