Author: Tennesse Mena

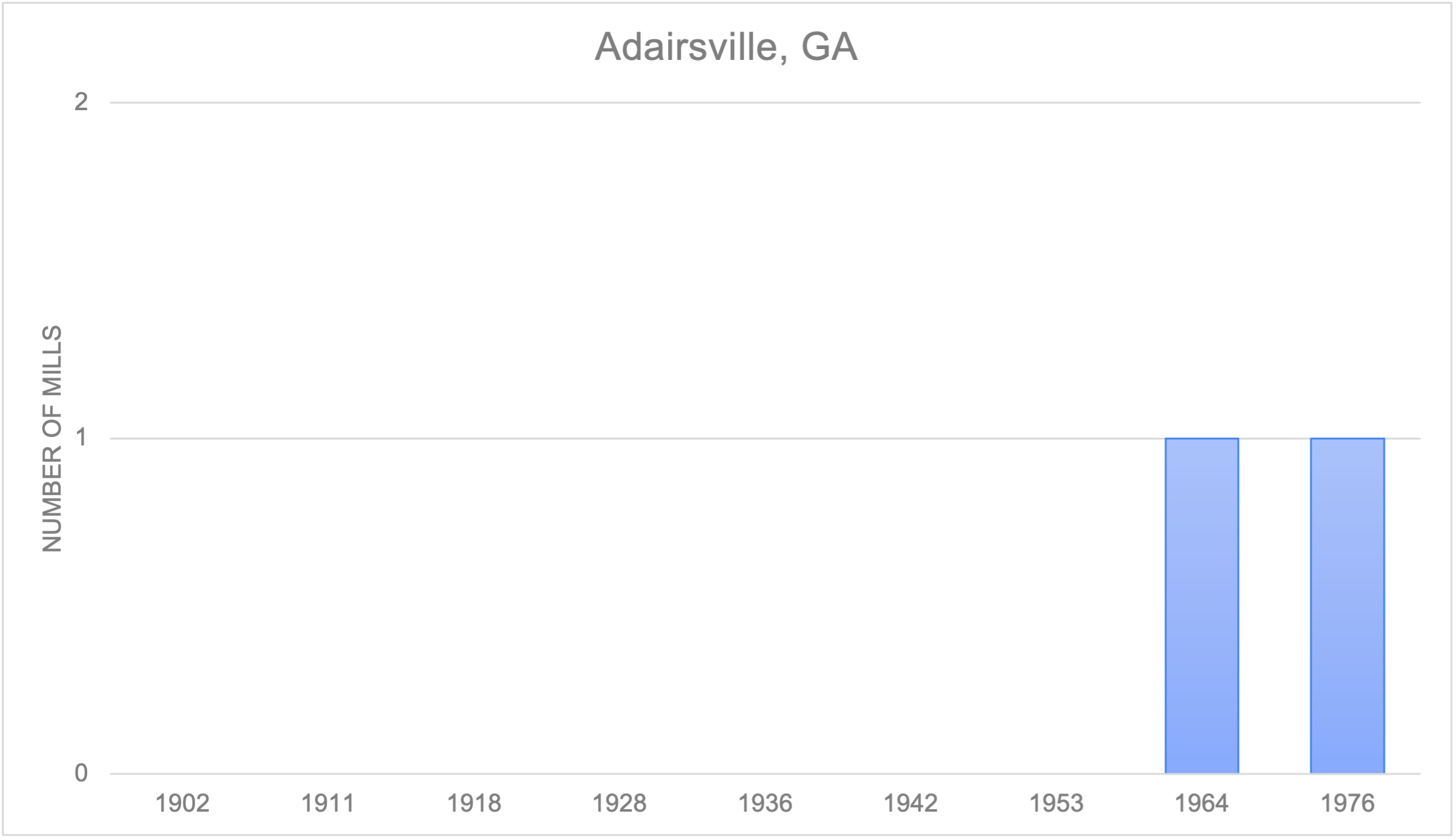

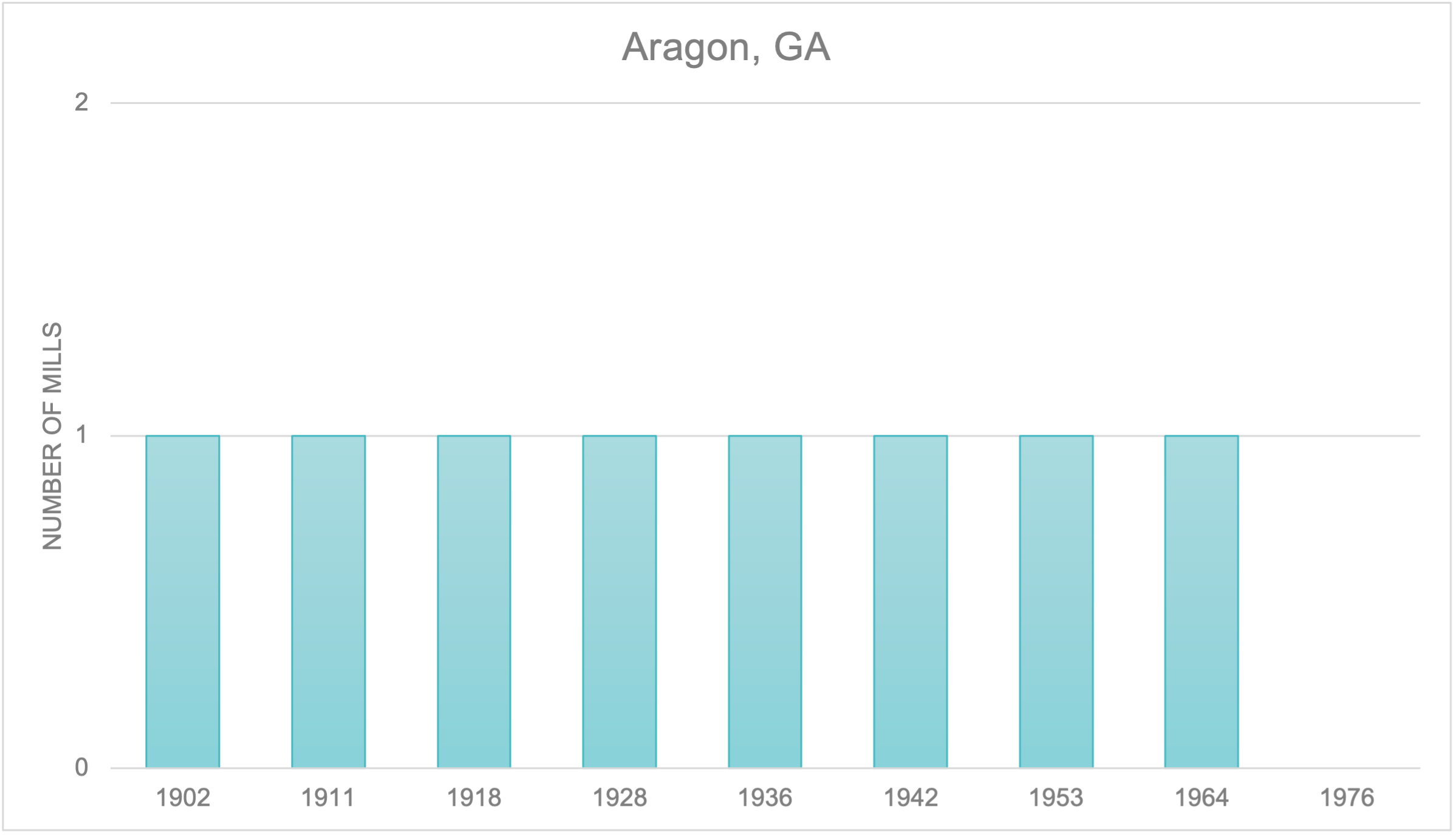

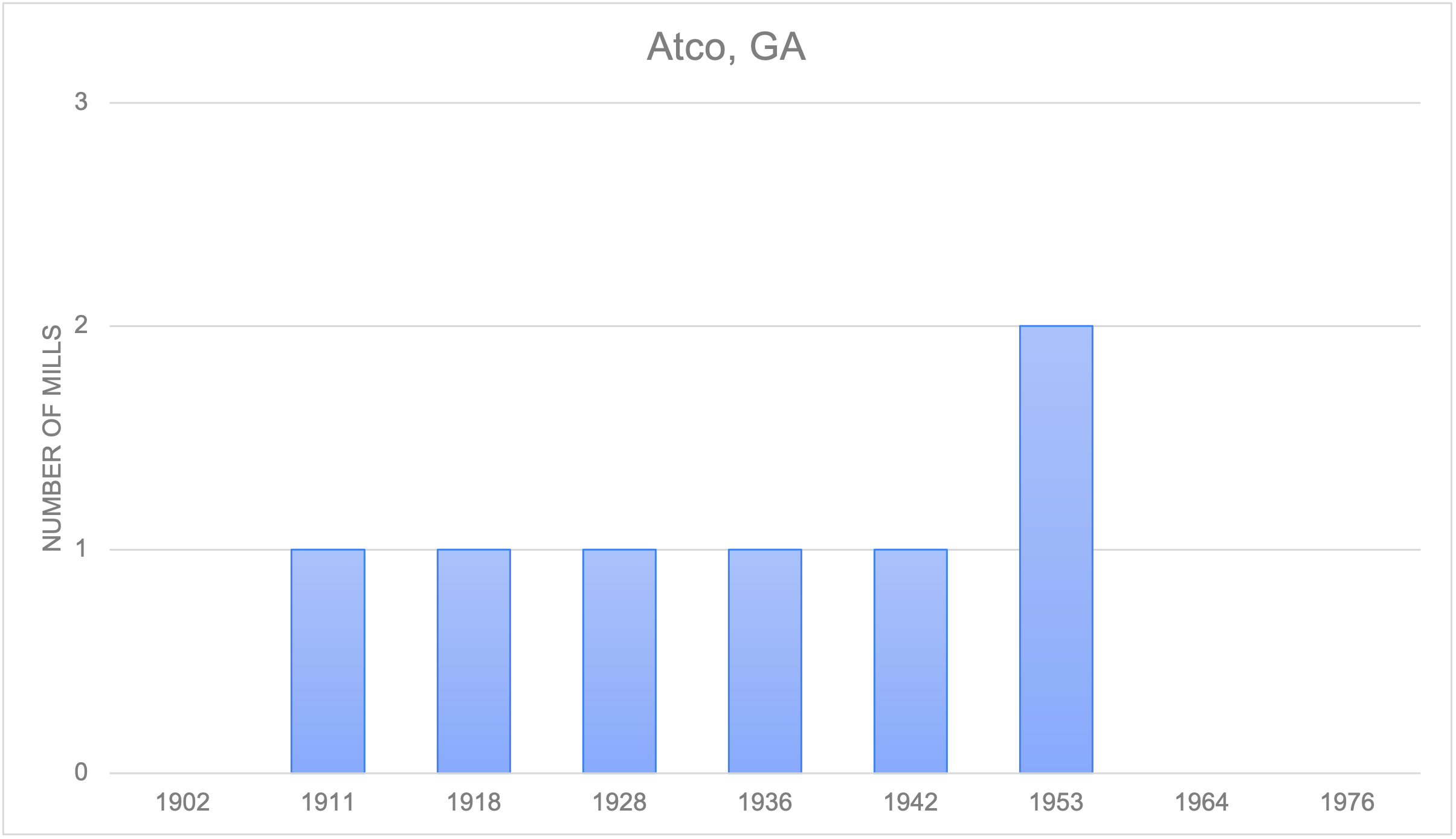

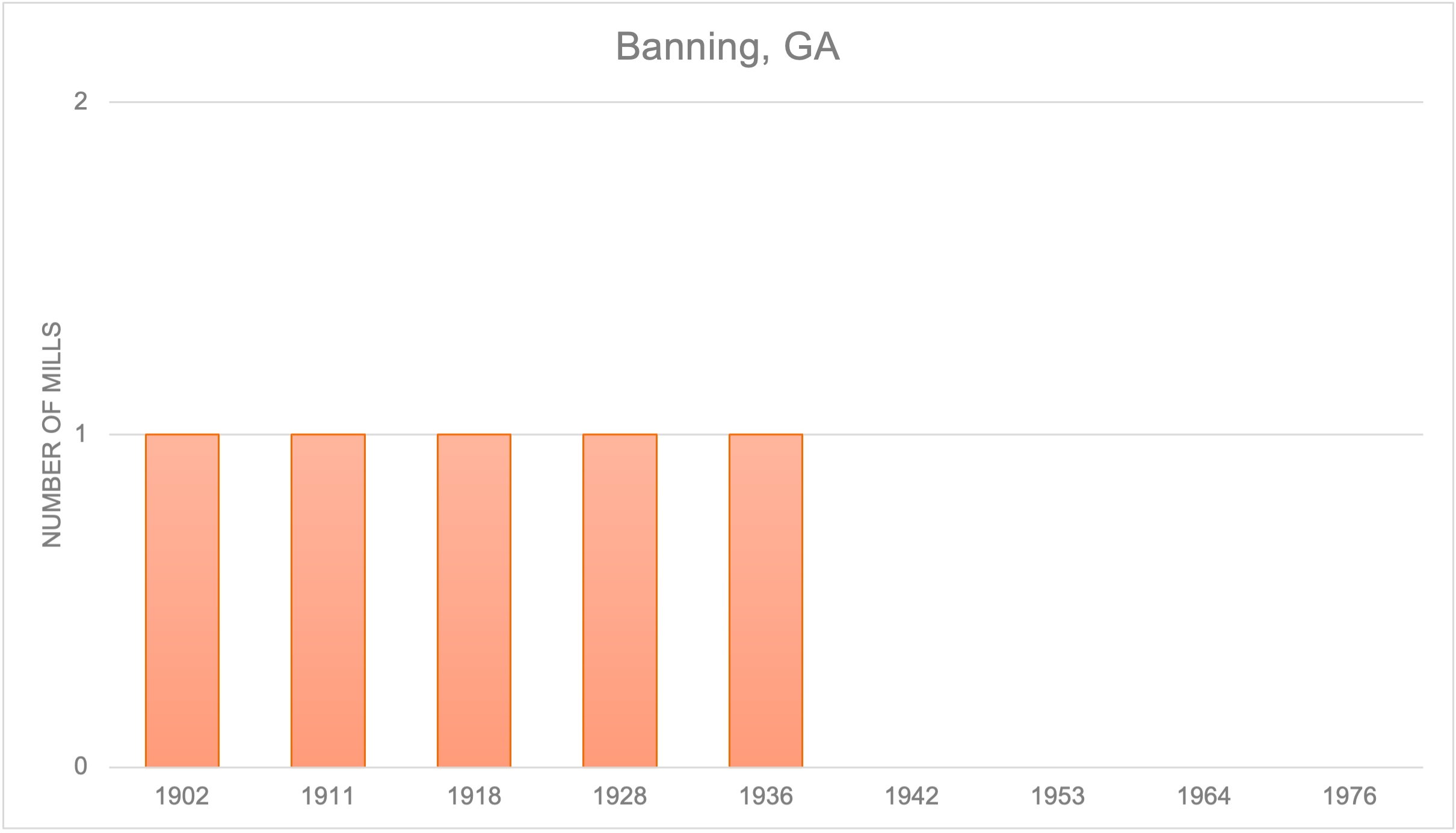

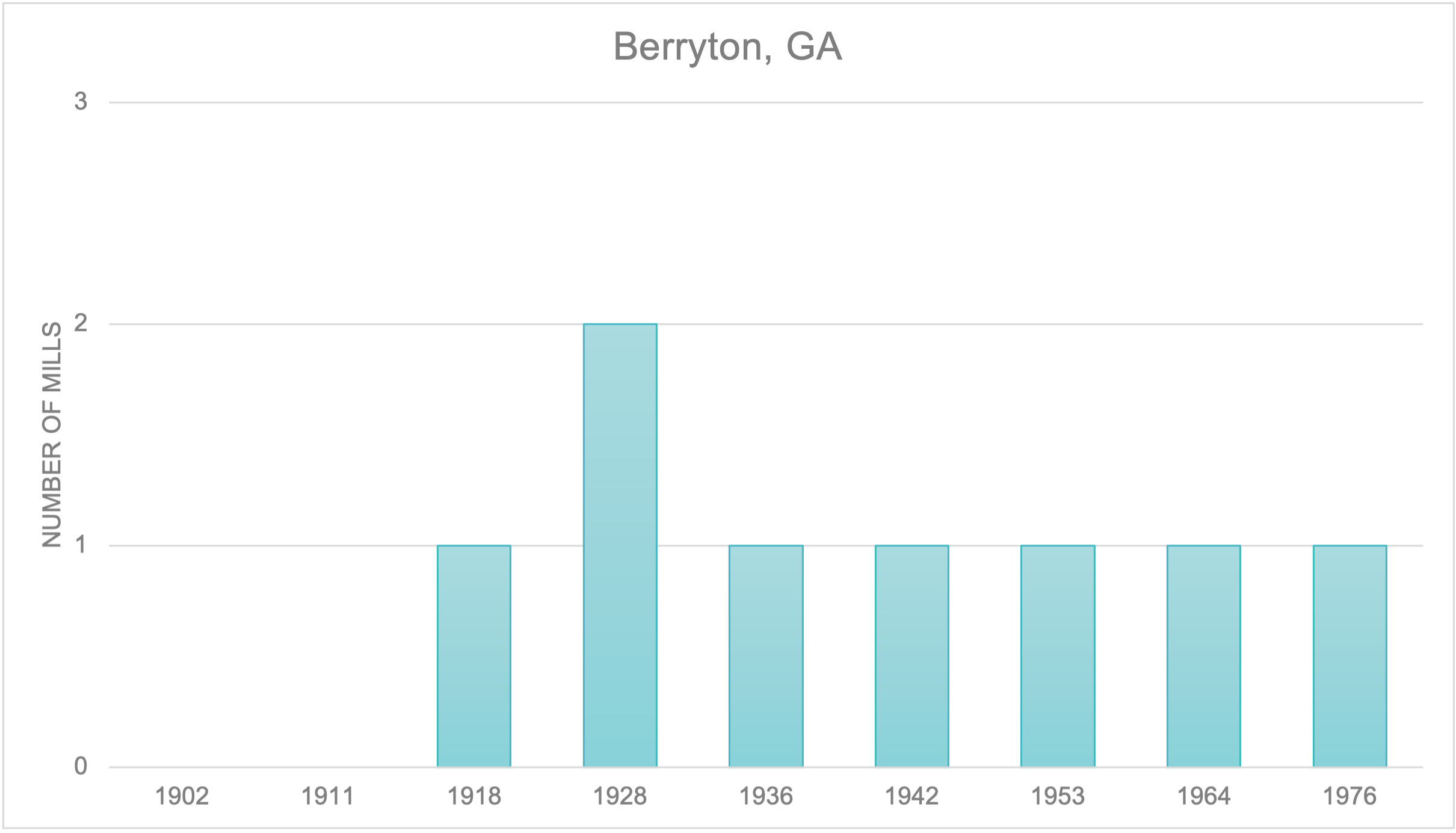

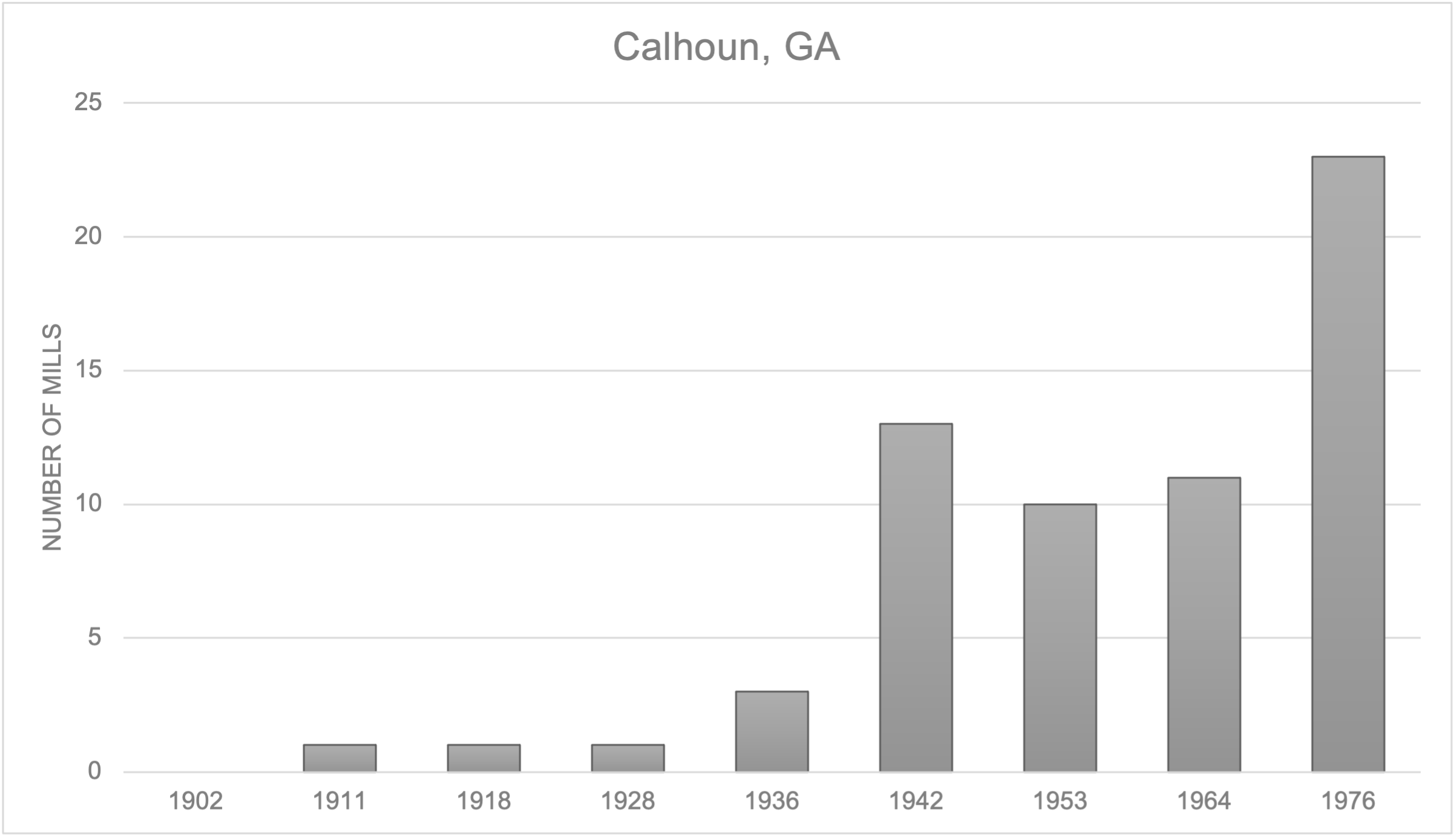

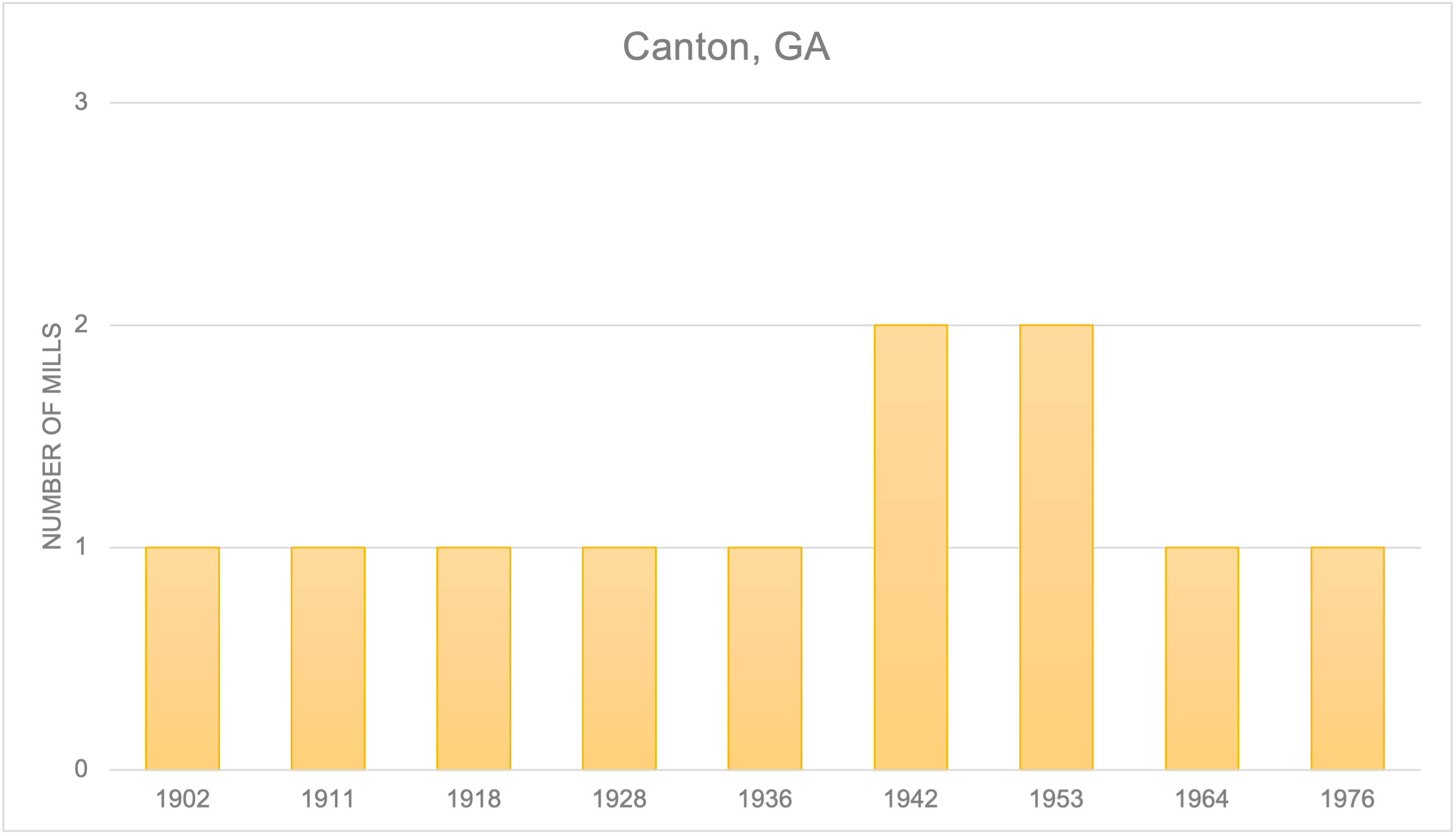

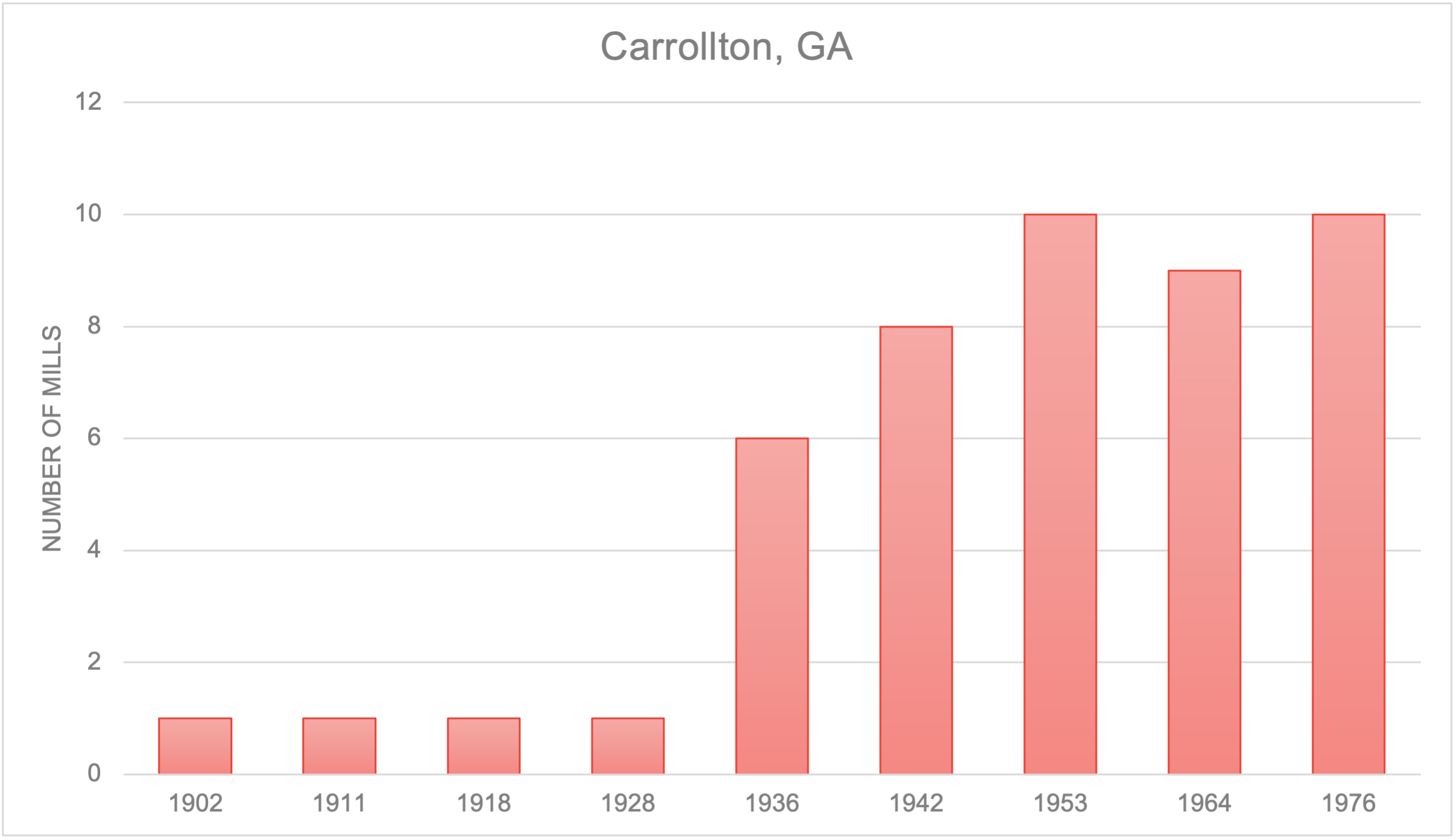

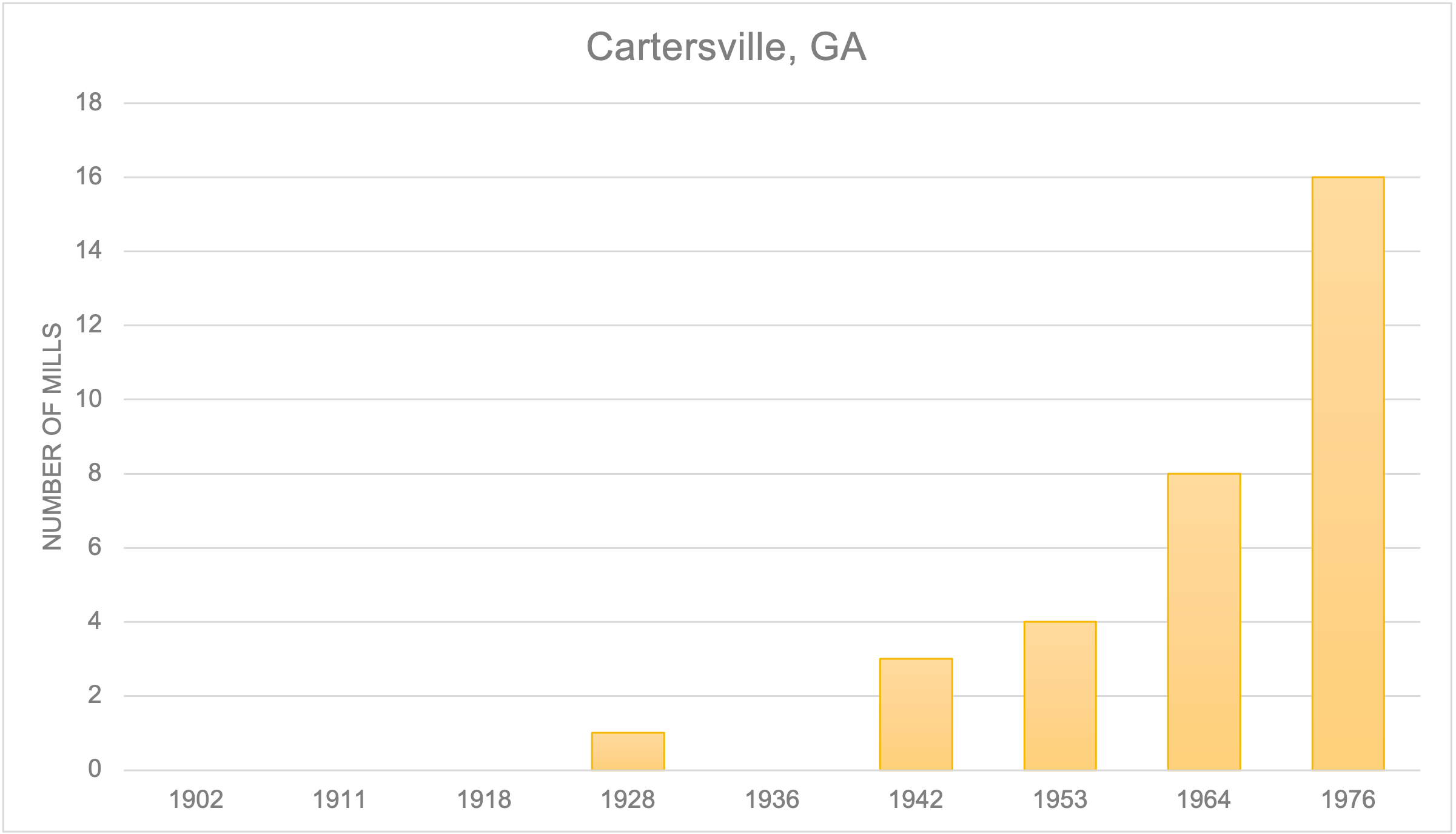

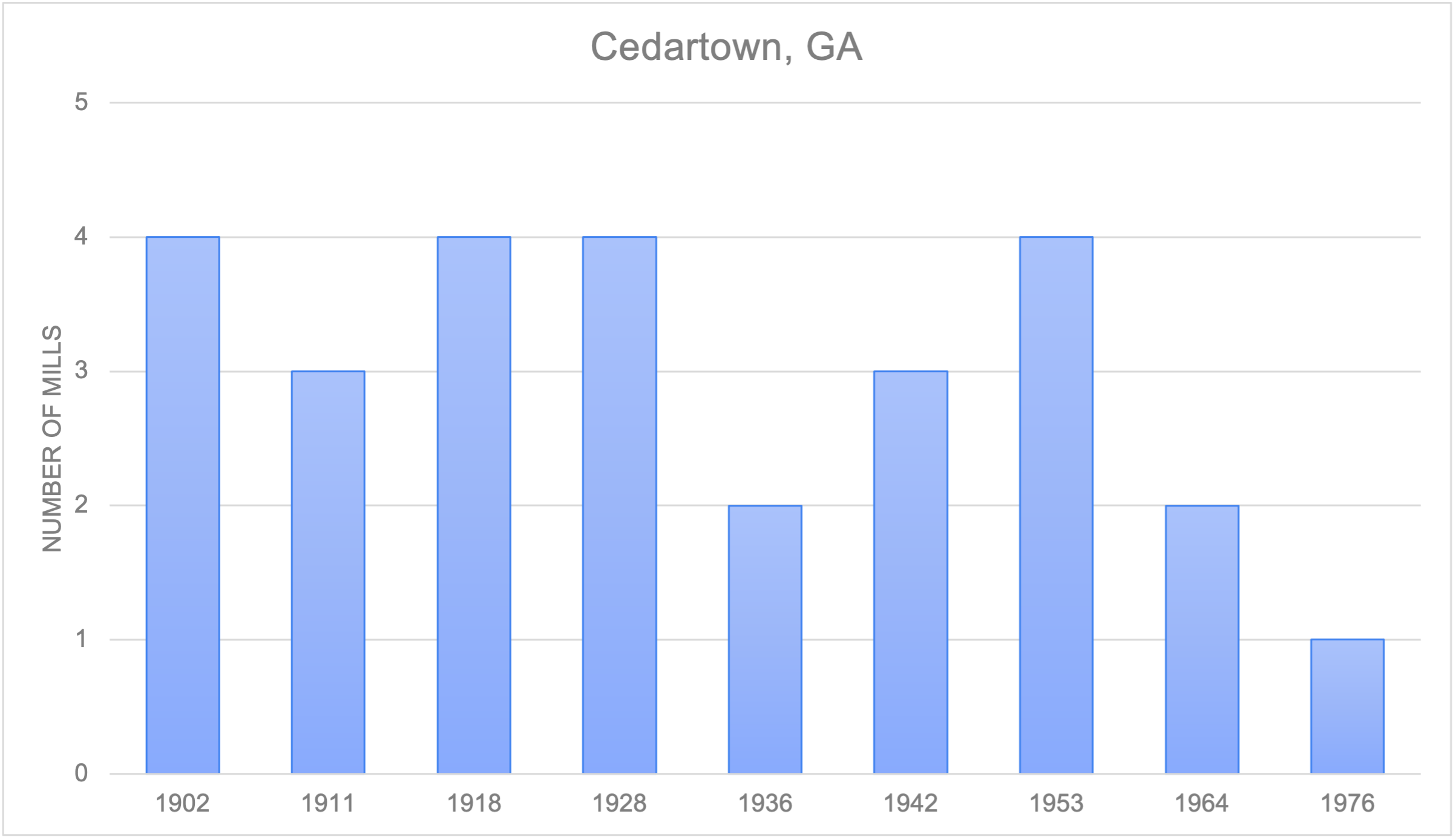

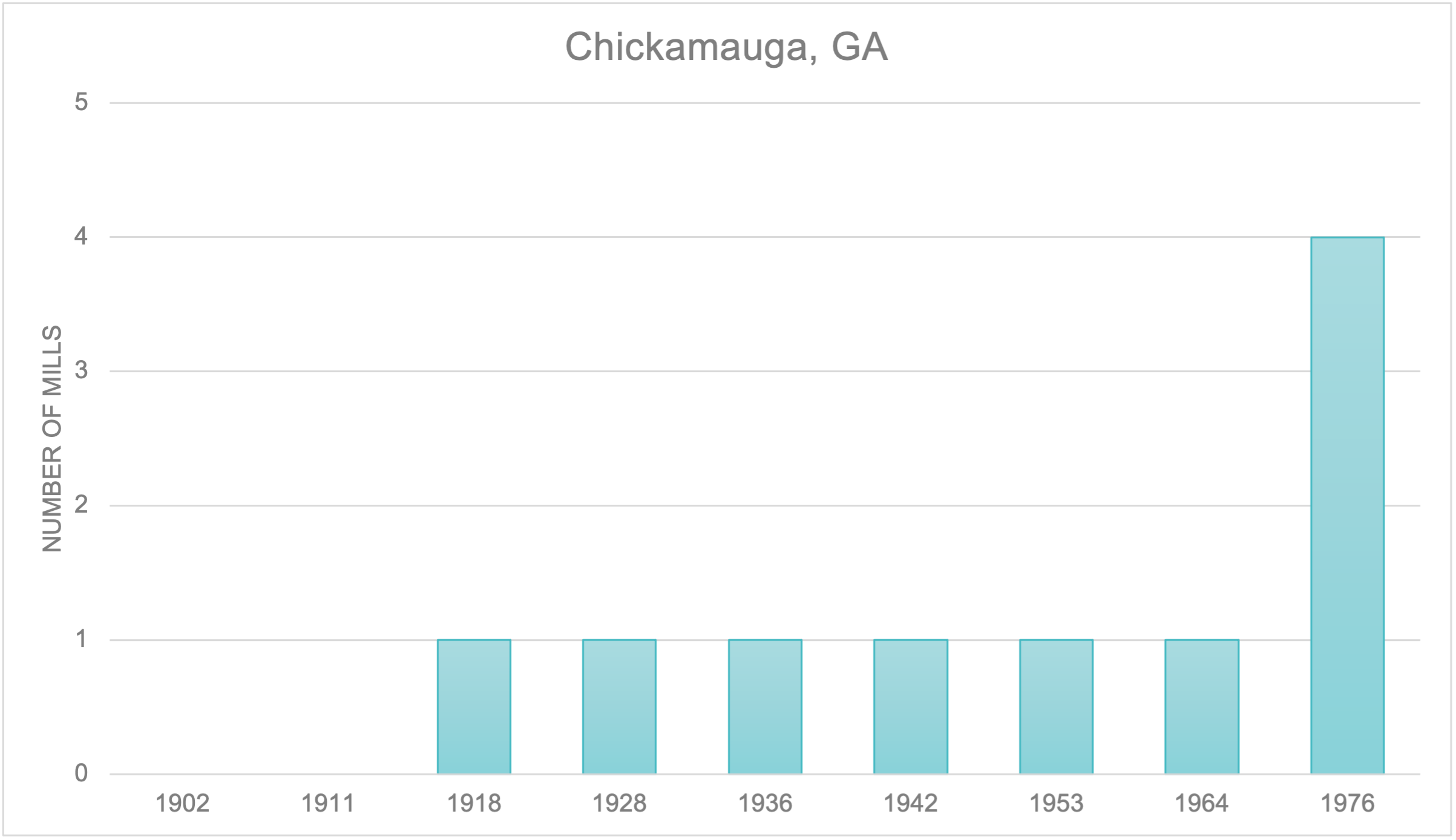

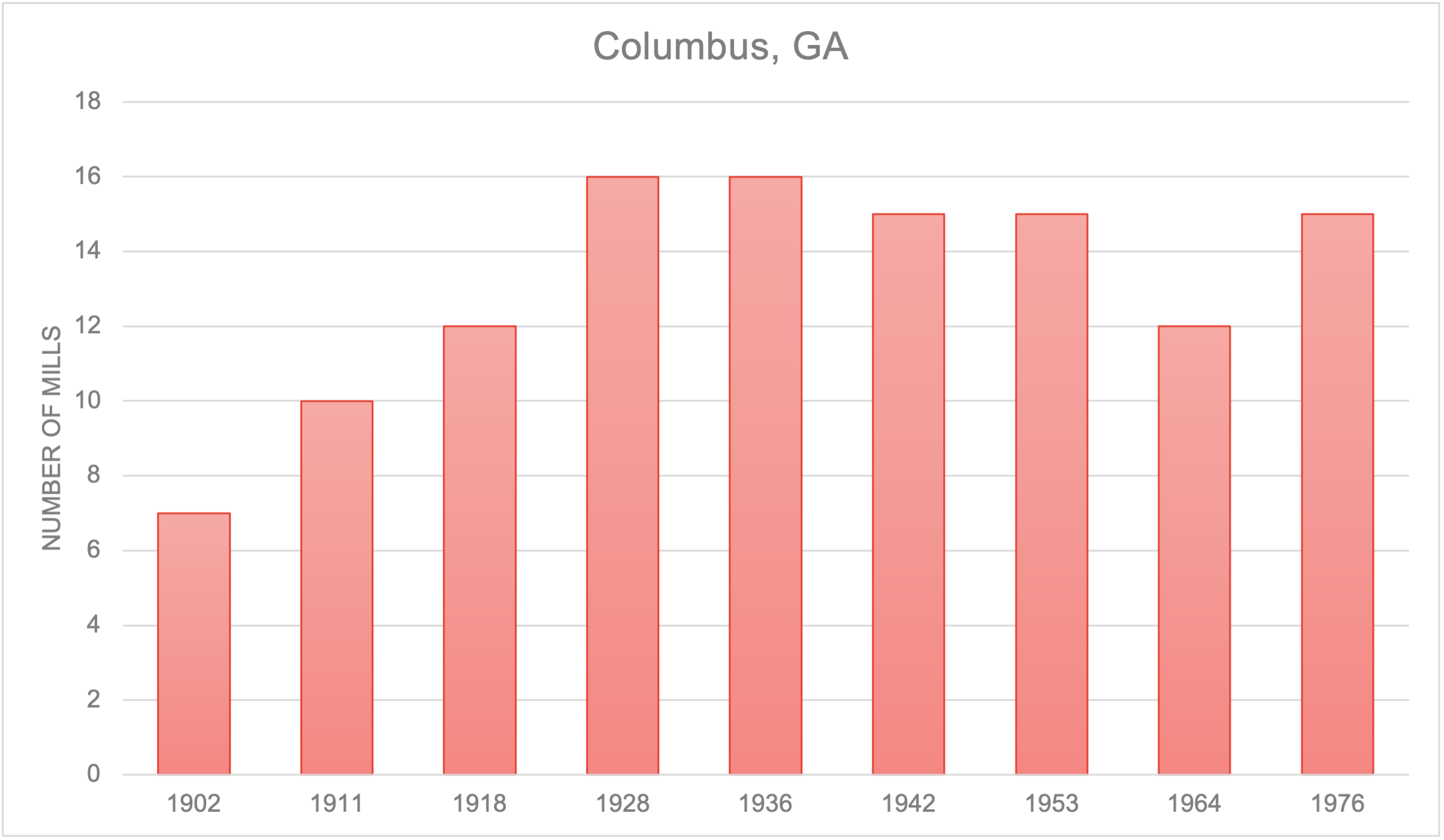

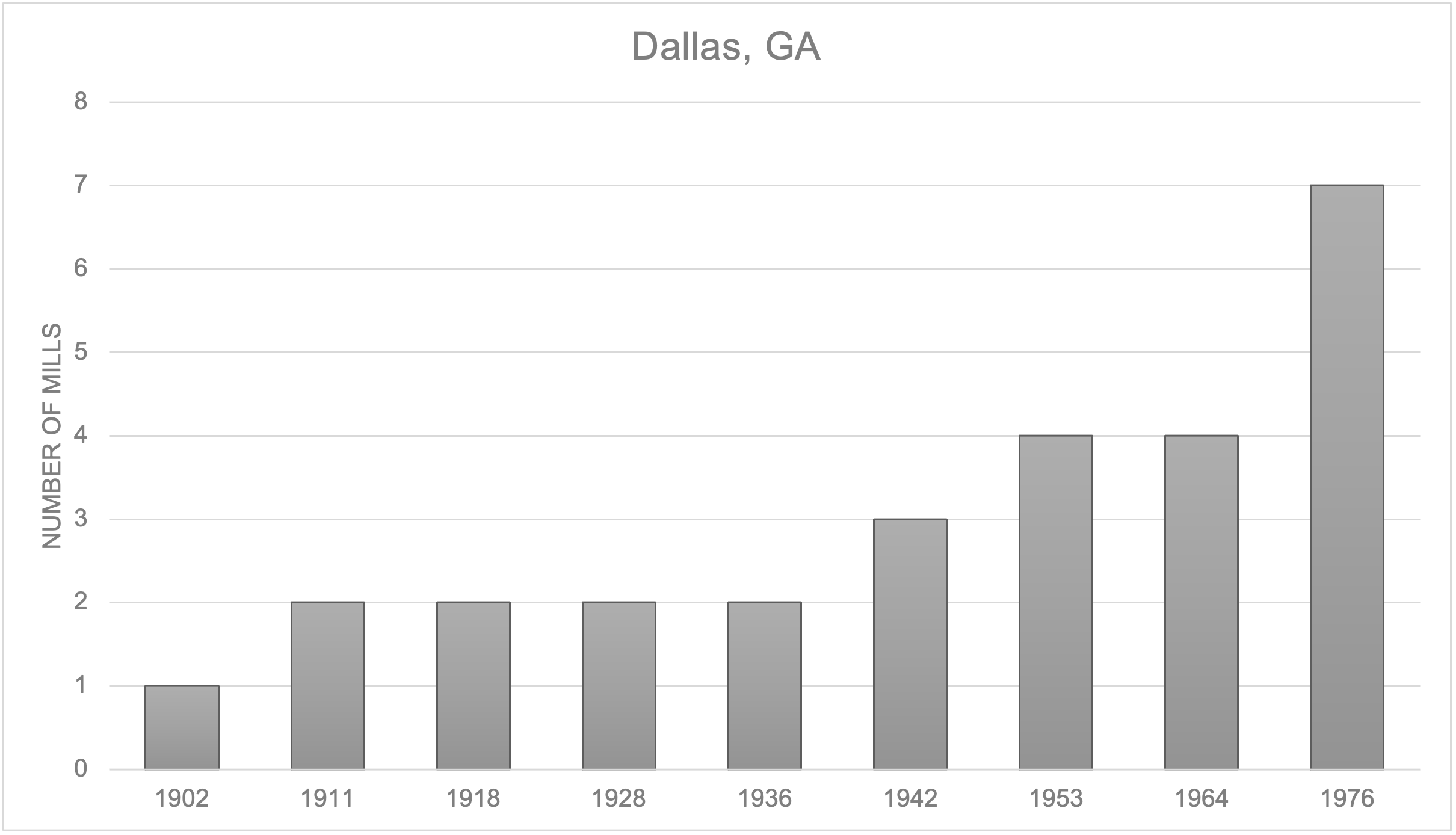

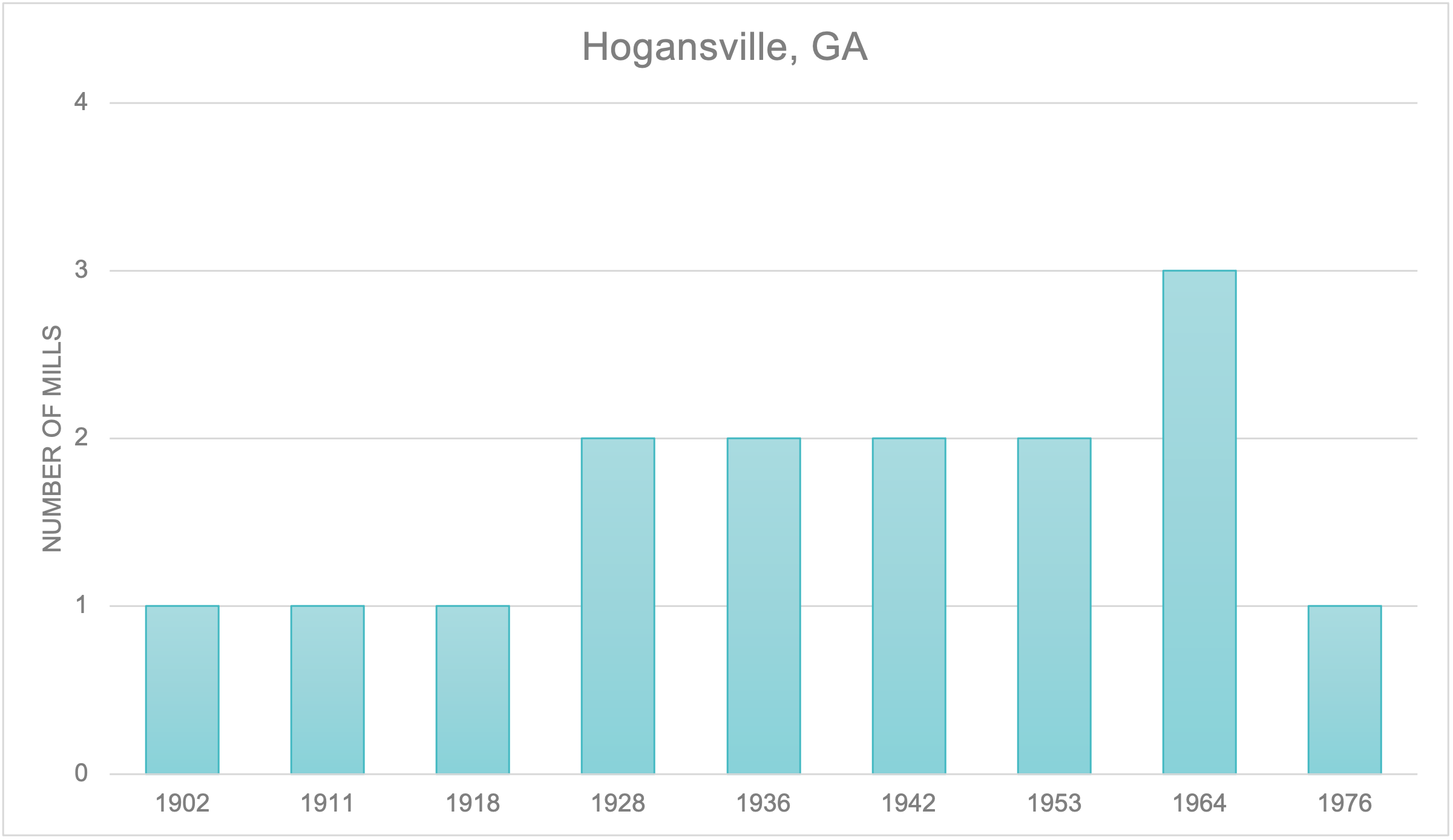

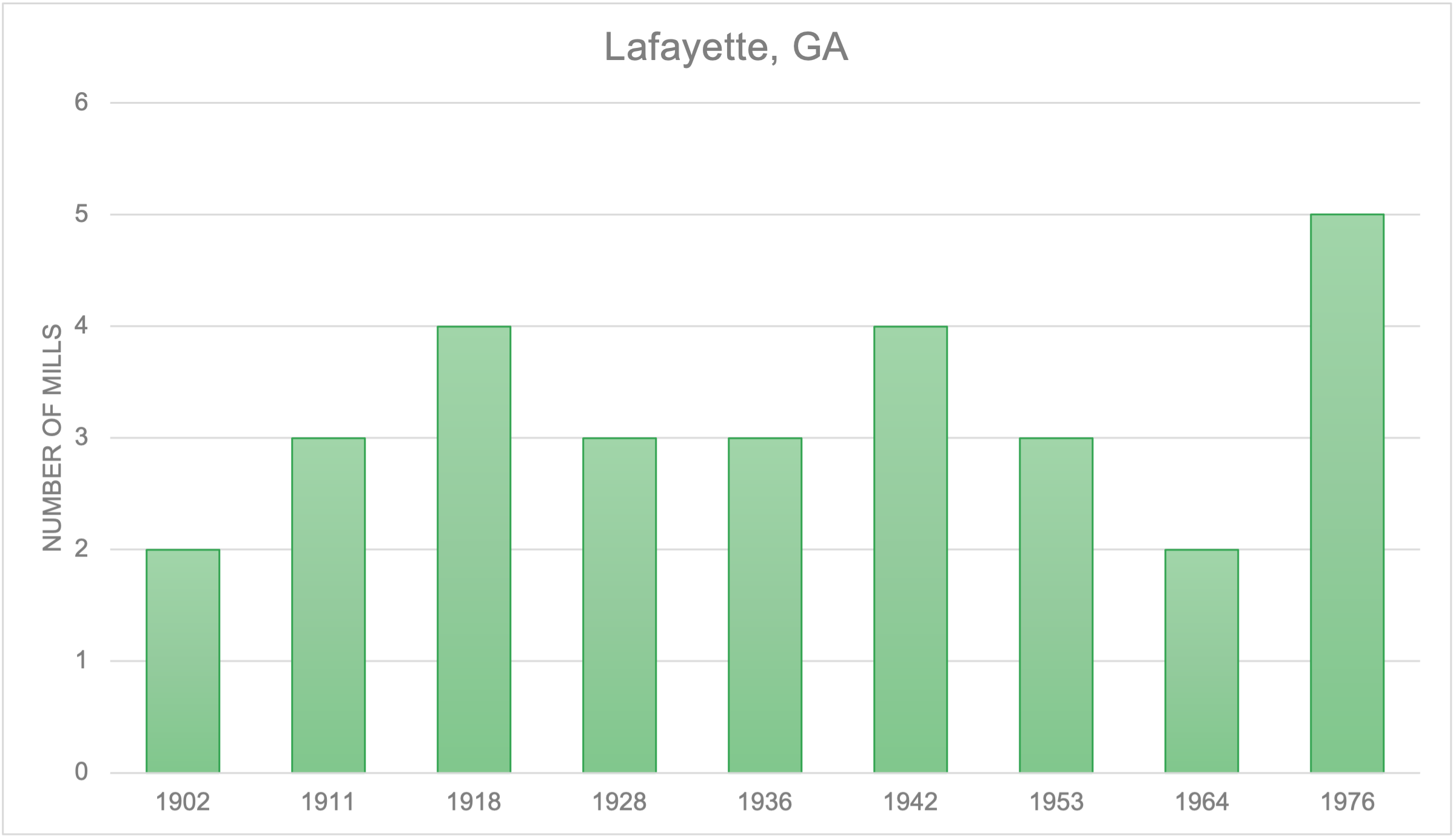

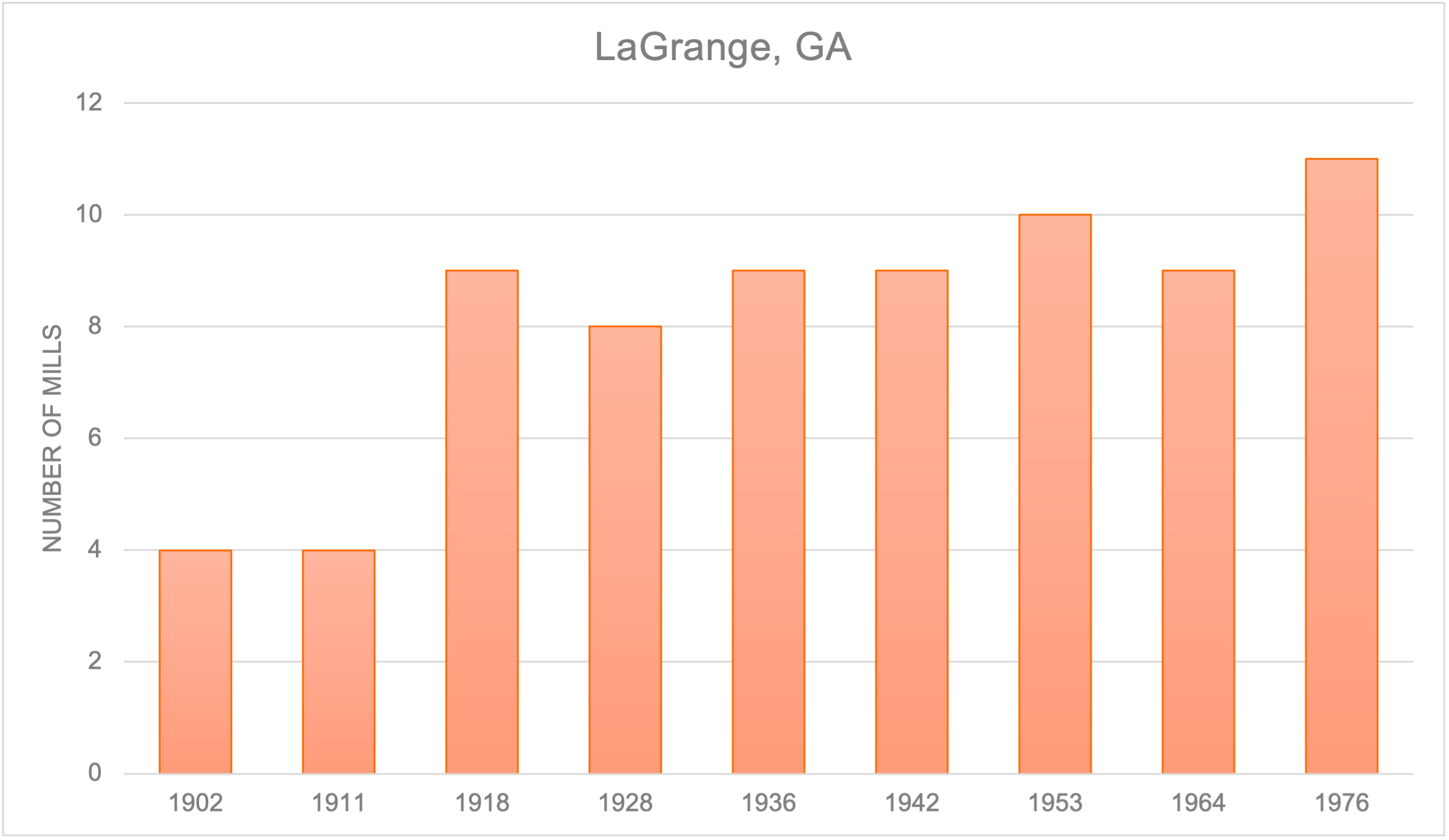

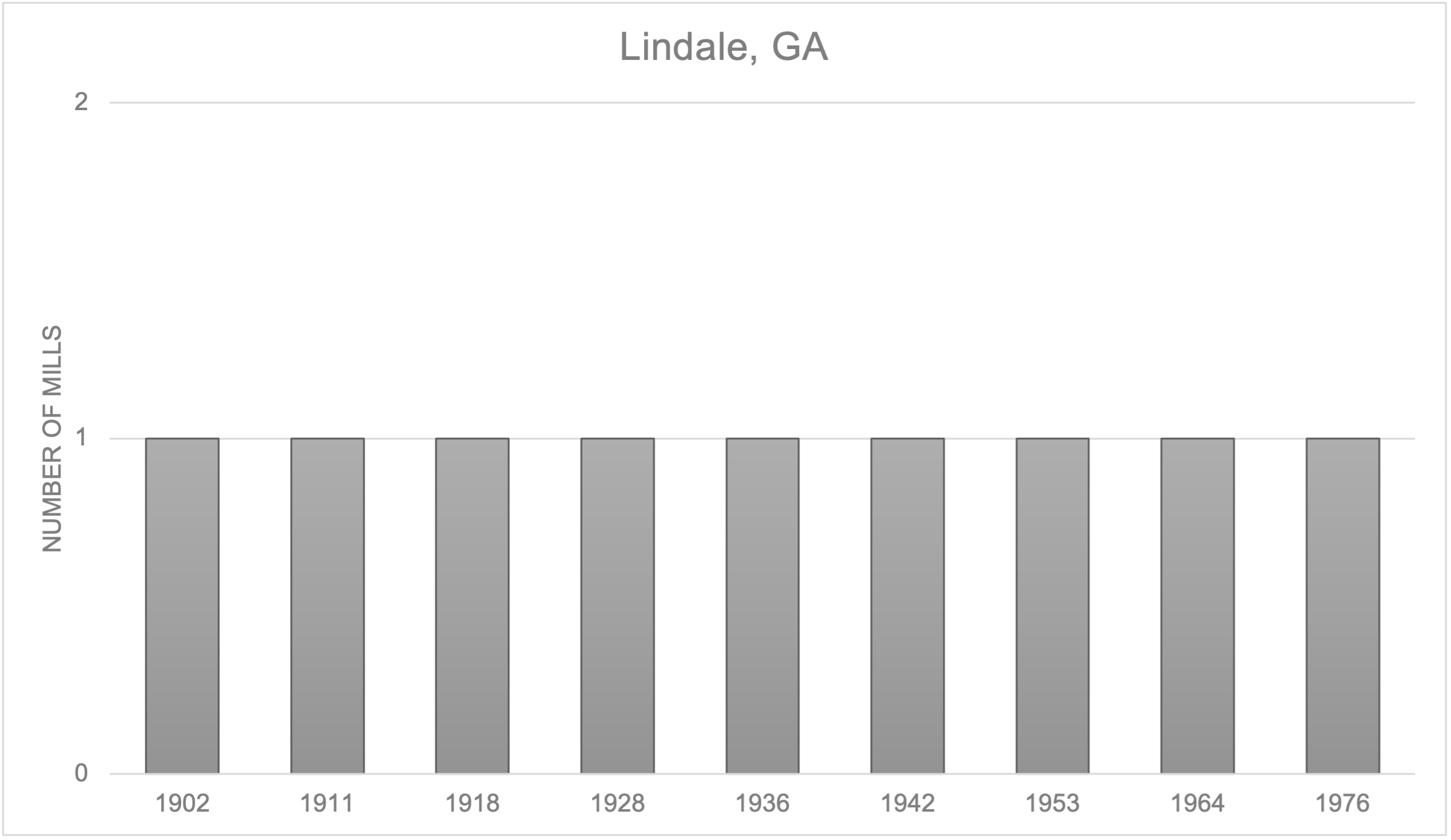

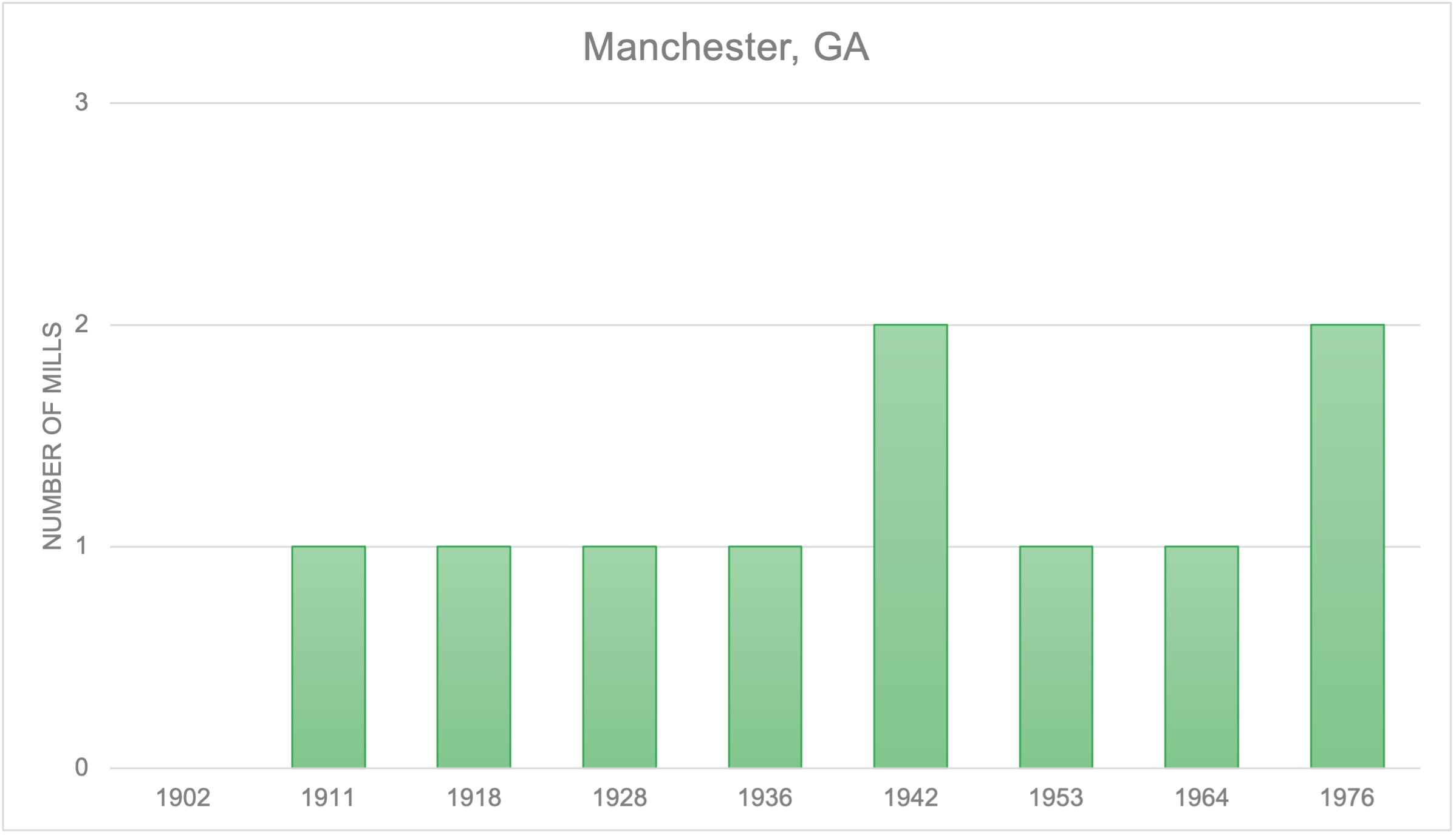

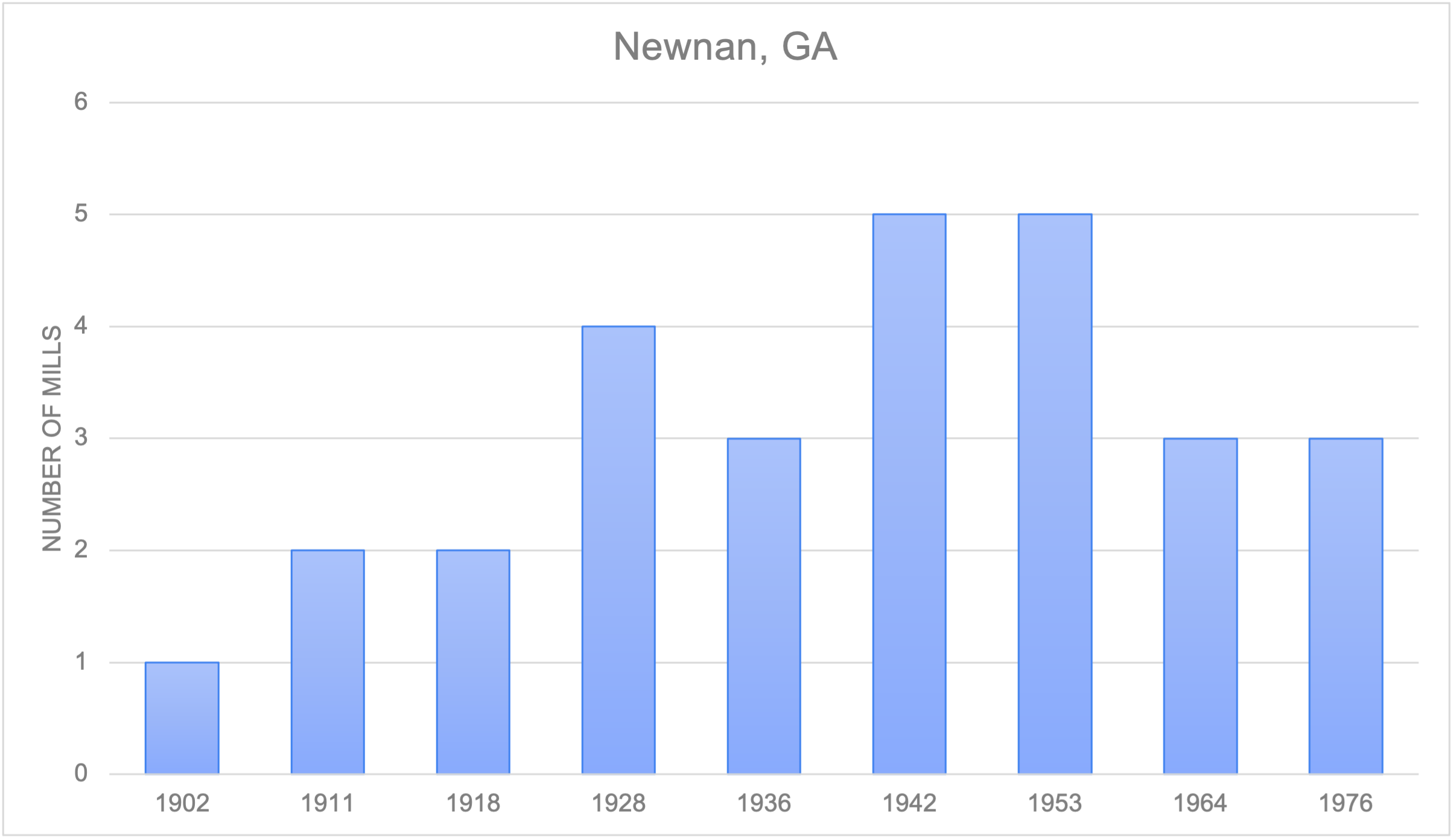

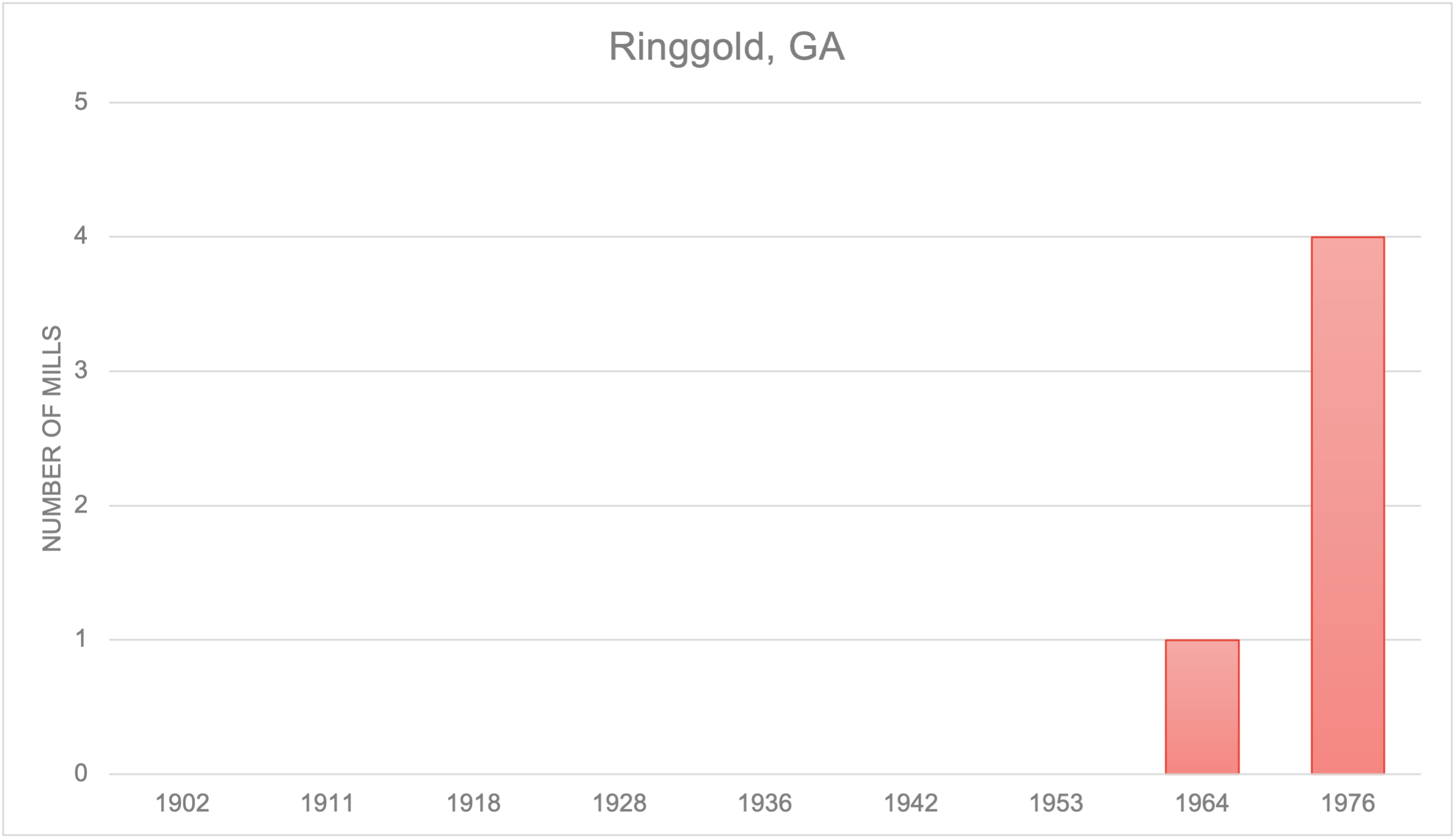

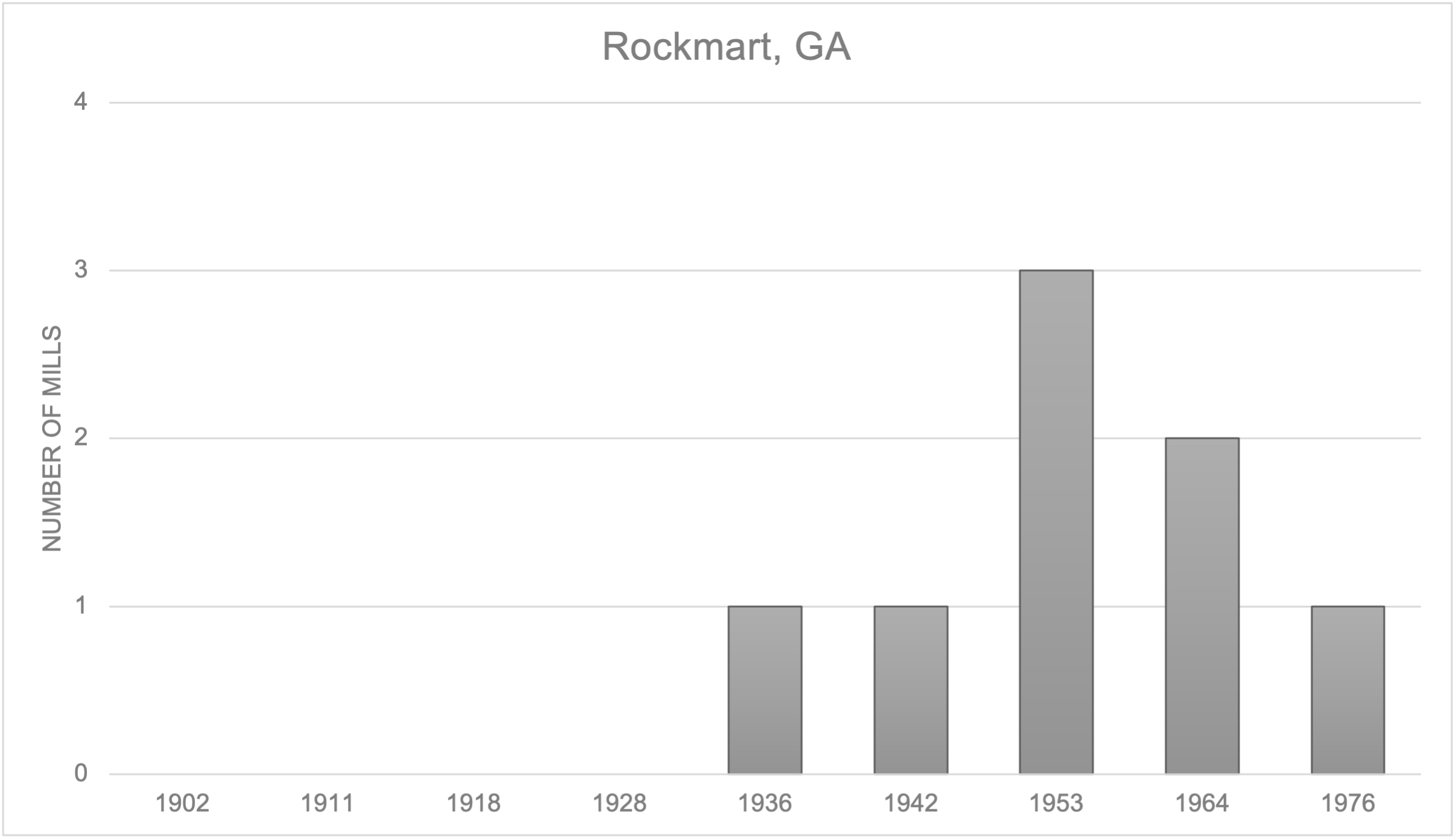

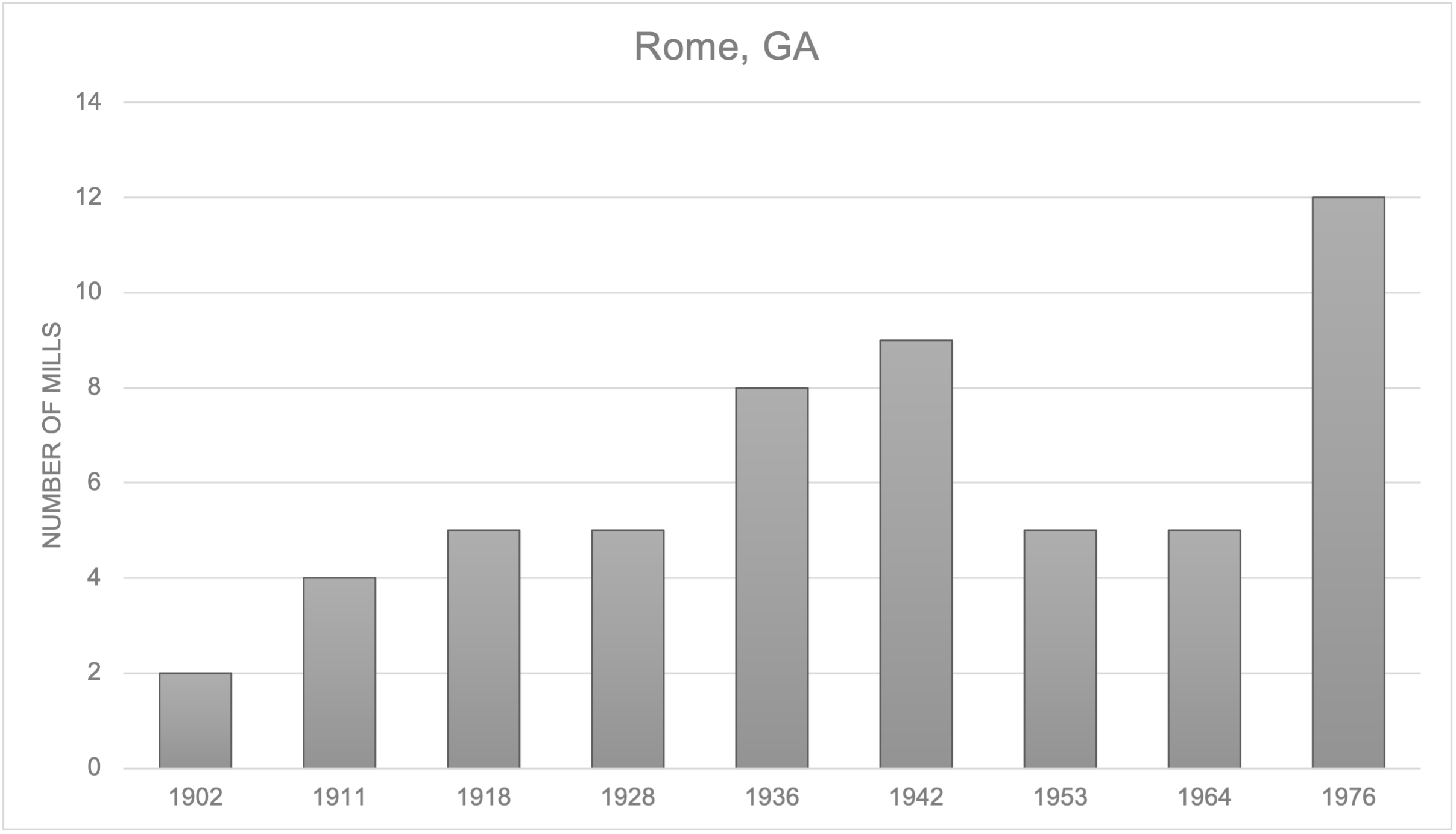

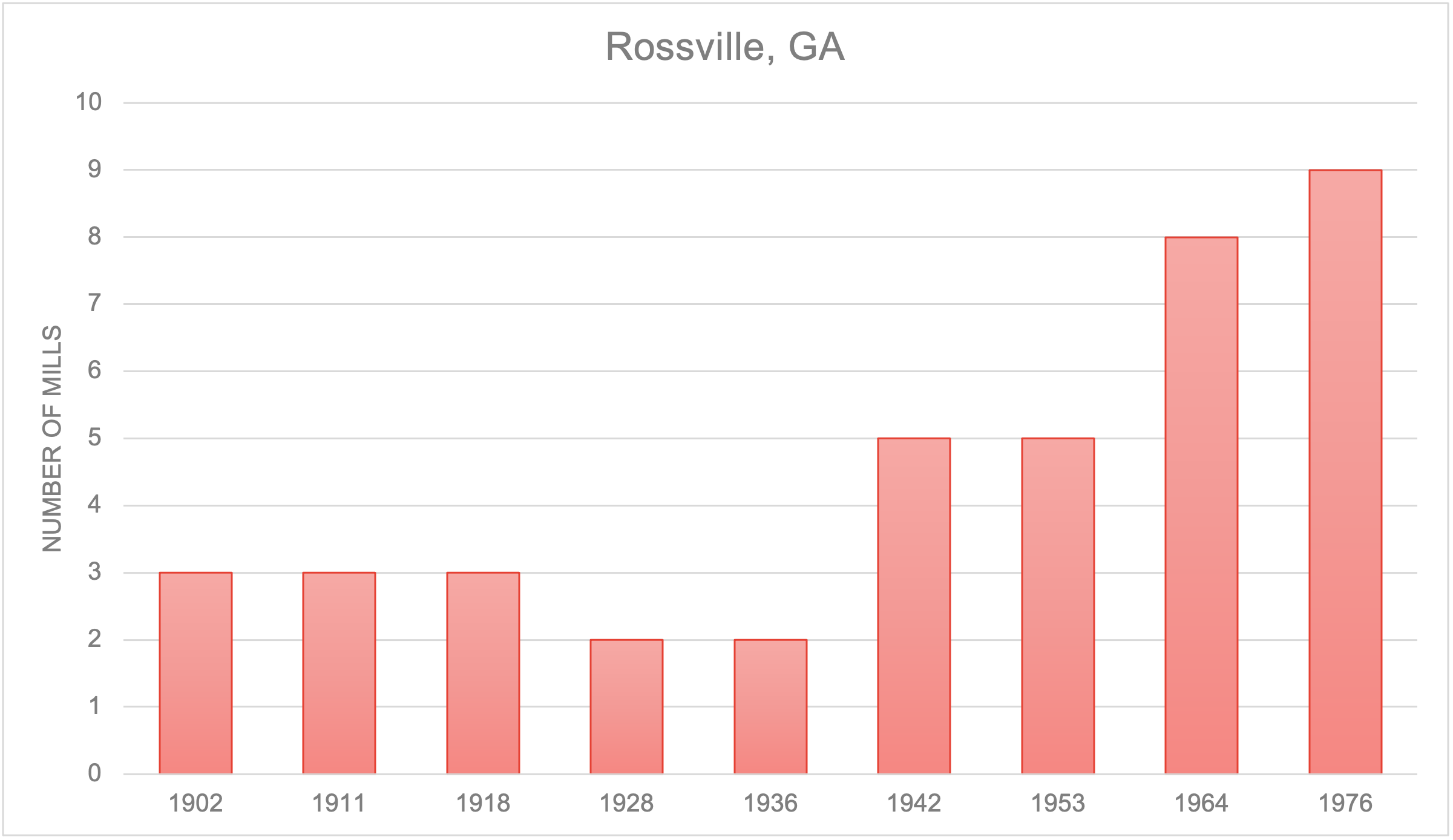

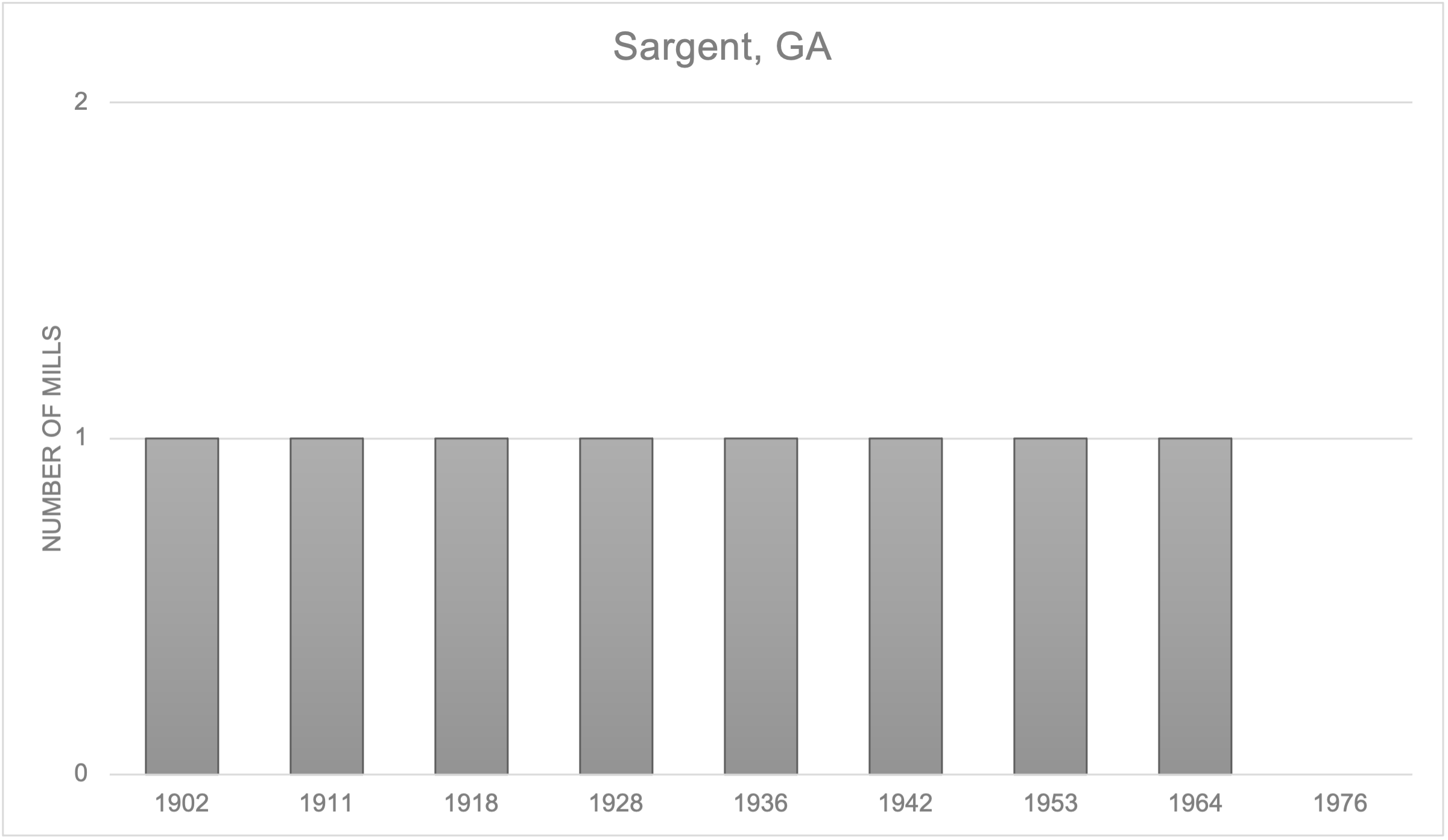

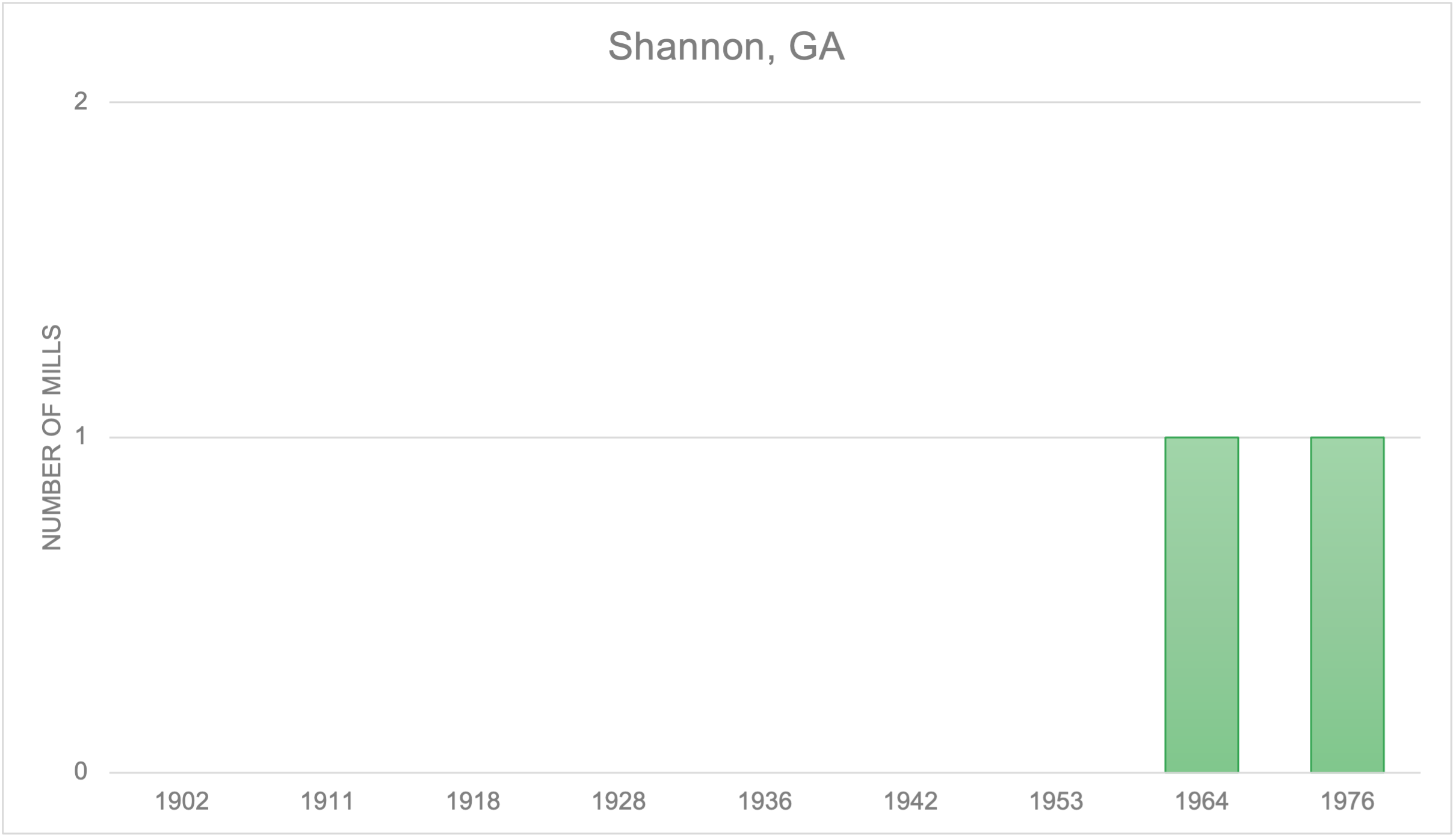

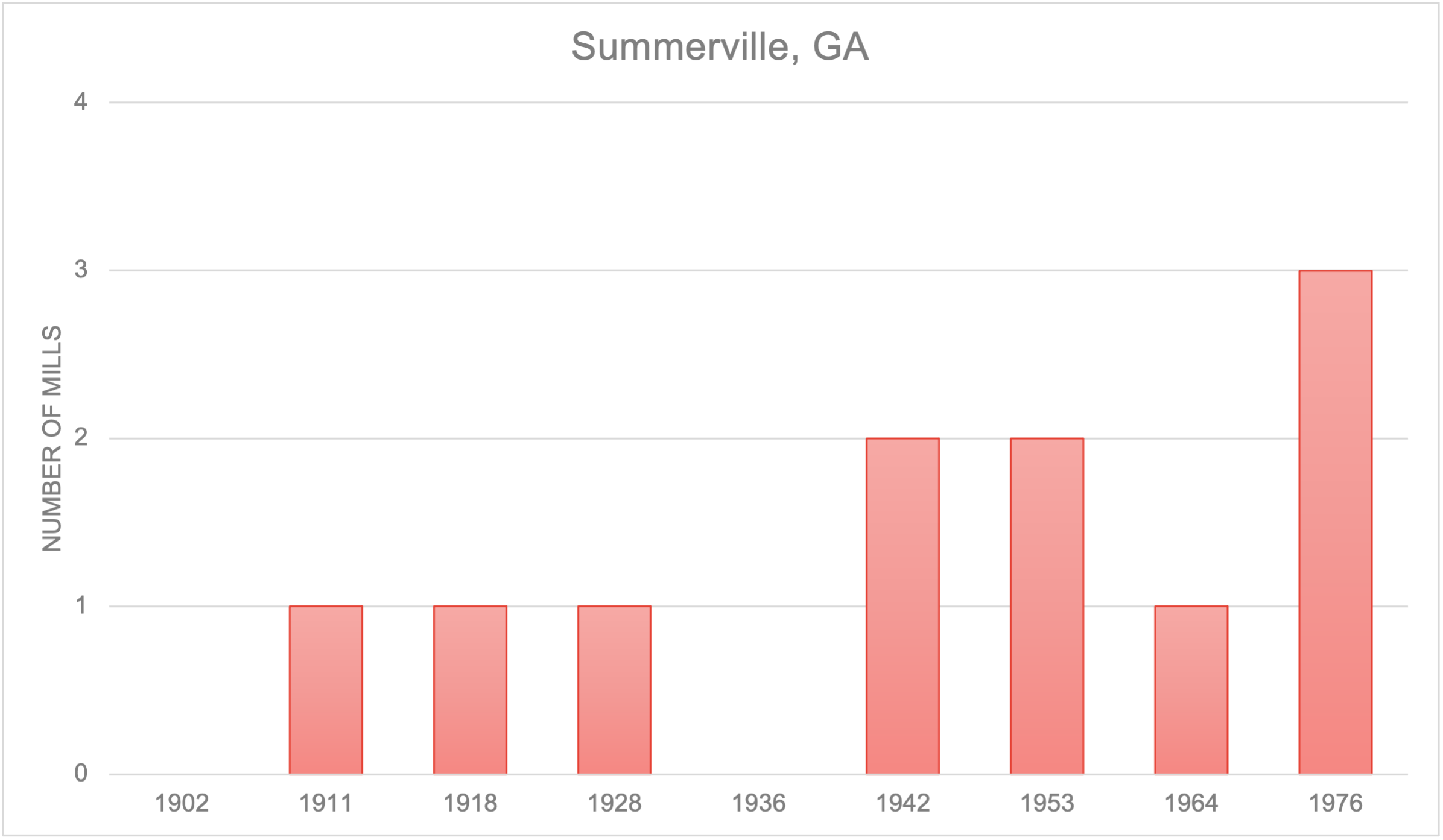

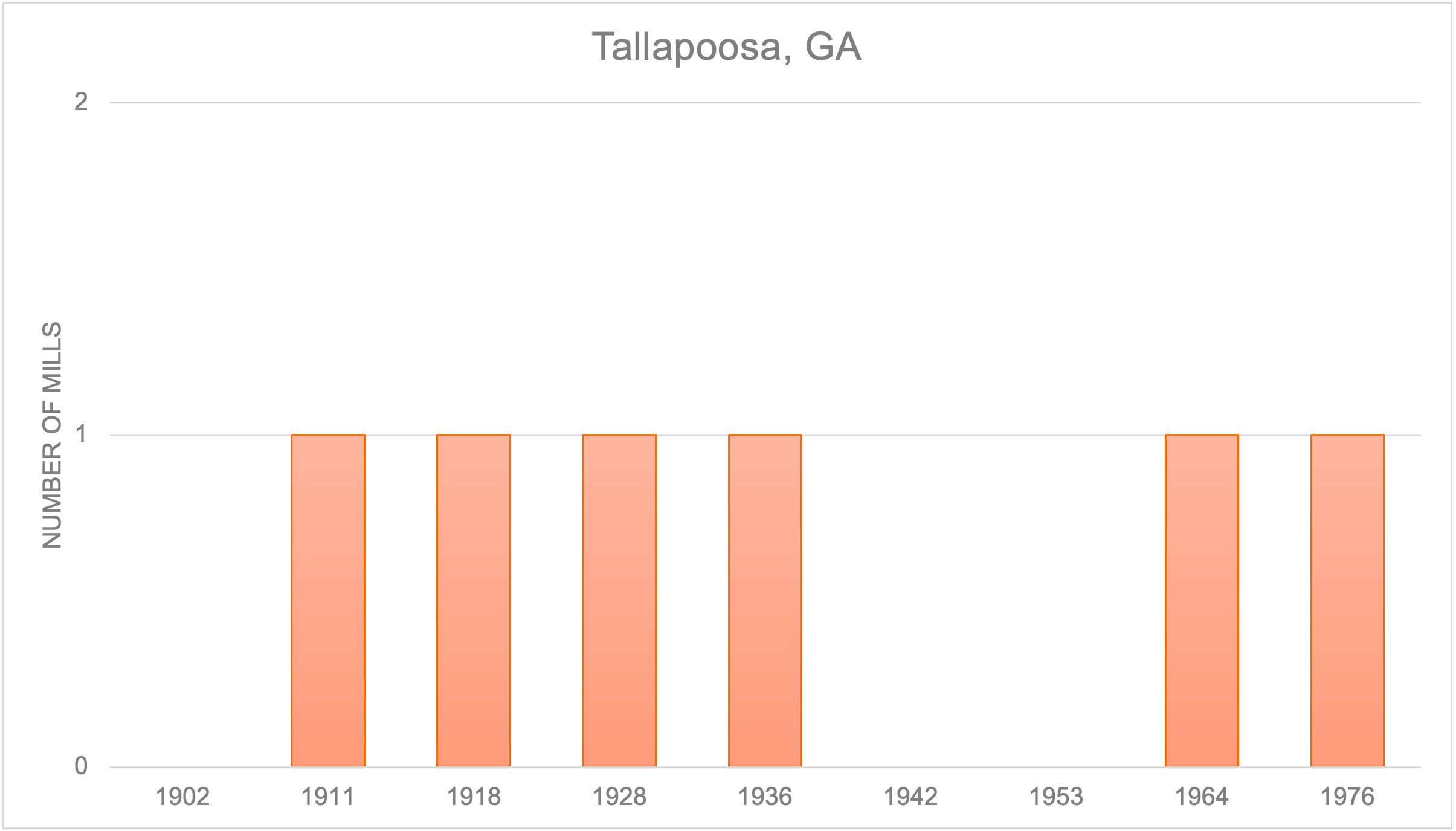

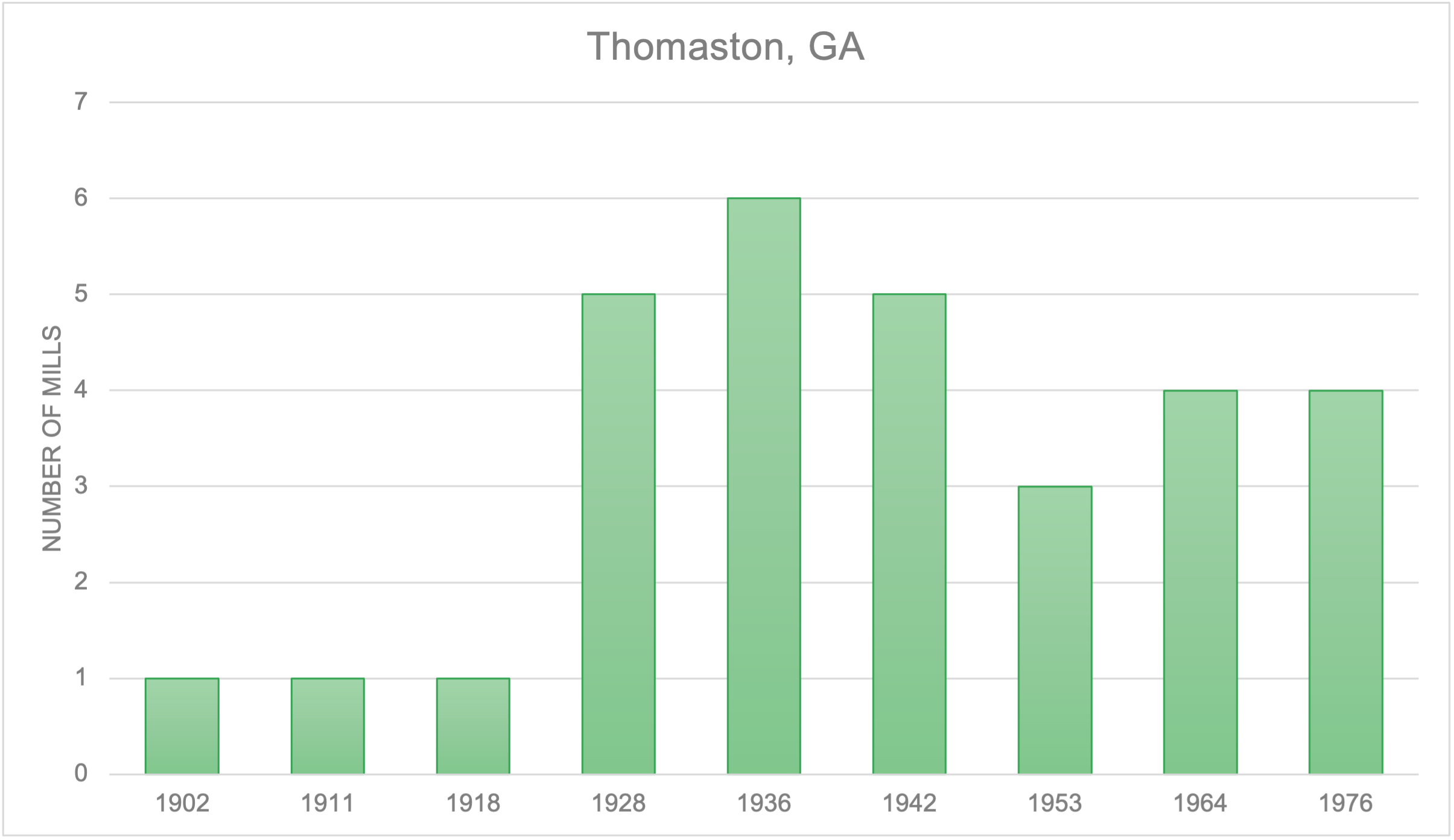

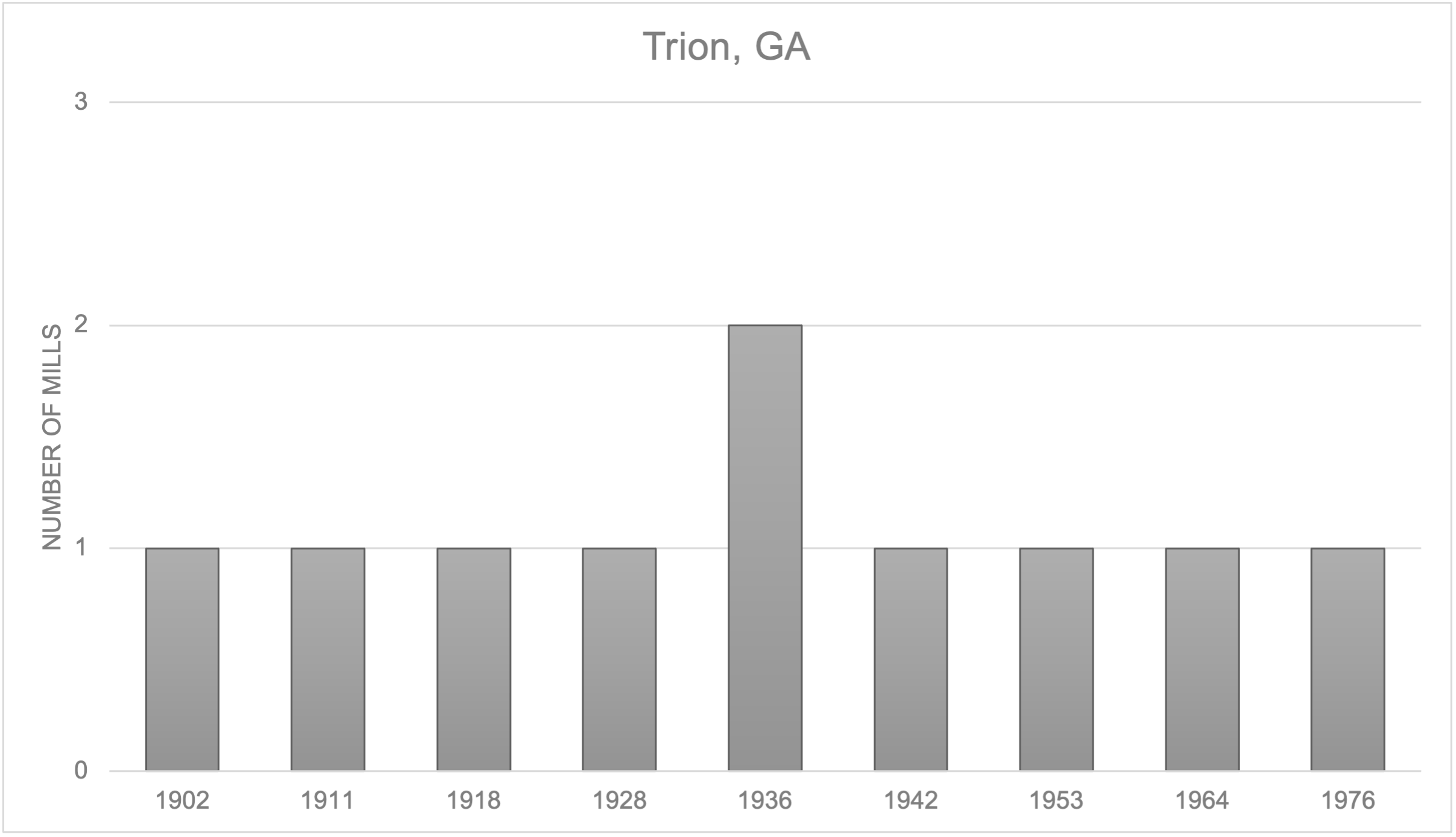

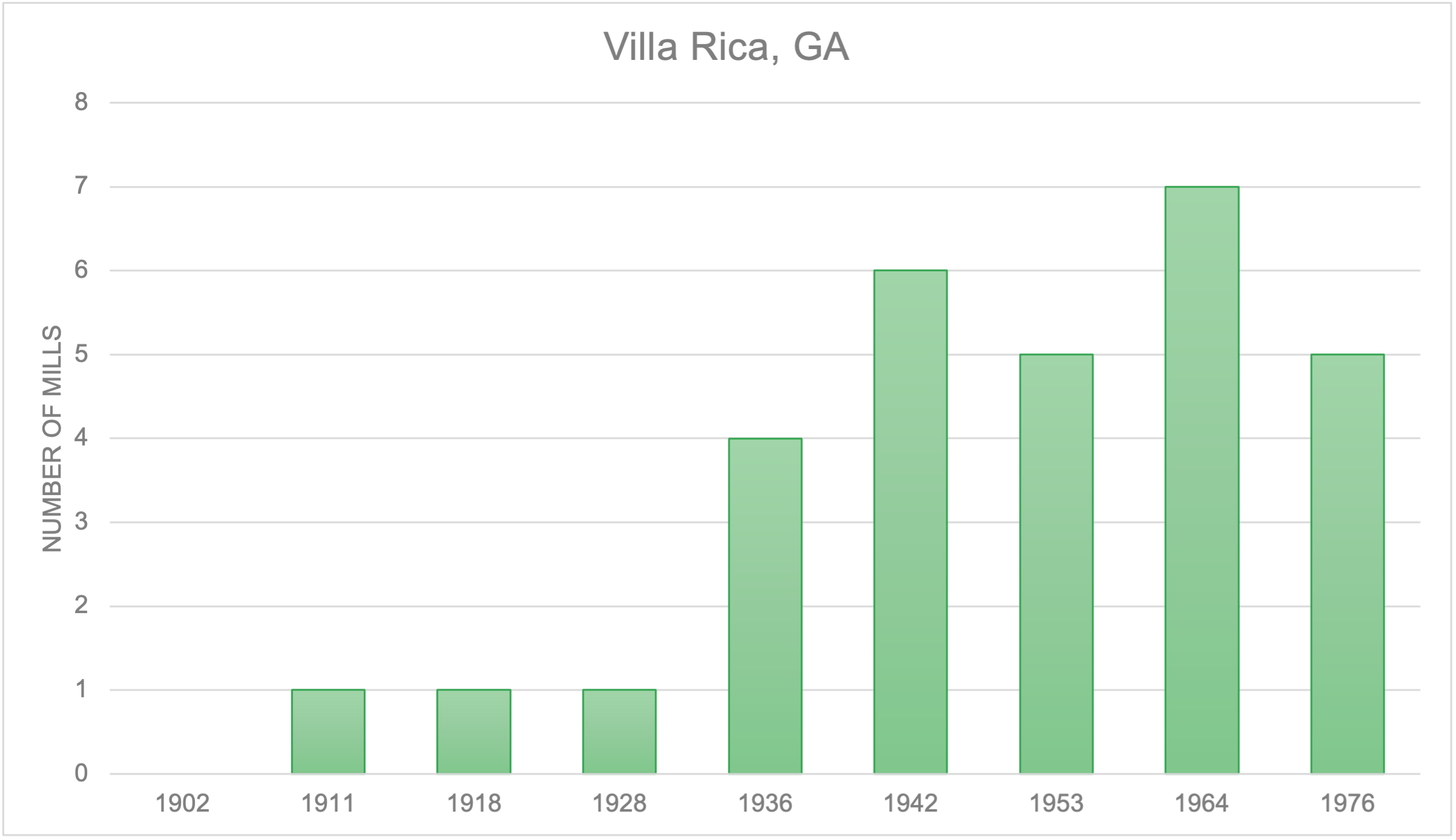

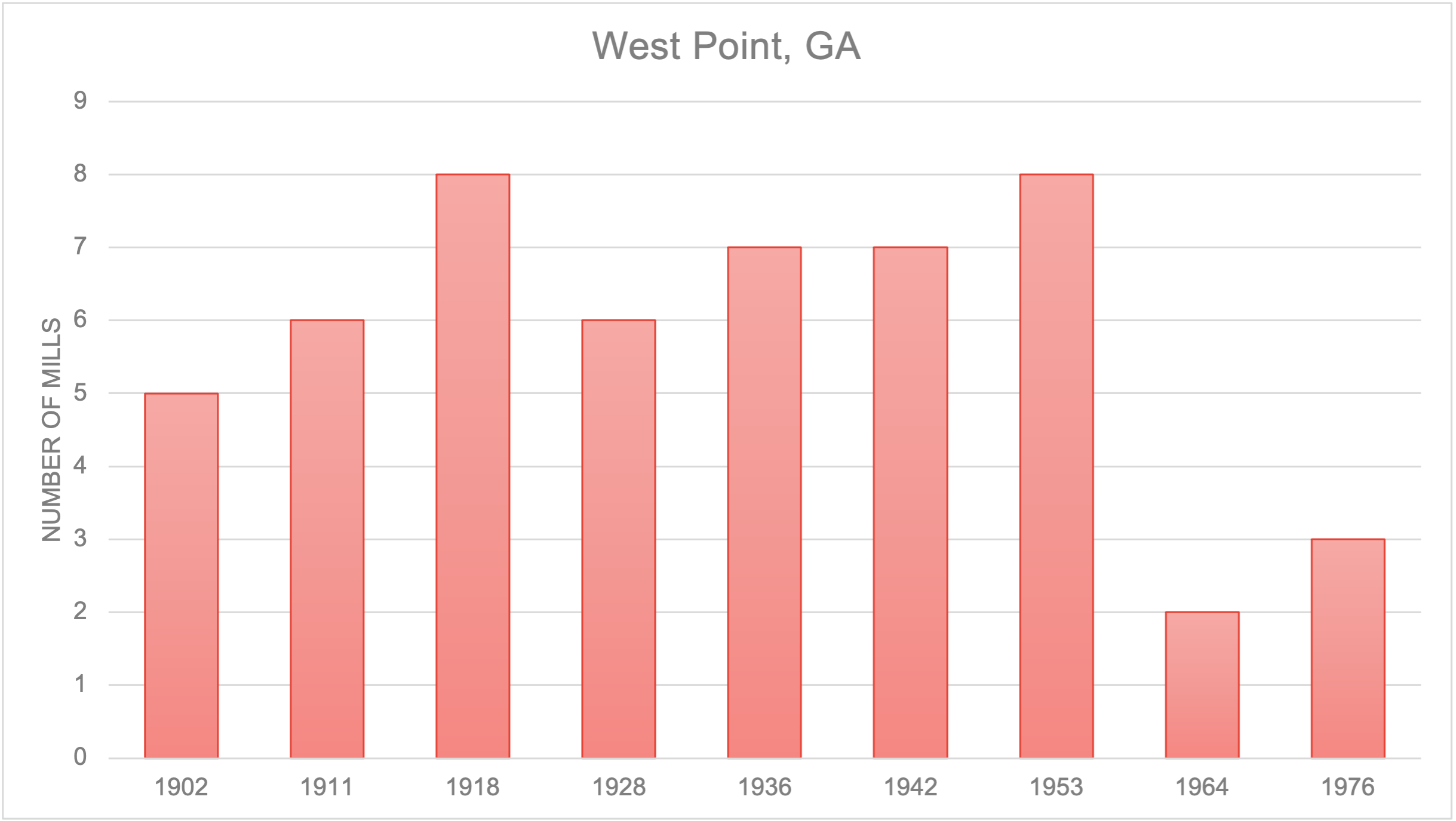

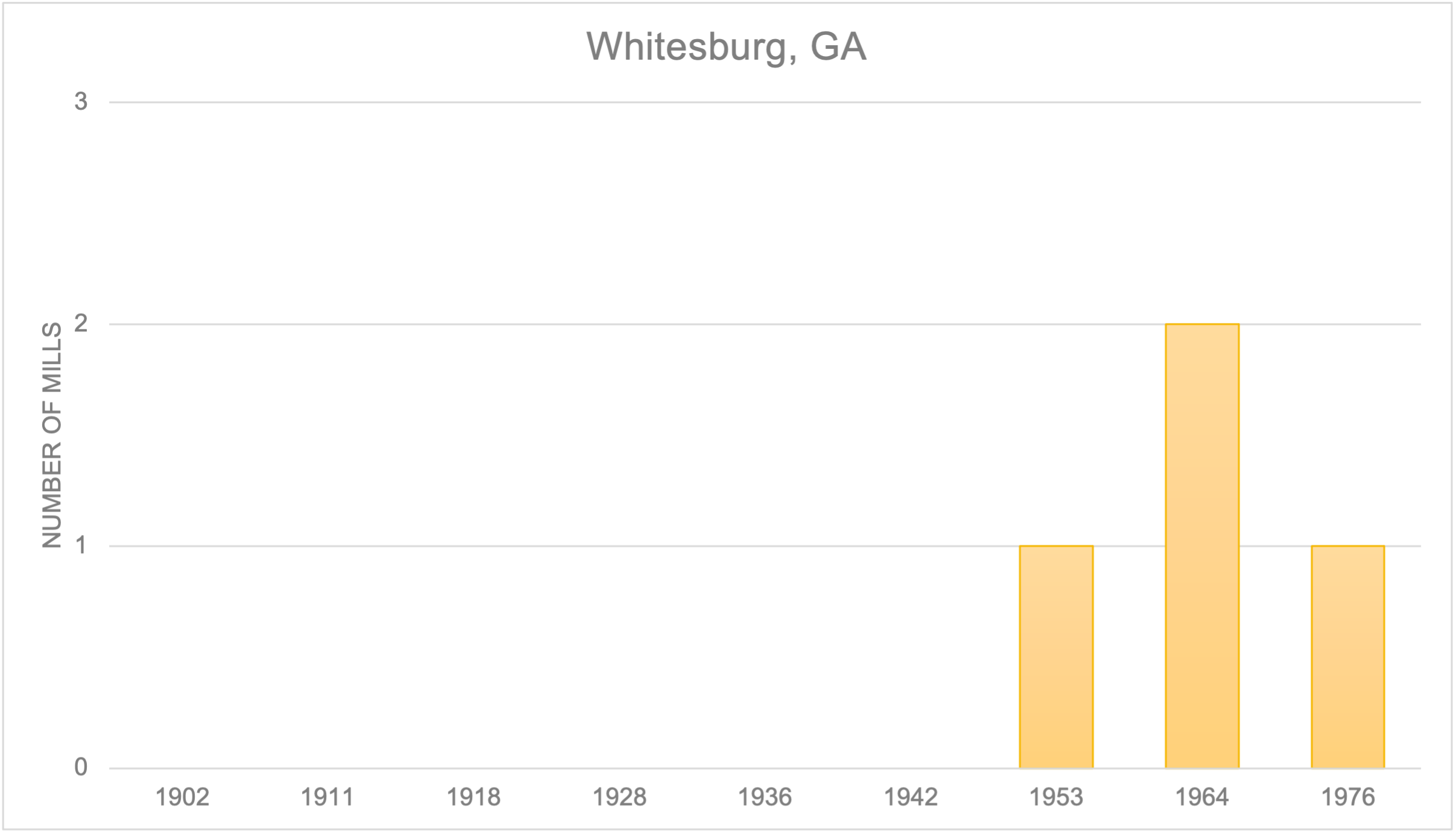

In the Spring of 2022, I commenced my work in the West Georgia Textile Heritage Trail project with the guidance of Dr. Andy Walter, Dr. Ann McCleary and Keri Adams. I began with making visual representations of the number of mills throughout the years of 1870 to 1976 of a few of the communities within the region of West Georgia and eventually made graphs of each community represented. These visual representations were in the form of bar graphs and culminated into a 3-D model graph which portrayed the number of mills throughout the years and compared them to all other communities within the research region.

It is amazing to see a visual rendition of the dataset as it portrays the history of the textile mills in West Georgia. It is interesting to see the decline of textile mills that some communities have experienced and the increase that others have gone through. What would be fascinating to see is the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of the cities compared to the number of textile mills throughout the years and if there is a correlation between GDP and number of textile mills. Another worthwhile project to undertake would be the representation of women owned textile mills in West Georgia, if there is any, and their stories.

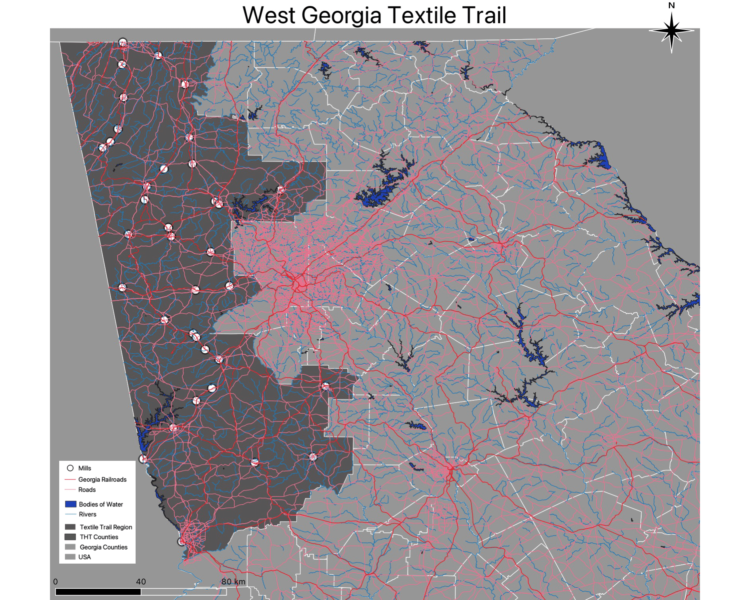

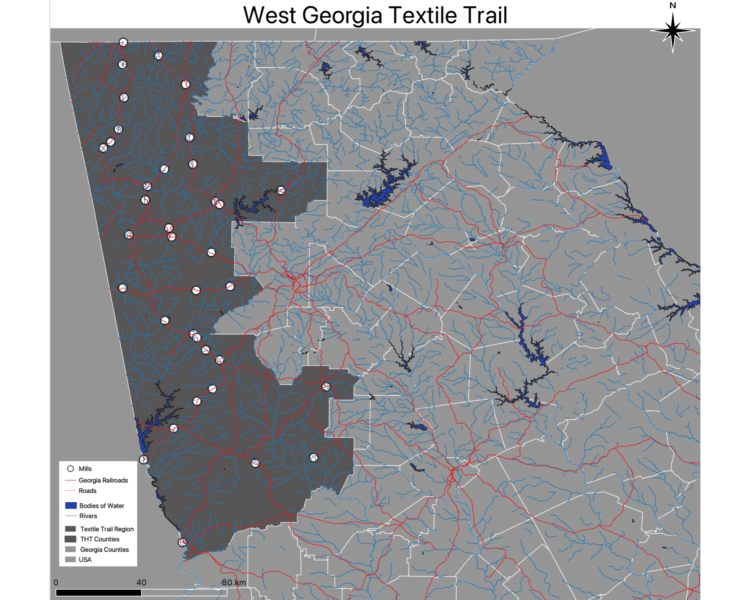

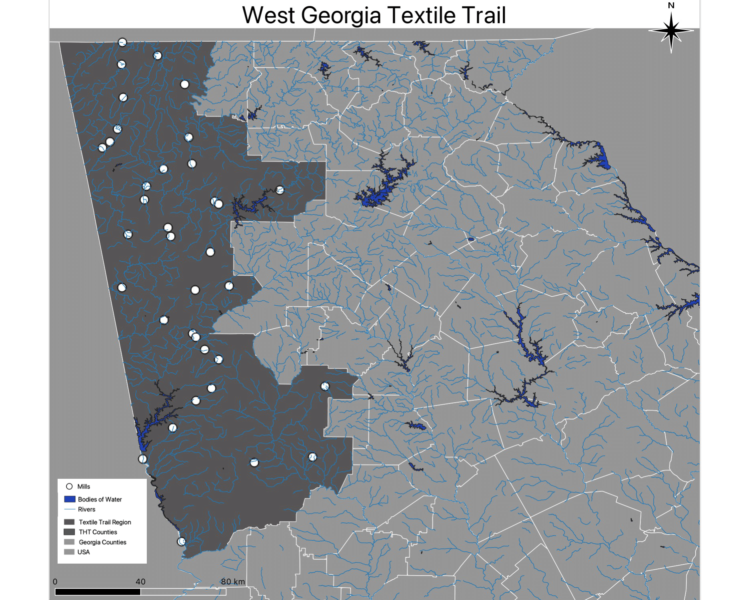

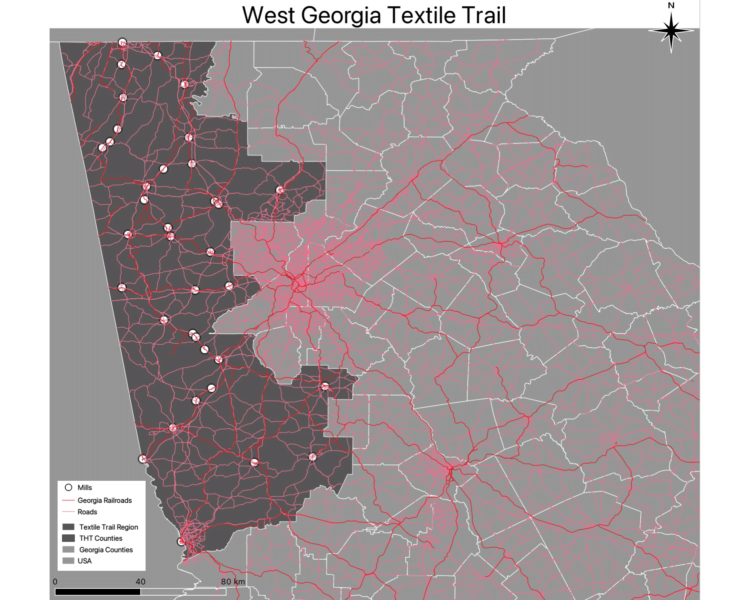

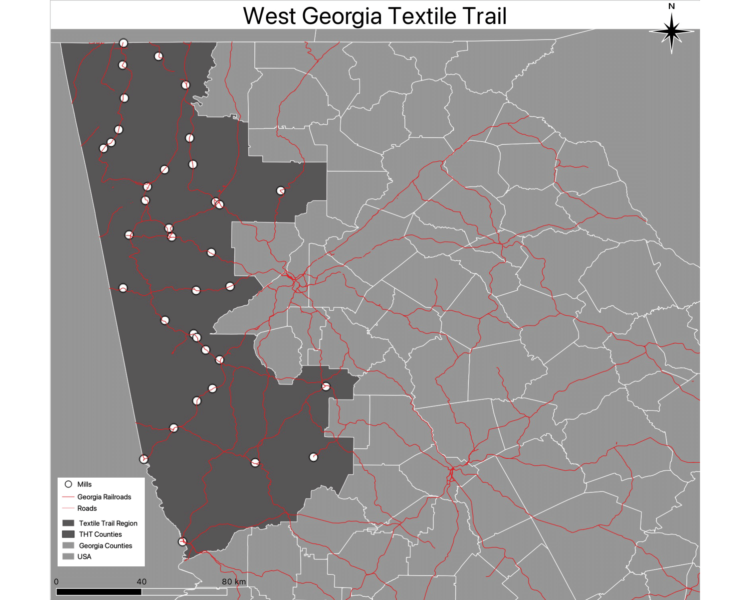

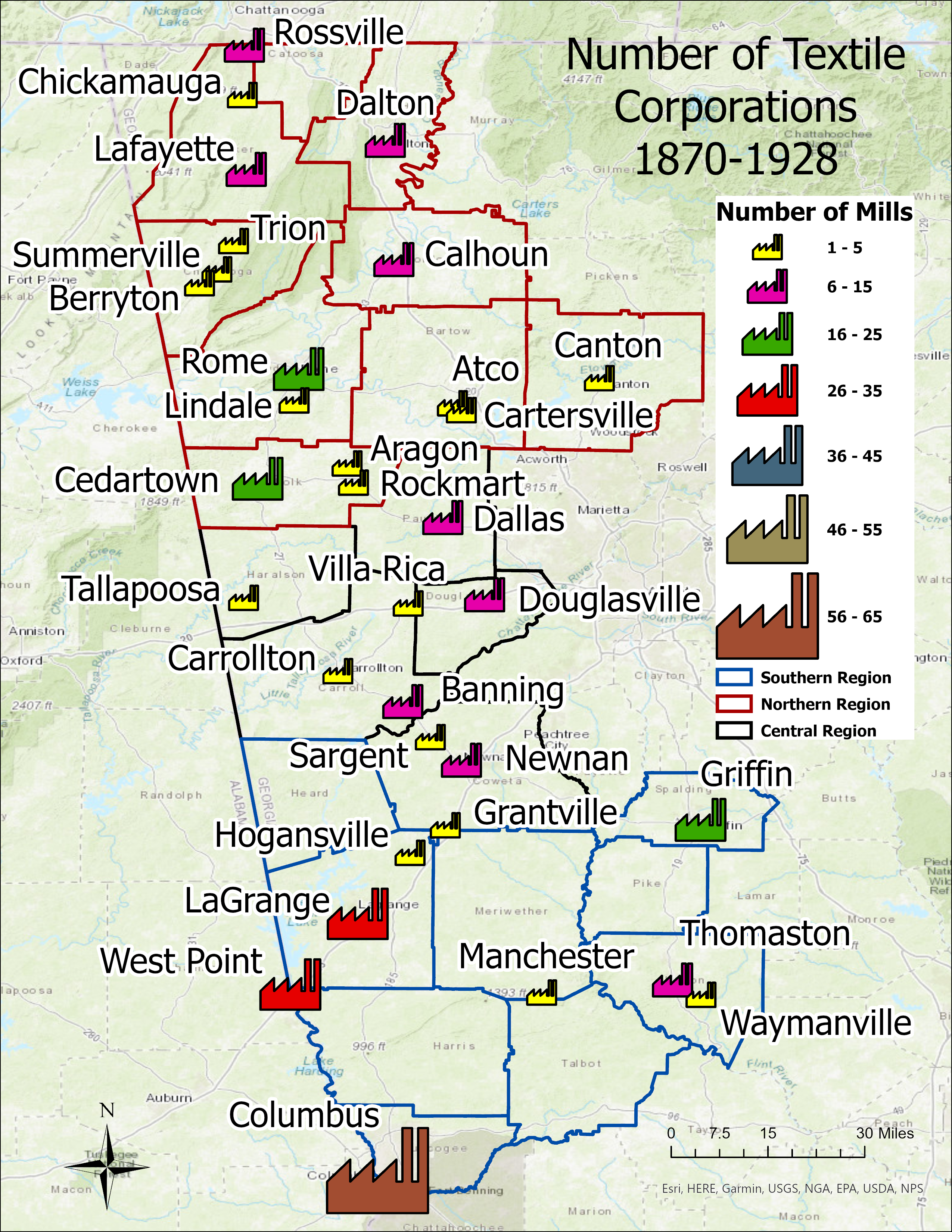

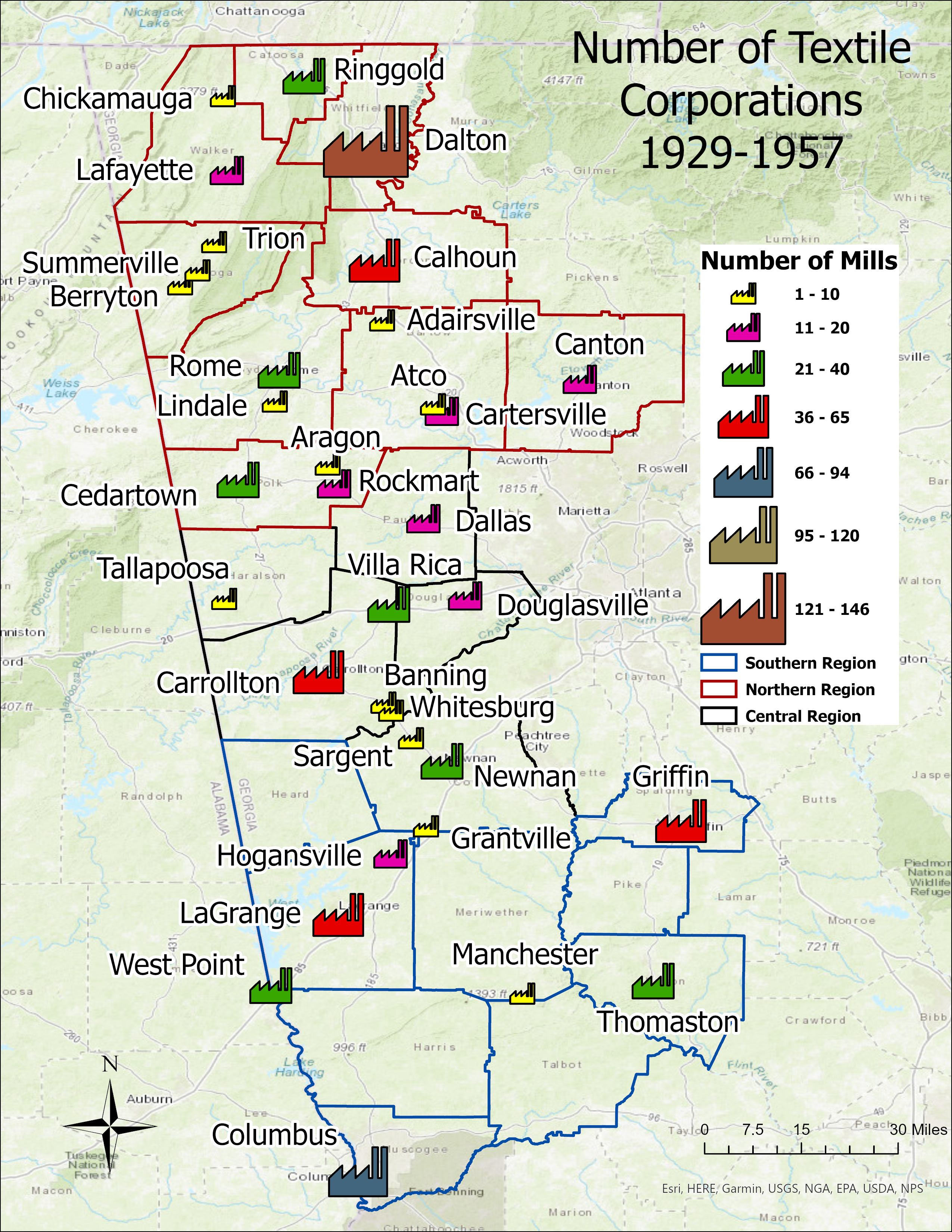

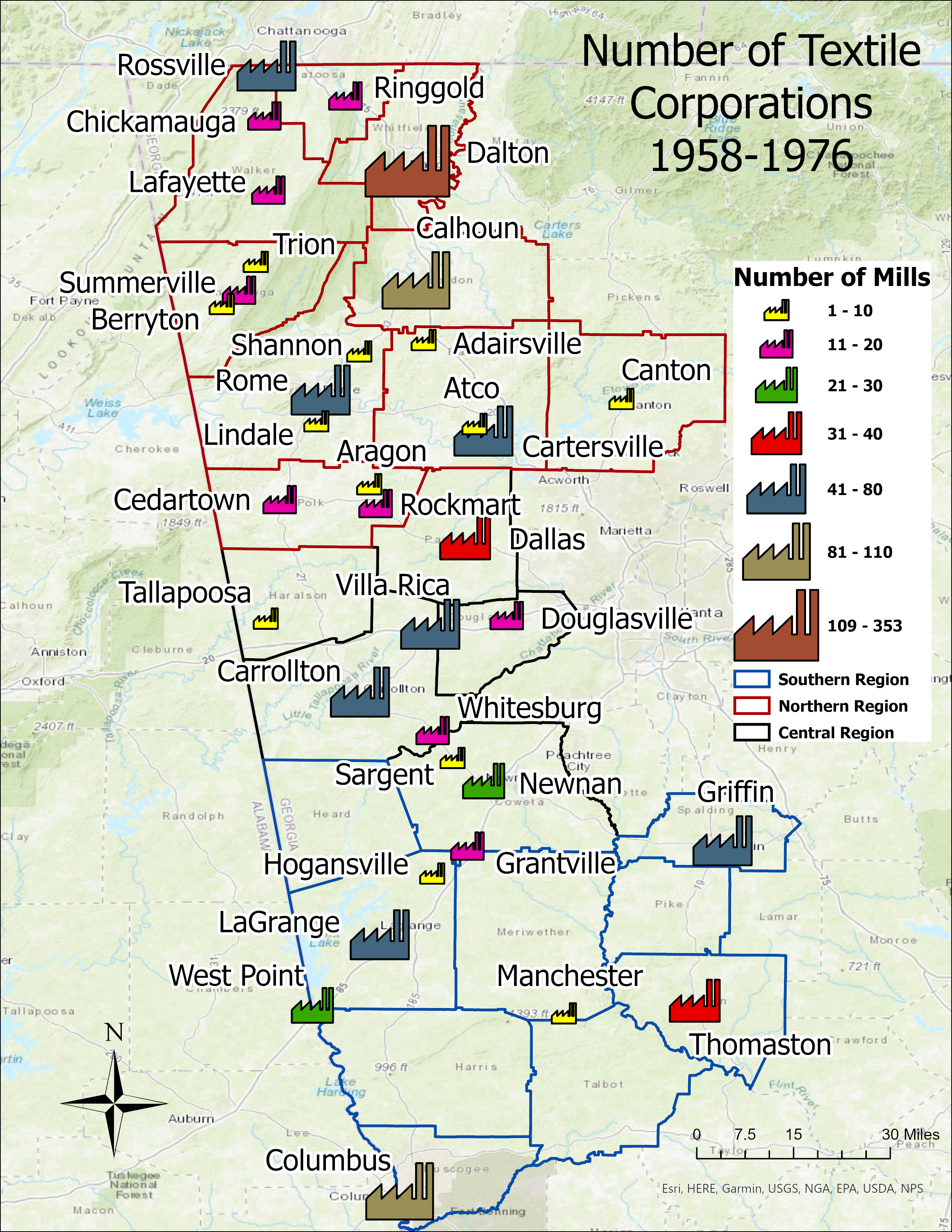

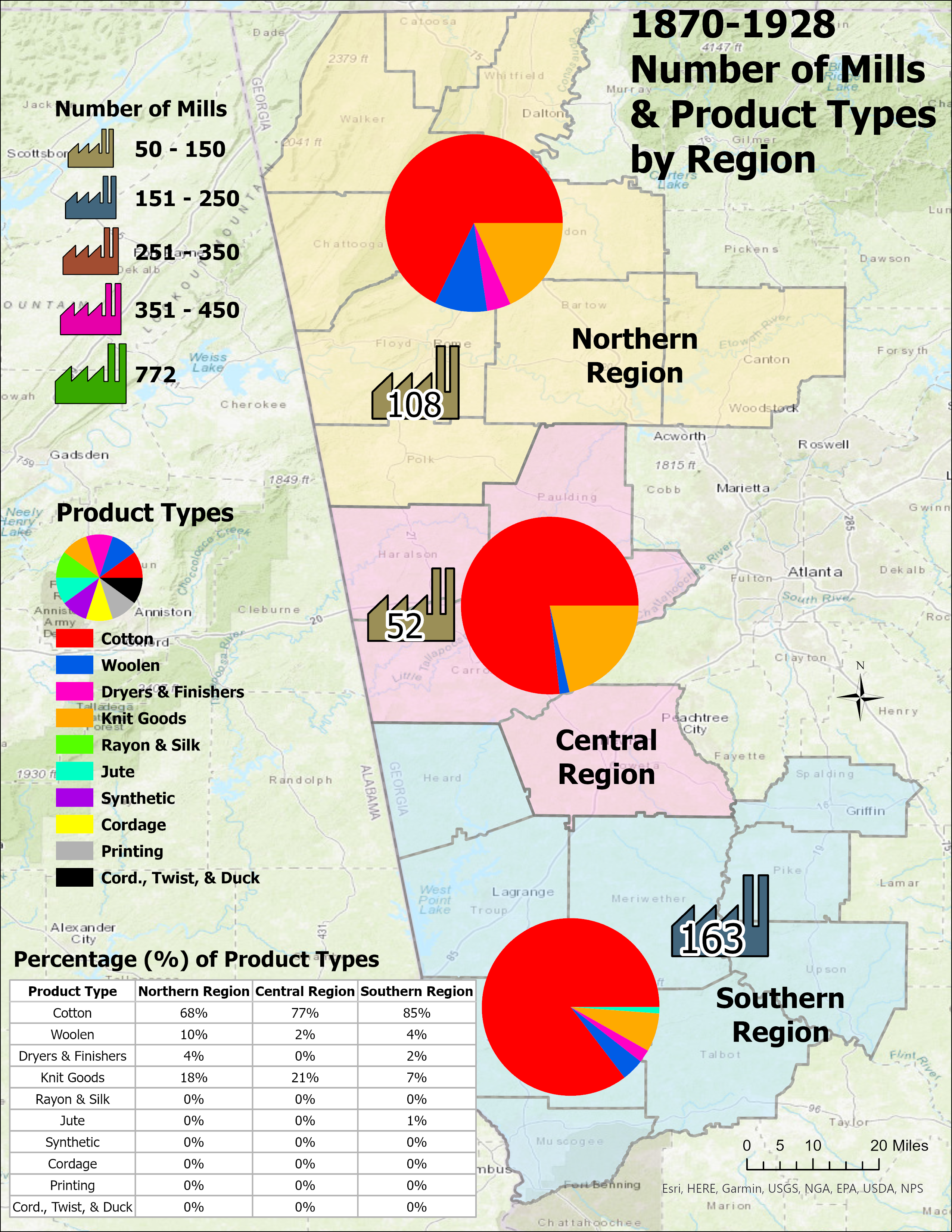

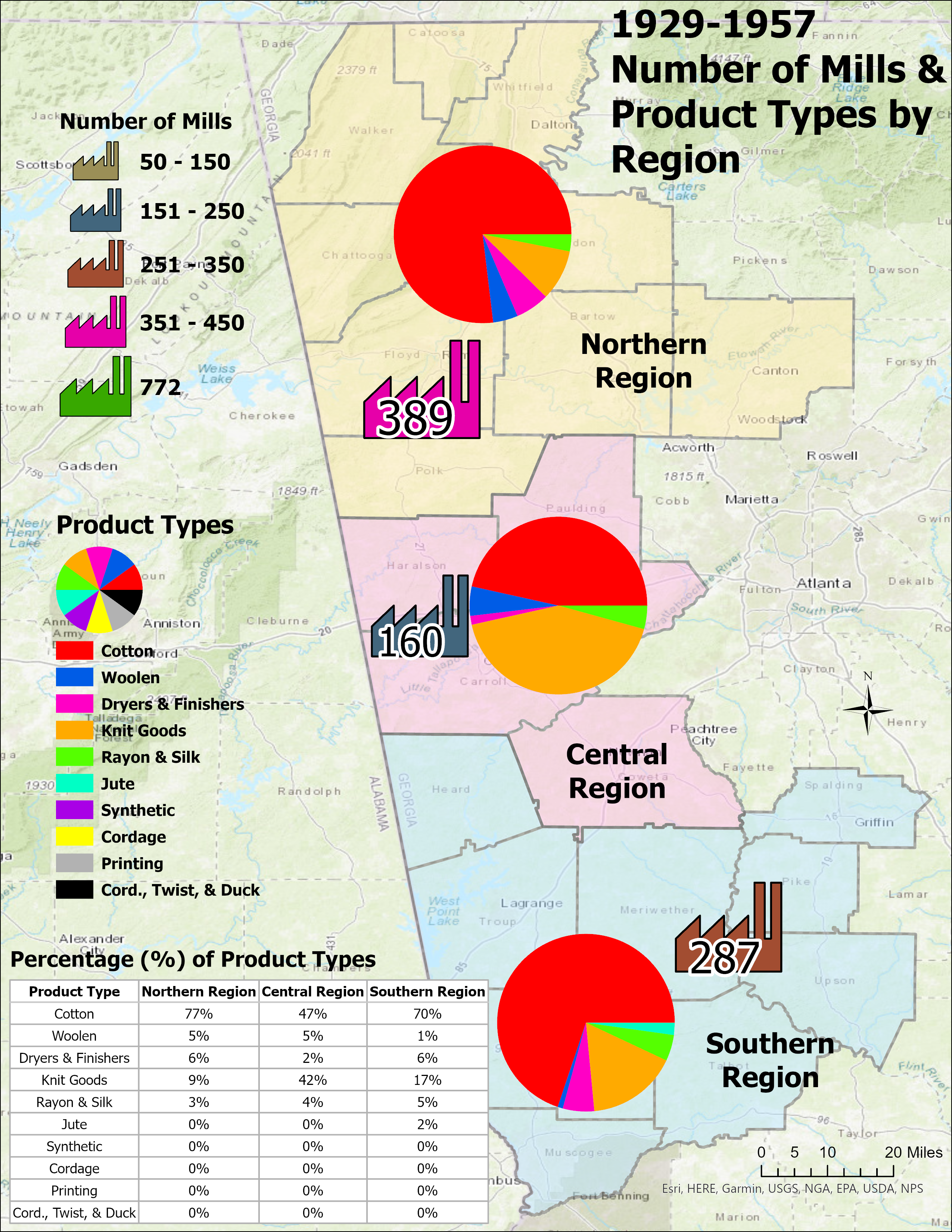

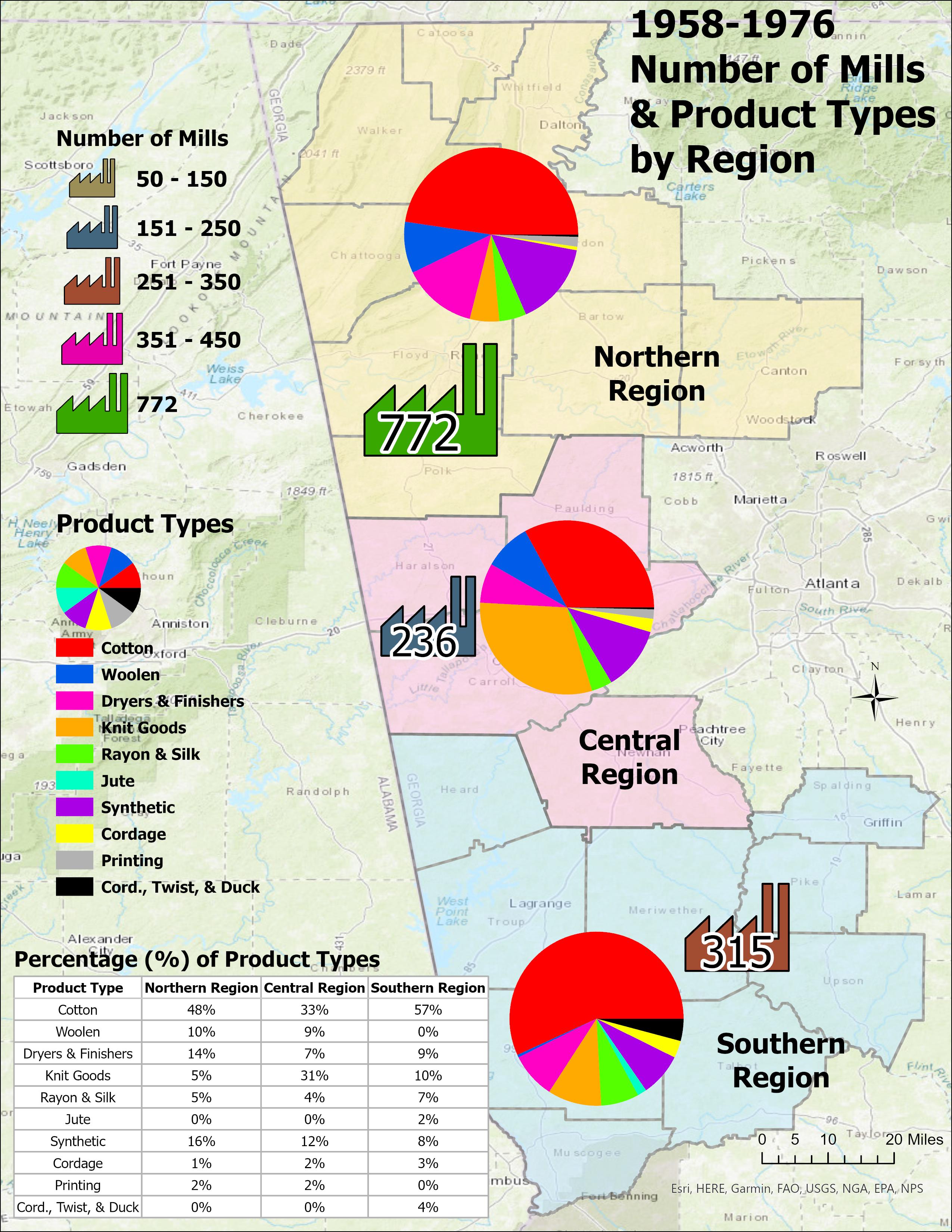

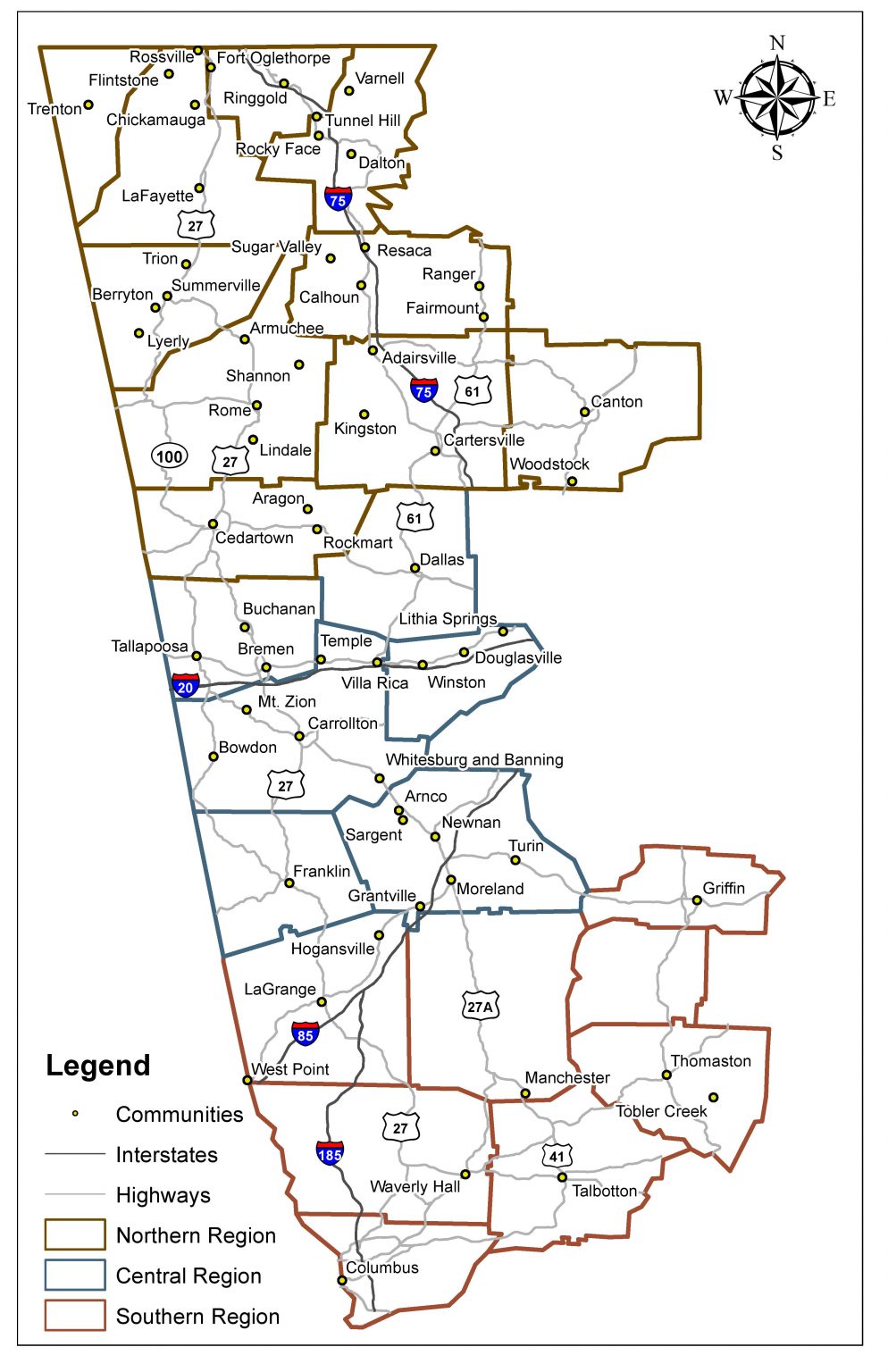

As the semester progressed, I started mapping out the West Georgia region using Quantum GIS (QGIS). QGIS is a free to use and open source mapping software that offers a wide range of data editing and mapping features. This allowed me to learn more about the program and I delved into refreshing my memory of mapping and QGIS as well as learning new things about the program and how to produce an end result that is both visually pleasing as well as easy to read and understand. When making a map, or any other visual representation of data, one must always keep in mind the viewing audience and cater to them, making it intriguing, informative, and readable. Throughout my time spent graphing, mapping and collaborating with others, I was able to learn so many valuable skills that I will take with me for my future professional endeavors.

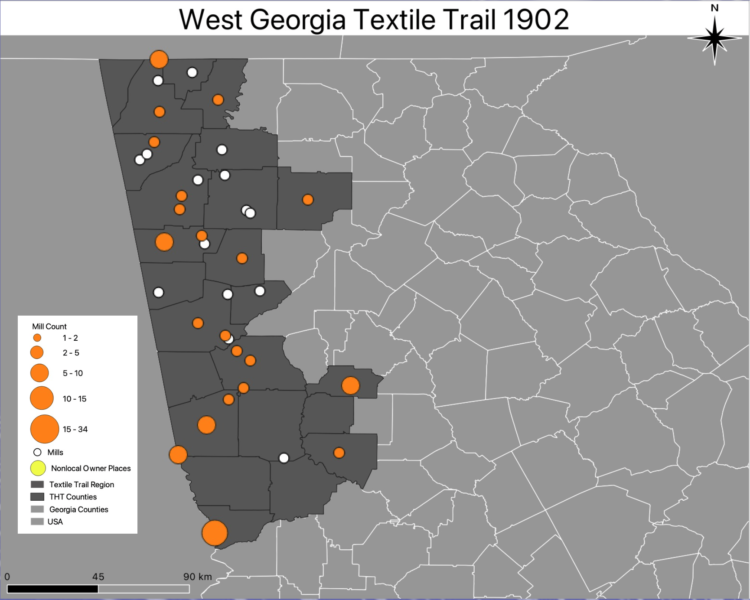

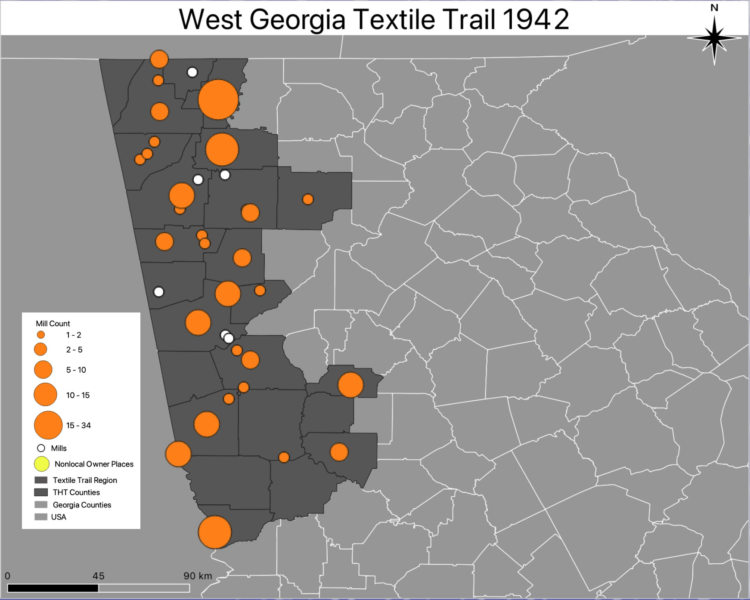

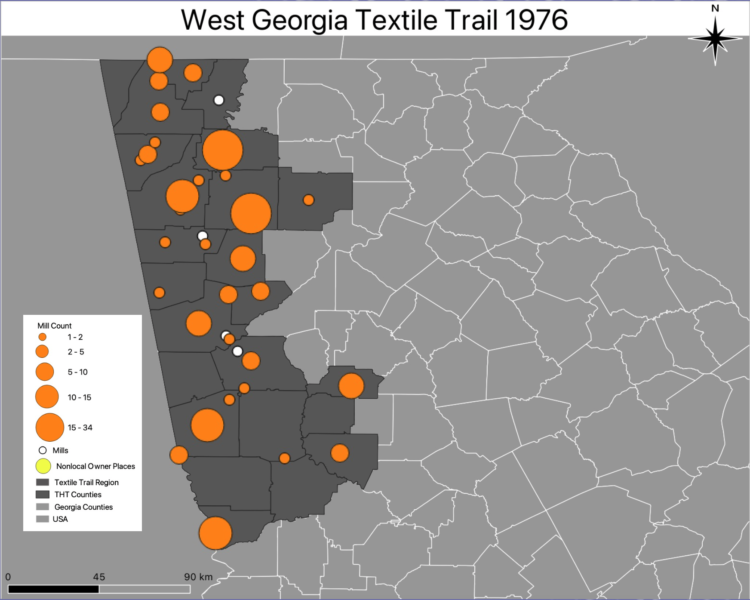

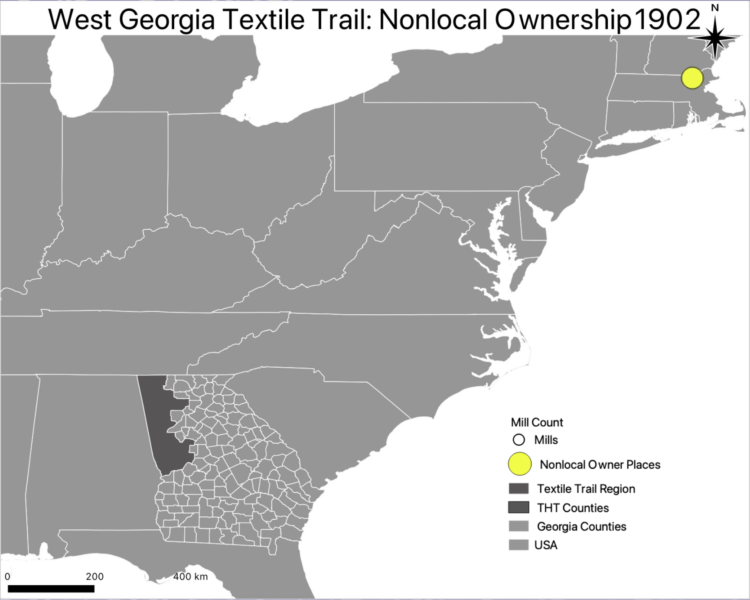

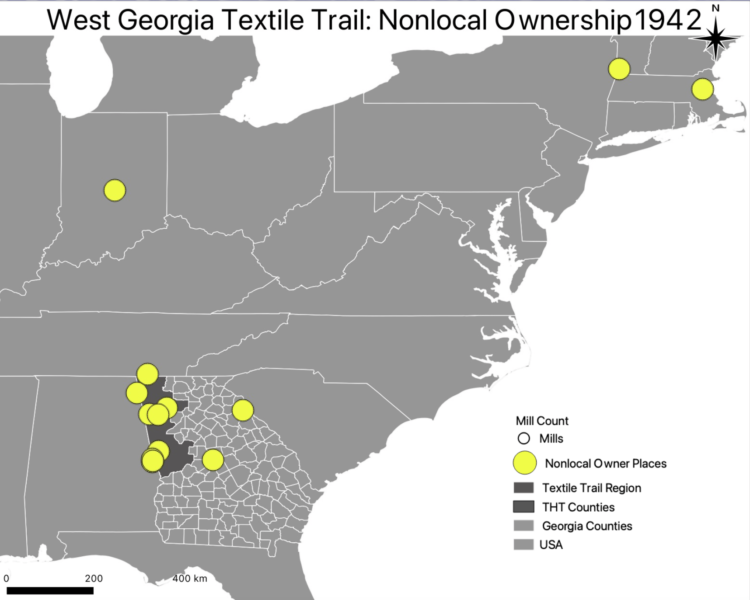

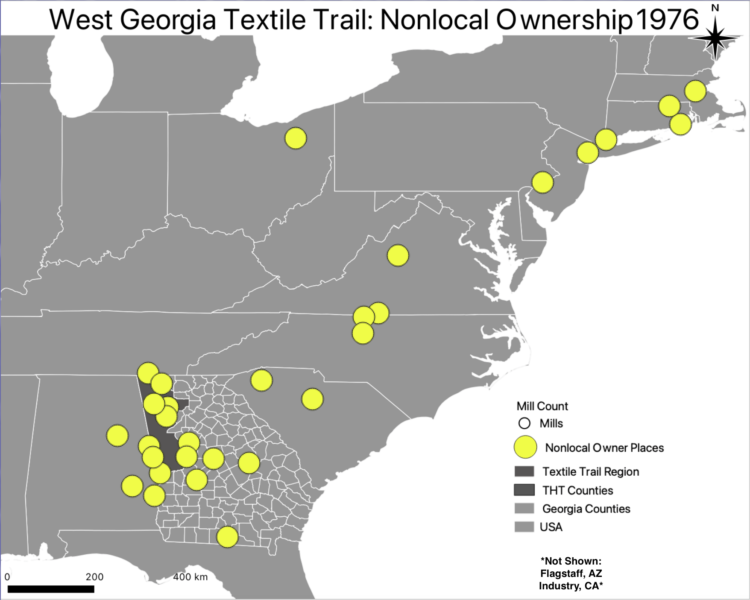

All of my work throughout the semester culminated into the Scholars’ Day end results seen below. Scholars’ Day is sponsored by the Honors College and the Office of Undergraduate Research. It is a day in which undergraduate students present their research projects in the form of an oral presentation, poster presentation (which is what I did), visual arts presentation, or a performance presentation. It tells the story of the economic flow of the West Georgia textile industry. As we can see, nonlocal investment steadily increased throughout the years, first seen with the nonlocal ownership in Massachusetts. This then spread to regions on the east coast but there were even nonlocal investments in both California and Arizona in later years. It is amazing to see the changes throughout the years and how it has shaped these communities into what they are today.

Scholars’ Day was a great experience as I was able to put my presentation skills on display. Of course I was nervous at first but after presenting my project over and over again, I was able to lose my nervousness and perfect my presentation along the way. This was great exposure for my future endeavors and I truly did learn from my experience at Scholars’ day. There were some great suggestions from the audience at Scholars’ day, one of which resonated with me. Someone in the nursing profession suggested seeing the correlation of cancer rates within these communities compared to others that are not around textile mills. This could be a possible project undertaken in the coming semester or in the future.

Slideshow of Maps:

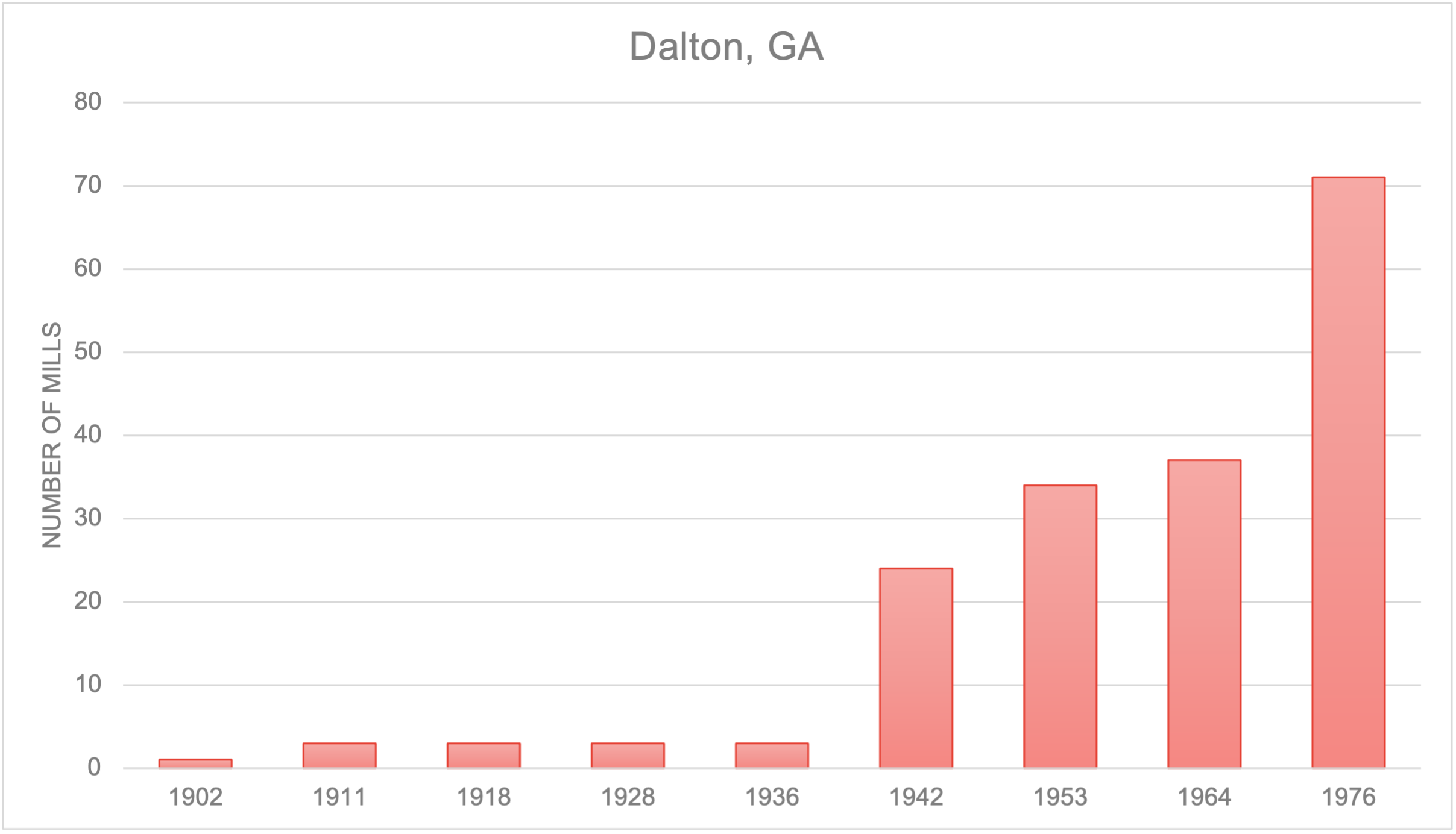

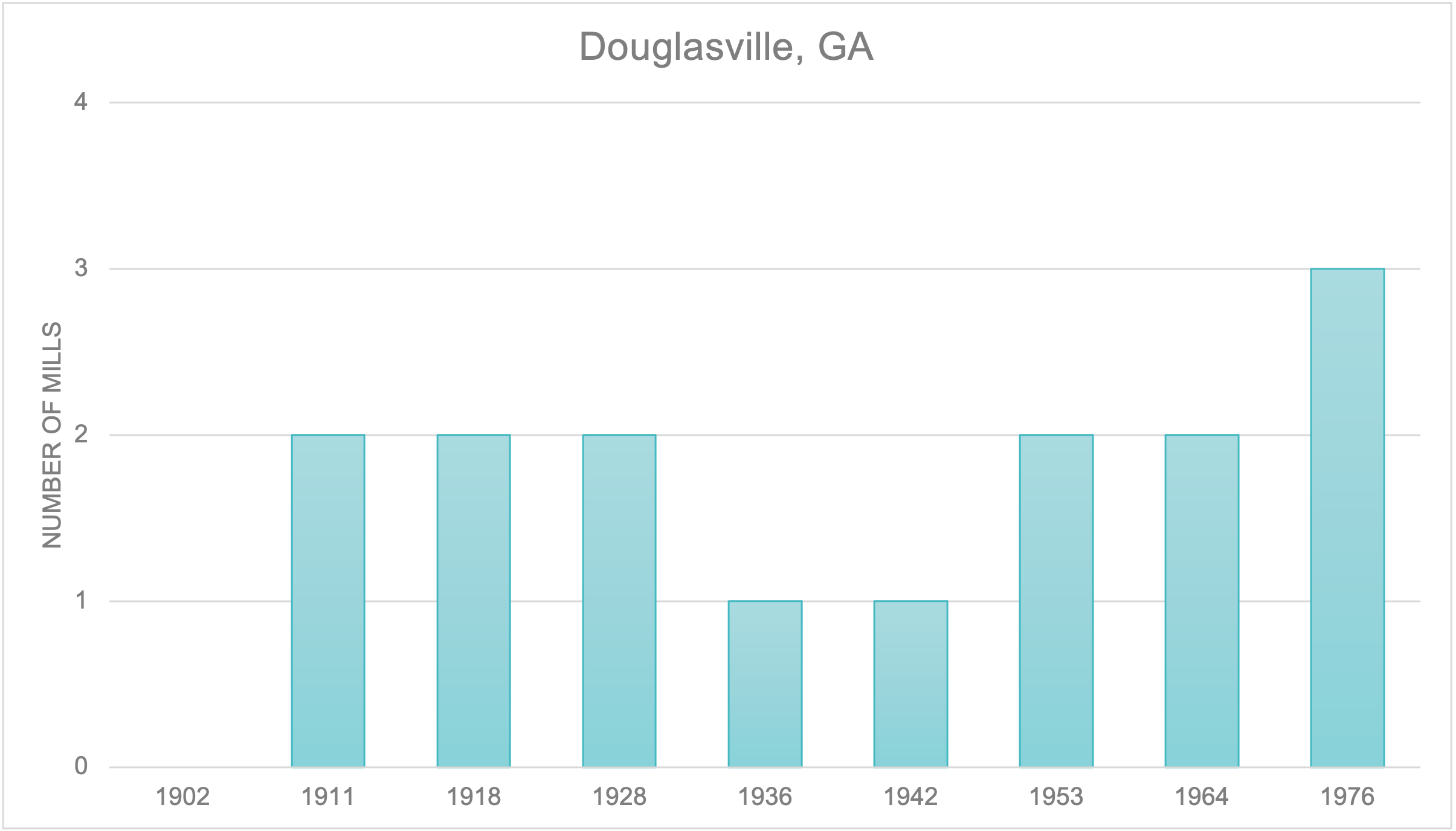

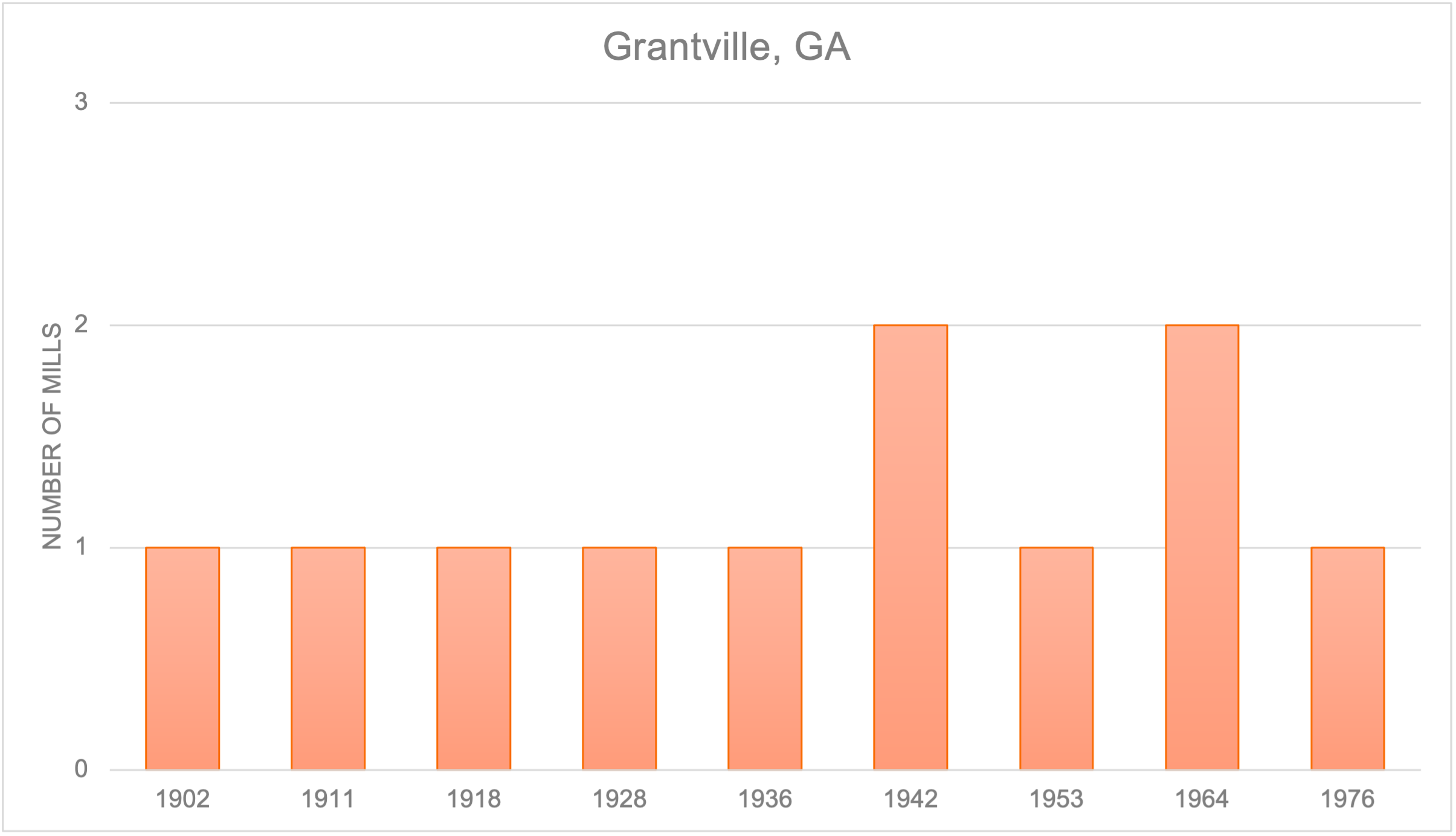

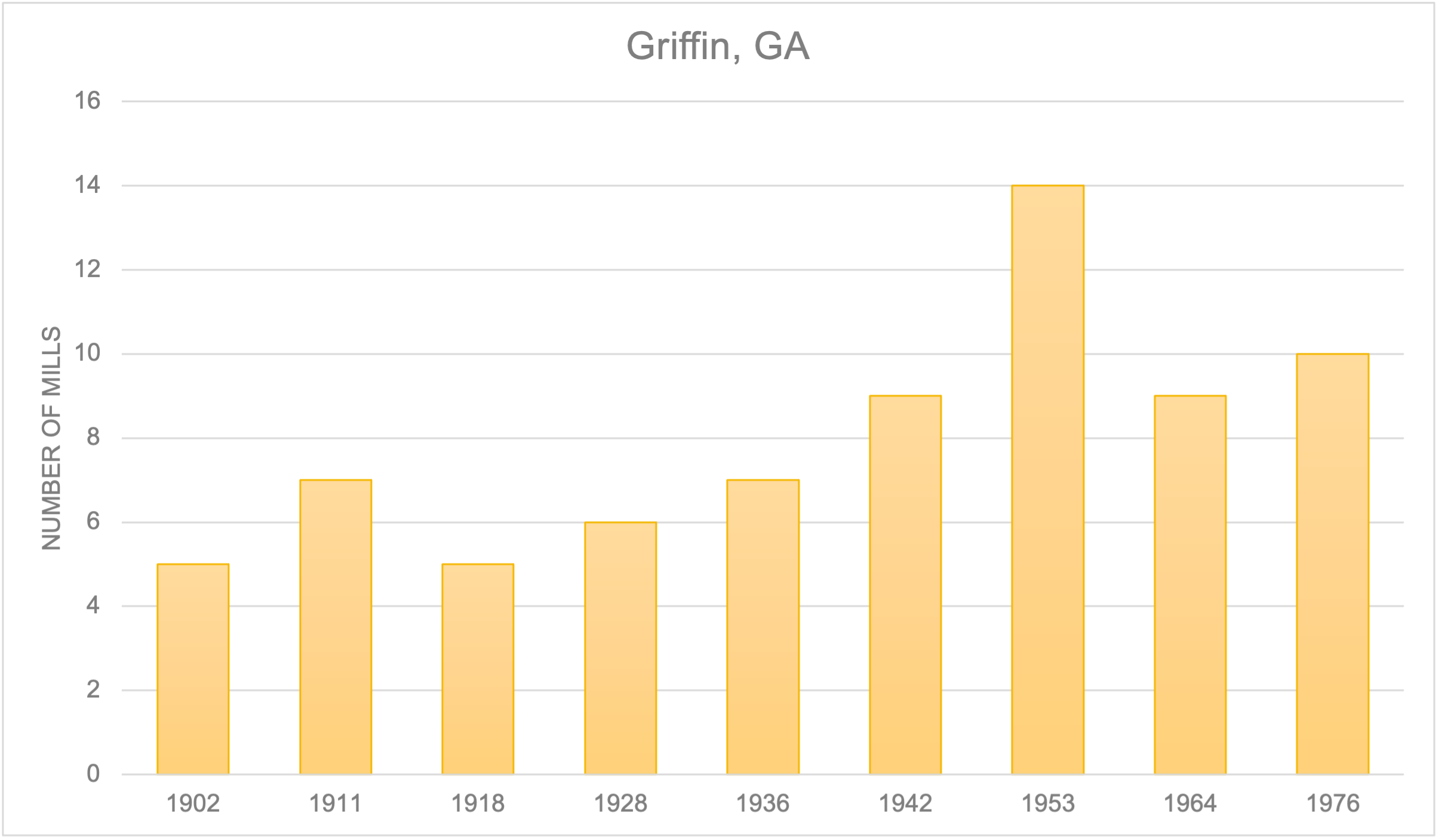

These graphs were very enlightening and show how visual representation can contribute so much to understanding a topic. They are also very easy to read and understand so that it reaches a wider range of audience. While making these graphs, I noticed several trends, one of which is an increase in mills in some of the cities such as Dalton, GA and Calhoun, GA. It can also be seen that some communities have remained consistent with the number of mills throughout the years as well as a decrease in the number of mills in other communities.

It’s amazing to see all this information side by side, year by year and comparing how the mills have increased, decreased, or remained constant in communities over time. With the help of some more research, these graphs can be further developed to provide a more detailed depiction of the fluctuation of the number of mills within these communities throughout West Georgia and how it has affected them. Collaboration with these communities is an essential part of accurately portraying the stories told by these graphs. The graphs are only a small portion of the full story.

Slideshow of Graphs: