Author: Tinaye Gibbons

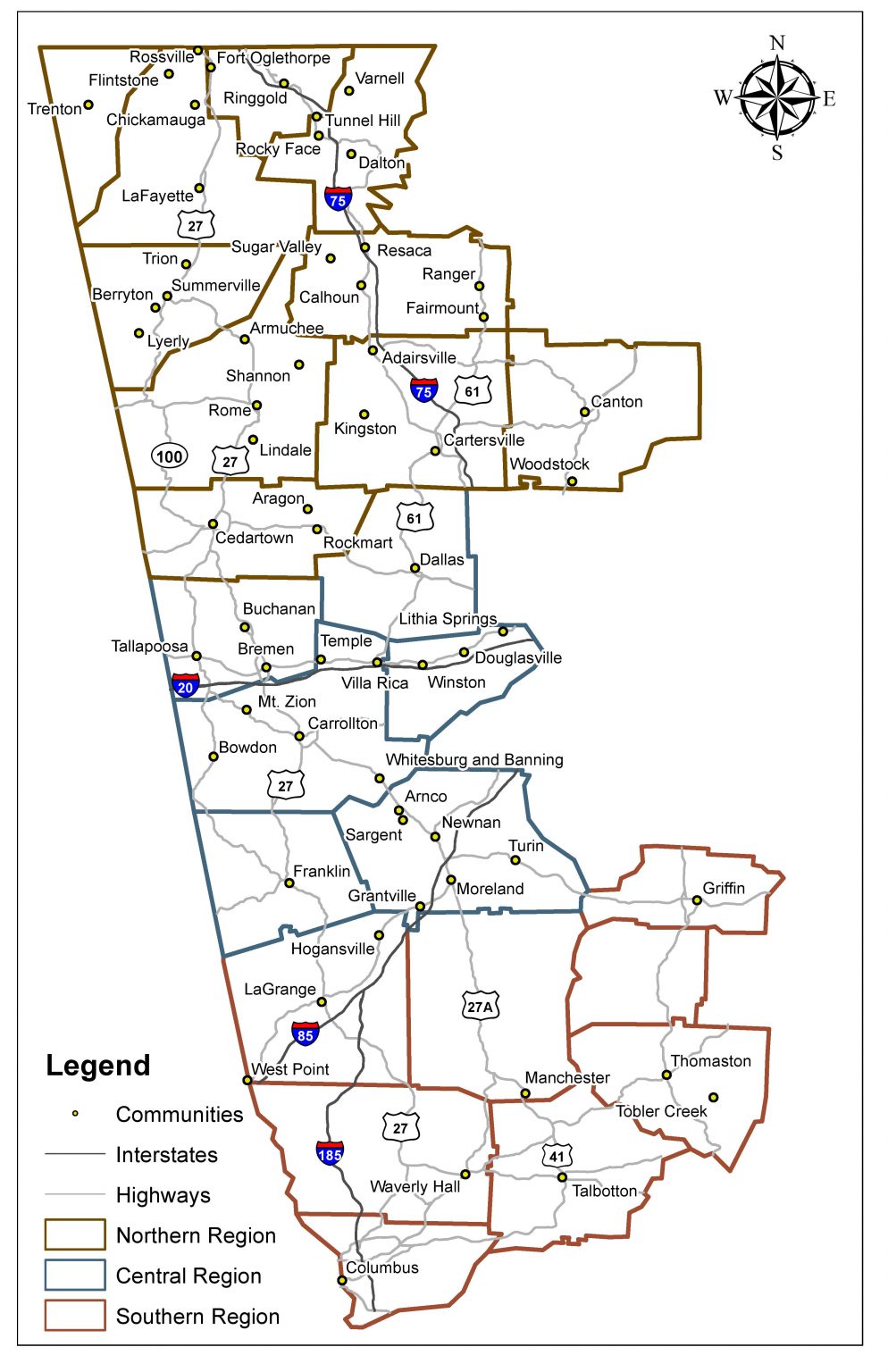

Textile history is important to us at the Center for Public History because of the diverse ways that it impacted communities across West Georgia specifically. We analyze and study the communities along our trail because of the influence and impact that the textile industry brought to and had on the area and region. Many of the people in these communities worked in, for, or somehow with the textile industry throughout the twentieth century. We have researched this history in these communities by analyzing the mills which were there, as cities had everything from cotton mills to chenille bedspreads, but all of them supported a workforce and sustained local communities throughout Georgia. This spring, we had an undergraduate research assistant who assisted us in researching these communities in a new way. She used Sanborn Maps to study textile mills in these areas.

The Sanborn Map Company was founded in 1867 in Pelham, New York, by D.A. Sanborn. Originally, these maps were created as fire insurance maps, so that businesses or residences, could be correctly identified and properly cataloged by fire marshals if disaster struck. 12,000 cities across Mexico and North America were documented and mapped out annually. Sanborn maps are incredibly useful as research sources because the collection of maps shows the change in industry over time by examining building additions, new mill structures, and mill homes, and the use of buildings by titles and names from year to year.

Center undergraduate assistant Tinaye Gibbons spent the spring semester of 2018 looking at each available Sanborn map of communities along the Trail. The Sanborn maps allowed Tinaye to analyze the change in the built environment of cities as textile mills grew and expanded throughout each community that we had maps for. Some of these communities – Dalton and Columbus especially – had sixty or seventy maps whereas less industrial places had fewer. The majority of her work was focused around Dalton and Columbus, Georgia, as they were heavily documented by Sanborn Maps due to the amount of textile industry each city had. Columbus’s economy was driven by textiles, and most of the mills were cotton-based. Muscogee Manufacturing Company, for example, employed 650 people in 1910 and manufactured denim, towels, and even couch covers.

Tinaye noted in her research that, “not every community on the Textile Heritage Trail had Sanborns created, but the majority of cities that were present did allow me to look at a wide range of textile industries.” Dalton, Georgia, similar to Columbus, also had an economy that was strengthened by the textile industry in the city. The diversity of textile mills throughout Dalton is evident in Sanborn maps, as the textile industry grew throughout the city. The carpet manufacturing was the longest operating mills in Dalton. Chenille bedspreads, hosiery mills, and carpet production all fueled Dalton’s economy in addition to the cotton mills.

These maps documented local history as well, due to their ability of showing how the city was changed by the textile industry growth and decline. Sanborn maps helped to document change in the city as new mills opened, closed, and new businesses took over mill spaces as they closed down over time. The textile industry fueled the economy for many of these cities. As textile mills continued to thrive throughout the twentieth-century, cities adapted to the expansion of the mills that were there. As technology advanced, mills began to expand both in function and in size. Whereas mills used to just produce goods, now they were able to dye the fabrics in house, for example, and the Sanborn maps were great resources for documenting these changes as mill buildings showed up on different maps. The history of the city is evident in Sanborns as well as it shows how local businesses and city growth were impacted by the textile industry.

Tinaye was hired through UWG’s Student Research Assistant Program (SRAP) through the Honors College. This position meant that she needed a project to focus her scholarship and a way to present her research. Tinaye chose to focus on the economic impact of Carrollton’s cotton and hosiery mills on the city using Sanborns. Tinaye decided to focus her project on the Carrollton textile history because she was not very familiar with Carrollton. She noted that, “I am not from the west Georgia region, so this project exposed me to different cities that I had never been to and I was able to look into different years of each cities’ [history].” Her project research focused on Mandeville Mills, rehabilitated as the Mandeville Lofts, and presented about it at Scholar’s Day held at UWG. In her presentation, she analyzed the change in the American Textile Narrative as she examined the growth of Mandeville Mills during the 1920s, 1930s, and the 1940s. Tinaye said, “I wanted to show the change that America went through each decade, and how a mill in Carrollton could reflect the changes in America during each time.” The Sanborn maps assisted heavily with this research because it showed how textile industries grew and eventually declined throughout the twentieth century.

Sanborn maps allow for history to become a physical element. A city’s growth in industry, in size, and in city shape can be seen in Sanborn maps as the buildings shifted, opened and closed each year. Tinaye found out through that Sanborn maps that, “many cities did not just have cotton mills, but additionally had bleachery companies, machine shops, hosiery mills, knitting mills, and apparel manufacturing plants along with textile mills.” This allowed for a lot of comparisons to be made as well. Take Columbus, Georgia, for example. Tinaye spent significantly more time familiarizing herself with Columbus’s industrial history than some other places because there was just more industry there. The Sanborn map collection boasted thirtyish years’ worth of change and documentation in Columbus since the textile industry was prevalent for so many decades in Columbus.

Tinaye contributed to the Textile Heritage Trail heavily due to her research with the Sanborn Maps. Her study of the maps helped our team to better understand industry in the cities and allowed us to visually process all of the information and research that we had about the textile industry in Georgia. By analyzing the Sanborn maps, Tinaye could measure change in the cities over time, both yearly or in larger gaps, like she did at her presentation. This research helps us to understand the textile industry better, because it answers the questions of why, when, and where a certain building was built and for what purpose. That information is crucial to telling the history of the textile industry in Georgia, so that we can connect the places to the people who lived there.