Author: Greg Bell

When you join a project that has been going on as long as the Textile Heritage Trail, it can feel a little overwhelming. So many people’s energy and passion have gone into making this site what it is today, and at the beginning, I did not know exactly how to start getting involved myself. But when I was tasked with working with stakeholders this semester as part of our ongoing strategic planning, I knew this would be a great opportunity for me to really see how much this project means to people from all of our featured communities. As a result of the conversations I had this semester, I now feel like I’m right in the middle of the work being done. Our stakeholders’ passion is infectious, and their excitement about sharing what they are planning as well as ideas for how we at the Textile Heritage Trail can help them achieve their goals helped me understand how much the work we do here matters.

Working with stakeholders is an important part of any kind of public history project. Their input and expectations can be one of the most important elements that go into making a project succeed or fail. When I was first told that I would be responsible for speaking with our stakeholders this semester to find out what exactly they would like to see from the Textile Heritage trail going forward, I knew this was a major part of our strategic planning process. We had already been soliciting feedback from users on our website and had begun to make changes based on what we had heard, but this was going to be a completely different experience. I was admittedly nervous when I made my first phone call. What if I messed up a question, or misrepresented something one of my contacts asked? What if they didn’t want to talk to me?

As soon as I introduced myself, I realized that those were unwarranted fears. Our stakeholders were so excited to talk with me about what they were doing in their communities to interpret their textile histories and were eager to hear what ideas we had to support them. Everyone was kind and helpful, and almost immediately I began looking forward to making my calls. Altogether, I spoke with over 90 people who are involved in textile history, from librarians and museum professionals to city managers to tourism directors and chamber of commerce executives. They took place over the phone, over Zoom, and in a few cases through email. There was one of these conversations that were especially meaningful for me because I got to speak with the stakeholders in person.

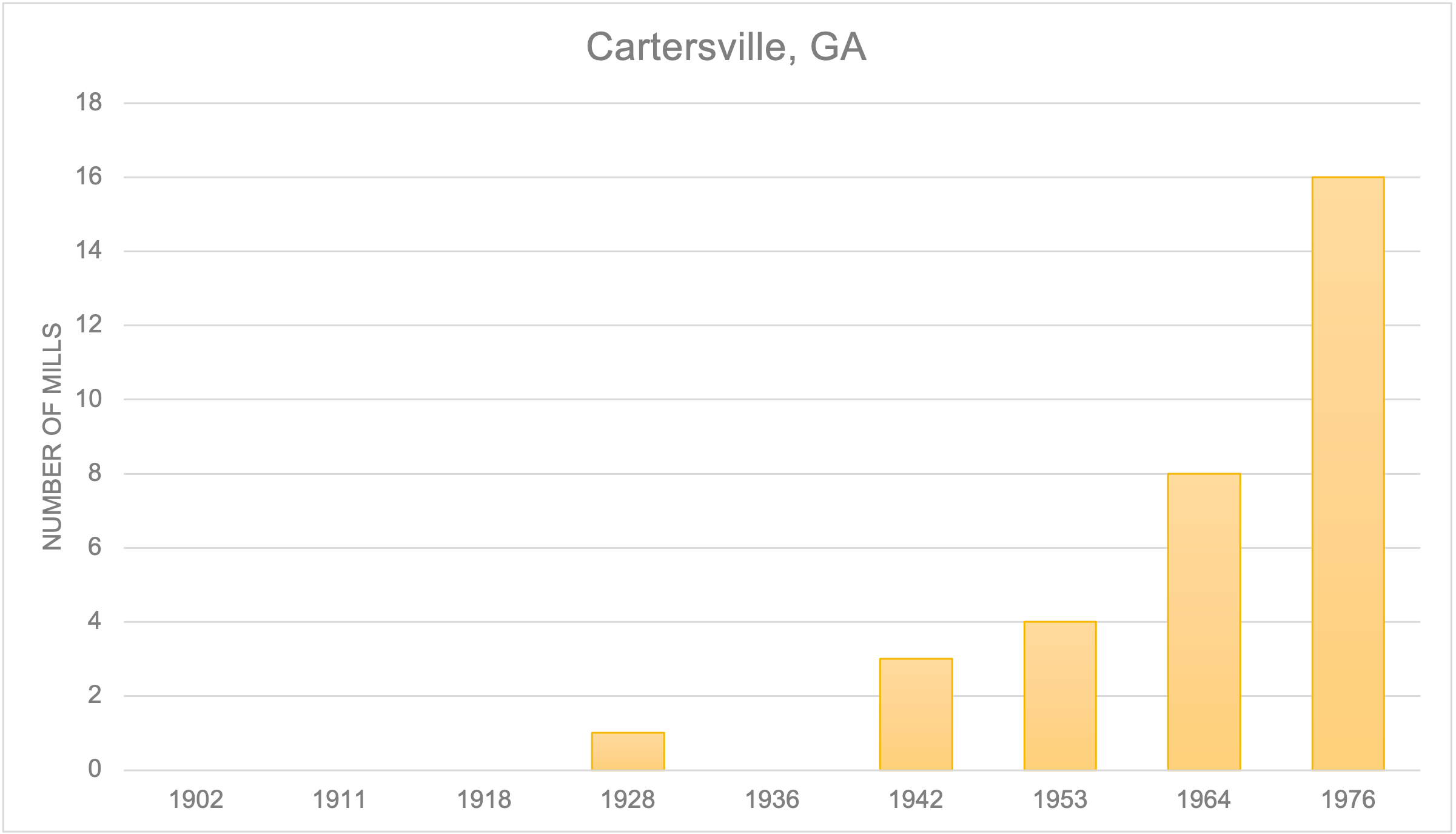

When I called Trey Gaines, the director of the Bartow History Museum, to set up a time to talk, I knew he would have a lot of meaningful input. Trey and I have known each other for a long time since I first interned at the museum while getting my bachelor’s degree. When he asked if I wanted to come and talk in person, I decided to make a day out of the trip. I arrived in Cartersville at 9:00 and met with Trey Gaines and Sandy Moore. We spoke at length about how the museum interprets the textile history of Bartow County, and I got wonderful feedback from Trey and Sandy about what we at the Trail could do to better support them in the future. As we were wrapping up, I asked what sites I should try to visit before I left Cartersville, and Trey and Sandy gave me directions to two of the old mill sites.

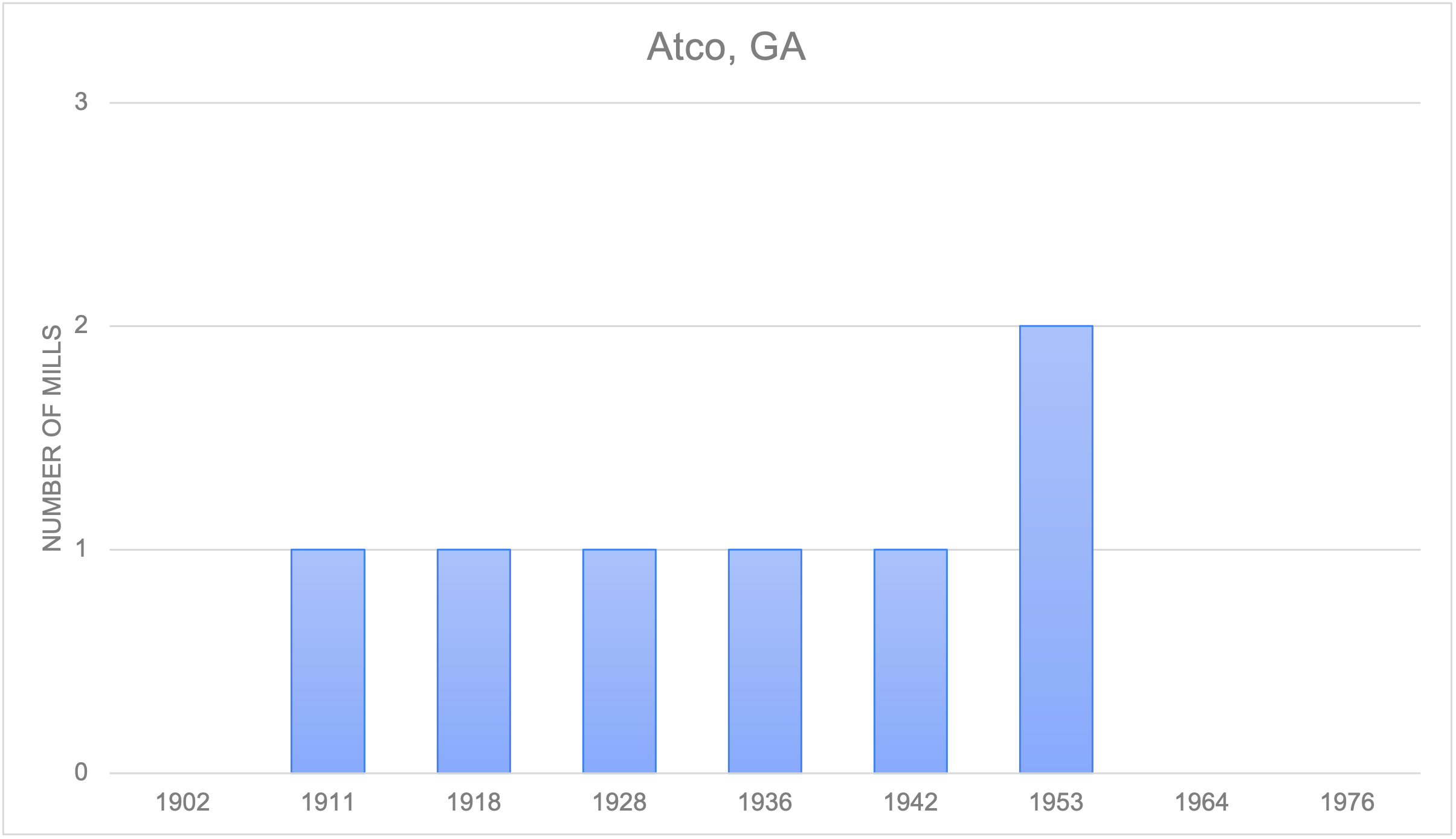

I left the Bartow History Museum and headed towards the first mill site Trey had told me about, ATCO & Goodyear. I arrived and looked around for a while, and then drove through the nearby mill village Sandy had told me about. The mill site itself is mostly gone, and the village’s homes are now just private residences, but being there in person I was able to picture what this site must’ve looked like while still operational. I then drove over the other mill site Trey had mentioned, the former E-Z Mill. Today, it is in operation as the Spring City Technology park, so I was not able to get an up-close look, but from the perimeter I could see the original building. Finally, before leaving town, I pulled up our Cartersville community page from the Textile Heritage Trail site, and used our StoryMap to navigate to other places of interest. It felt like I had stepped out of the role of textile history interpreter, and was instead just an enthusiast using our site for its intended purpose. From this point of view, I thought about the ideas I had discussed with Trey and Sandy, and I couldn’t help but get excited all over again.

As a result of the conversations like I had with Trey and Sandy, the Textile Heritage Team is planning on starting some exciting new work in the coming semesters. We’ve already made changes to our website, and new community pages are on their way soon. I’m grateful to be a part of the process and have enjoyed hearing the passion and joy other people have in interpreting these stories, because in the process it became my joy, too. I hope that as we continue in our strategic planning and determine what the Textile Heritage Trail will look like going forward, you are taken in by that passion too. I, for one, can’t wait to see what we do next.